Maureen Duffy at 80: In Times Like These

DUFFY AND KING'S

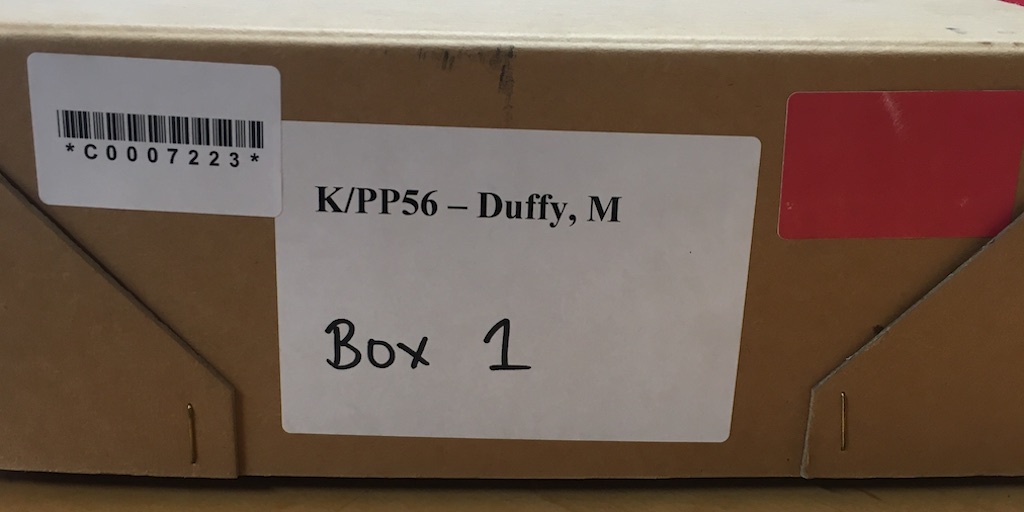

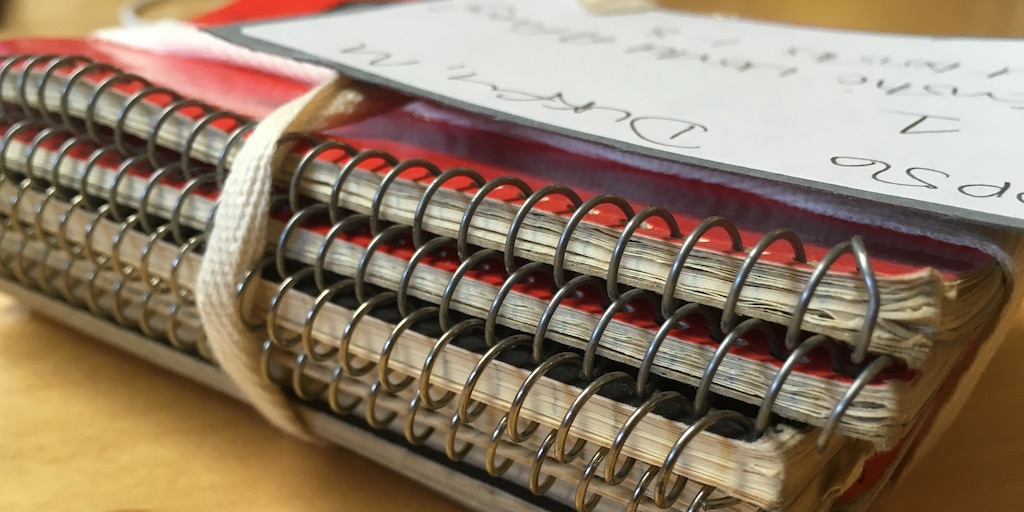

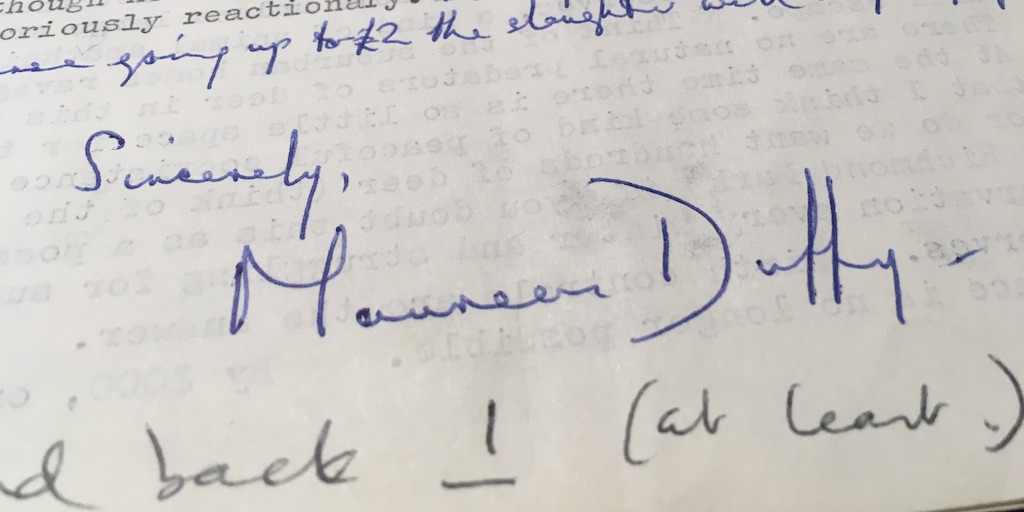

Header image: Maureen Duffy's notebooks, K/PP56, King's College London Archives.

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

by Clare A. Lees. With thanks to Katie Webb, Clare Brant, John Stokes and Max Saunders.

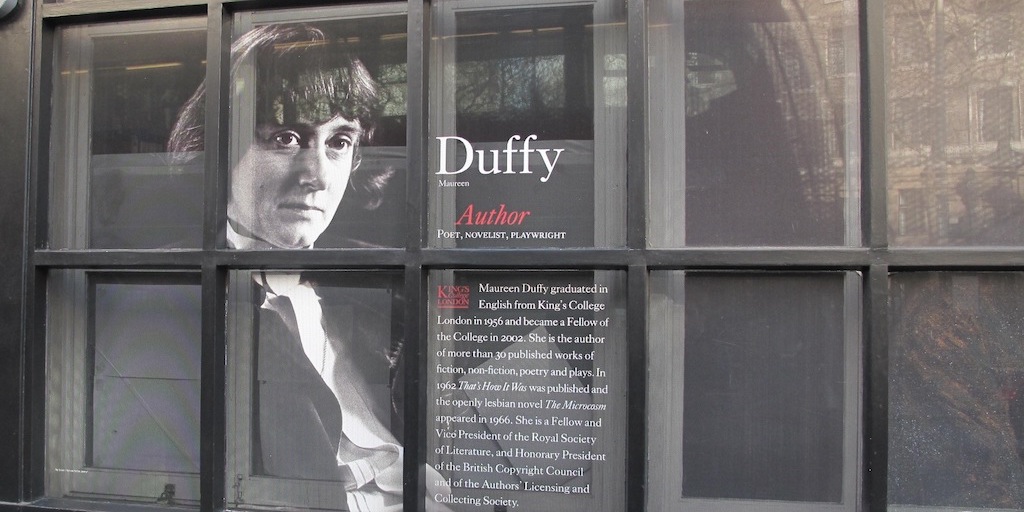

I confess that, as a member of King’s academic staff, I am absurdly delighted by the entry of King’s College London into twentieth-century fiction barely disguised, that is to say, not at all disguised, as Queen’s, London. One of Maureen Duffy’s most celebrated novels, Capital, published in 1975, part of her London trilogy (the other novels are Wounds of 1969 and Londoners of 1983), which is now finding its way back into print, albeit digitally.

It would be easy to dismiss this move, King’s as Queen’s, as a bit of queer undergraduate fun (save that the novel was published long after Maureen left King’s in the 1950s) or as the fictional revenge of a former student (save for the fact that Duffy’s most recent novels, The Orpheus Trail (2009) and the recently published In Times Like These (2013), like her earliest ones, are characterized by a robust gender politics and a deep engagement with the past, whether that past is literary or historical, as well).

For those unfamiliar with this trajectory, it may come as even more surprising that the medieval period has offered Maureen rich material too: The Orpheus Trail turns on the discovery of an early Anglo-Saxon royal burial; the earlier novel, Illuminations of 1991 tracks the travels of an eighth-century Anglo-Saxon nun, in Germany; In Times Like These looks to the earliest medieval period and the sixth century to contrast, presciently, the travels of the famous Saint Columba (or Colm Cille) across the pre-national kingdoms of Ireland, Scotland and England, with the post-national stories of these peoples now and in the future. Perhaps Maureen’s teachers at King’s in the 1950s taught her well (even if not enjoyably!). Indeed, I can think of few contemporary novelists that have inspired contemporary medieval scholarship, though the deeply fashionable literary journal, postmedieval, published a special issue on ‘medieval mobilities’ this summer, edited by two north American medievalists, Laurie Fink and Martin Schichtmann, which begins with a meditation on The Orpheus Trail’s fictional use of its medieval past.

Duffy’s interest in the different histories and cultures of these islands, in different genres – her work is characterized by its refusal to stick to one genre – surfaced early. I think of the ‘illegitimate’ working-class girl of the novel disguised as memoir, That’s How It Was (1962), for example, or of the otherwise ‘invisible’ stories of gay women in the city of The Microscosm of 1966 (long before Sex in the City!). Nor does Capital represent the culmination of Duffy’s interest in place and in London in particular. Her novels about the city, articulated using multiple temporal and psychological perspectives, are patterns of interest that have continued to characterise Duffy’s work long after the publication of Capital.

But Capital does represent a particular moment in the writing career of this novelist’s engagement with London and with the relationship of the present to its various pasts. This is a project pre-dating that of the better-known so-called psycho-geographers of London literature such as Ian Sinclair. And it anticipates too other, more recent London novels by, for example, Monica Ali (Brick Lane, 2003) and Zadie Smith (White Teeth, 2000, and NW, 2012). Duffy’s London fiction is influenced by that earlier modernist, Virginia Woolf of course, and her style has influenced in turn, I suspect, British women writers as different as Jeanette Winterson, Ali Smith and A. S. Byatt, whose projects are not always so much grounded in a particular place but share her determination to do the past differently.

Capital’s subject is London in that post-imperial decade of the 1970s, haunted by labour disputes, deflation, energy crises, wage disputes, as well as by class and gender experimentation and conflict. In 1975 Margaret Thatcher became leader of the Conservative Party, then in Opposition but soon to dominate British politics as the novel, published the same year, predicts with a certain prescience. (Thatcher was elected Prime Minister in 1979). The political mood of the contemporary city plays itself out in terms of an exploration of its past while also charting a relationship between an ageing porter and a middle-aged lecturer in the same dusty and jaded university college on the Strand (fictionalized as Queen’s – the doppelganger of King’s College London, if cities can have their doubles). Meepers, the porter, is an amateur archaeologist in search of an authentic account of the city’s origins after the withdrawal of the Romans from Britain – that most tricky historical period which has left behind so little written evidence. The anonymous lecturer is a specialist in 18th century history, teaching summer school while in something of a personal and professional crisis of his own (his lover appears to have fled to America).

In its engagement with the limitations of official history (figured in part by that century of reason, the eighteenth), its opening up to alternative histories (here figured by the amateur historian), and its quest narrative for the truth of the past we might want to think of Capital as a modern medieval romance (much as In Times like These calls itself a ‘fable’). It’s worth remembering that Seamus Heaney published ‘North’, his highly successful collection of poems that dig deep into northern mythologies to understand the contemporary politics of Northern Ireland in 1975; the same year as Duffy’s Capital. Both might be part of a critical awareness that the medieval has many different places even with the Atlantic archipelago of Britain and Ireland.

Interwoven with the contemporary narrative of the modern Capital, which is set over a few weeks in an unusually hot summer (one of several in the UK in the 1970s), is a sequence of discrete narratives from the city’s past. These begin with the earliest pre-history of what is anachronistically referred to as ‘London’ and ends with an apocalyptic description of a ruined, impoverished and over-populated city that seems to be one of its possible futures. The novel has much, often poignant, fun with these temporal irruptions of the not-yet into that which has already happened.

A Neanderthal stands ‘shivering in Whitehall’; a young ‘Artor’ (yes, that’s Arthur), after his ritual acknowledgement as leader in Heathrow(!), is bothered by the fact that no hand rises out of the lake into which he has thrown his sword; Death in the form of a flea runs through the capital in a personification allegory straight out of Piers Plowman; a transgendered King Elizabeth meditates grumpily on the need to go to Parliament and perform yet one more time; an old man called ‘Moloch’ indiscriminately dines on the heads of Germans and English soldiers in the Great War; and so forth.

Capital’s complex relation to historical fiction (Queen’s) as well as historical fact (King’s) often turns on these kinds of determined shifts of official history, literary or otherwise – of the kind that offers its readers King Elizabeth I – which insist on revealing those aspects of the past that would otherwise be unspoken by official history. Perhaps, then, the novel’s queer politics is better informed by that critical species of gender studies more familiar within academies like King’s well after the publication of Capital in the mid-1970s. After all, it was only in the early 1990s that King’s got its own, pioneering gender studies research centre: Queer@King’s. And it won’t do either to suggest that the official ‘second wave’ of feminism, so frequently dated to the 1970s – the moment of Capital itself – is any more helpful. The gender politics at work in Duffy’s London trilogy overall was a feature of her writing well before the late 1960s, reaching back to her first memoir, That’s How It Was of 1962, so its own relation to that official ‘second wave’ is similarly complex too. The challenge of Maureen’s work, in short, seems its refusal to stick in one particular time. Indeed, the novel begins ‘He couldn’t help it if the bones poked through the pavements under his feet’ (p.15), and its figures are haunted by the anxious burden of trying to excavate the past as much as they are by trying to understand each other.

A striking instance of how Capital does the past differently, anachronistically if you will, is its ‘Fragments from the Berkynge Chronicle, probably spurious’ (pp. 78-81). There is no Chronicle of the London abbey of Barking, of course, though many would wish there were. Bede in the early eighth century certainly knew of a house history for the Abbey, from which he culled his account in the Historia ecclesiastica. Duffy perhaps knew this in fashioning her own chronicle out of a translation and adaptation of a few entries from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle relevant to London’s history, 839-1018. These include excerpts from the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s account of Alfred’s Wars with the Danes, so beloved of generations of students who were taught Old English from Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader. In Capital in 851, for example, a fleet of ships sails up the Thames, in a style reminiscent of that of the Chronicle itself but with a touch of that irruption from a later time we have come to expect: ‘In this year, 350 ships came up the Thames and stormed Canterbury and London and then went South over Thames into Surrey and King Noblewolf fought against them and made the greatest slaughter of a heathen host we have heard tell of and he had possession of the place of slaughter’ (p. 78). This is more accurate than it first seems, as those of us who can still remember struggling to make sense of the phrase ‘held the place of slaughter’ (‘ahton wælstowe gewald’, Battle of Ashdown, line 8) already know. Some of it looks like pure fiction but is not. The King Noblewolf of the entry I just quoted is King Æthelwulf, for example, and thereby Duffy makes students of us all. Barking Abbey, to take another example, is founded by a woman called Noble Fortress! Æthelburh, as the rest of us like to call her. Anglo-Saxon names, with their buried compounds, take on a newly charmed life in this belated, very belated re-invention of the chronicle tradition. Capital, Duffy seems to argue, is a place where historical authenticity can meet literary invention and where the present as much as the past has possibility.

Sections and Chapters

Duffy and King's introduction

Katie Webb

Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives

Patricia Methven

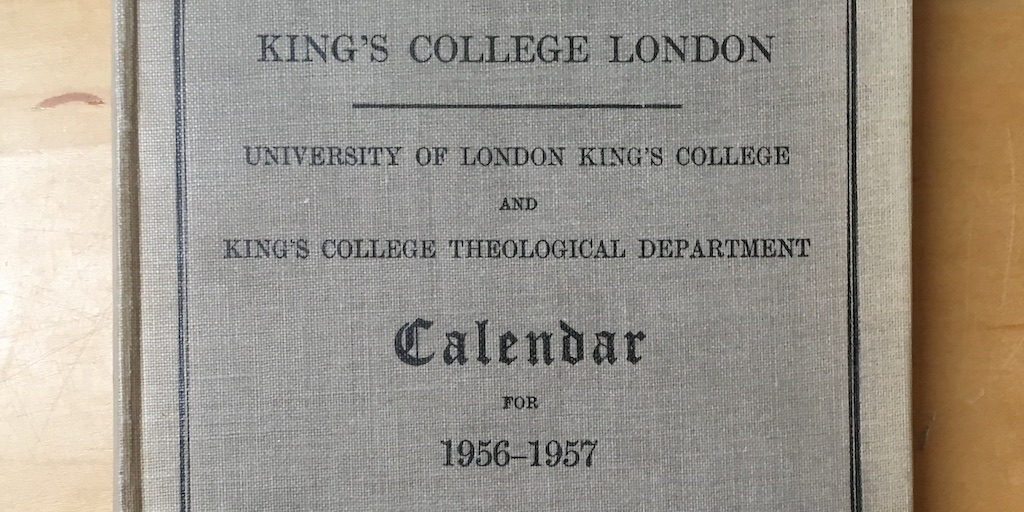

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

Christine Kenyon Jones

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

Clare A. Lees

Panel Summary: the city as a space for new possibilities

Phoebe Blatton

Writing, Rites, and Rights

John Stokes

A Window for Maureen Duffy

Clare Brant

Fighting and Writing introduction

Katie Webb

Duffy and the European Writers' Congress

Lore Schultz-Wild

An 80th Birthday Honorific Speech

Ingrid Protze

Memories of the German Writers' Union

Sabine Herholz

On Maureen

Katalin Budai

A copyright warrior and a true defender of rights

Olav Stokkmo

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy's contribution to gay rights and lesbian visibility

Jill Gardiner

For Maureen Duffy, Poiêtes

Karen Gevirtz

Editor's introduction

Katie Webb

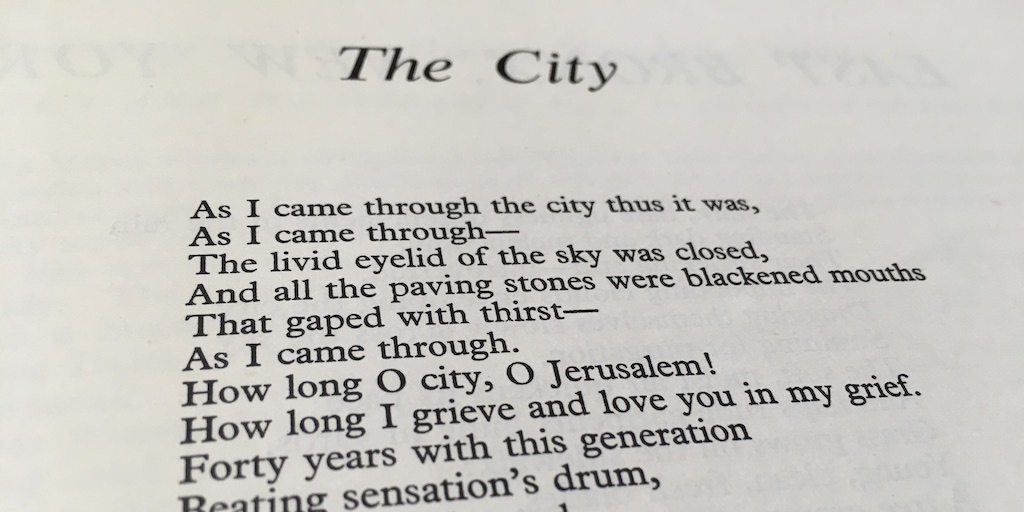

Maureen Duffy: Scrivener and Prophet

Charles Lock

Words that count: Maureen Duffy

Marina Warner

Browse articles on Duffy and King's