Robert Herrick’s Love Letter to London

Posted in 17th Century, Literature, Pre-1700, Strandlines, Thames and tagged with British history, Farewell London, London history, London memory, London writer, Poem for London, river thames, Sixteen hundreds

In 1629, Robert Herrick had to leave London to assume a post in Devonshire. Before his departure, he wrote His Tears to Thamesis to say his farewell to the city. It remarkably stands the test of time as an example of how one can feel deeply for their home. As an ex-pat of London, I empathise with his difficulty to say goodbye.

A little background

You are probably wondering, who is this Robert Herrick and how does he connect to the Strand? Fair questions, and I will get there eventually!

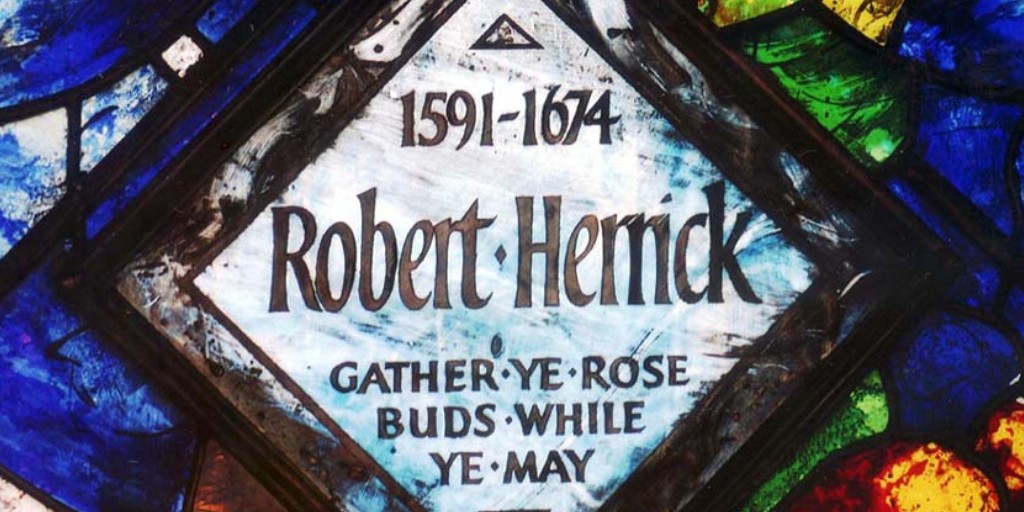

Rpbert Herrick, via The Dean and Chapter of Westminster.

First and foremost, Robert was the son of a certain Nicholas Herrick who died when the former was only a year old. William Herrick, Robert’s uncle, was “knighted for his services as goldsmith, jeweller, and moneylender to James I,” per Alfred W Pollard. Robert Herrick was apprenticed to his uncle for around ten years. We further know that he undertook a Bachelor (1617) and Masters (1620) at Trinity Hall, before becoming a cleric. Like many men of high education and class at the time, he was also a poet, moving in London literary circles and coteries. As for his departure from London, it seems that the King presented Robert to the Vicarage of Dean Prior in Devonshire. This displacement was described by Herrick himself as “irksome banishment” according to Geoffrey Hiller and his fellow editors.

A dreaded departure (1629)

Hiller and his co-authors claimed that “[Herrick] had a great fondness for London, its beauties, and the intellectual stimulus his literary companions provided.” Herrick’s departure loomed and he expressed his anguish in the form of a poem, His Tears to Thamesis. This is truly a love letter to the city of London, as he knew it. Importantly, it also provides inklings as to what his life consisted of in London. As such, it has great value. The reader can feel the emotions portrayed by Herrick as well as gain a better understanding of London in the 17th century. Once again literature provides a great basis for understanding history!

Strand spotted!

“I send, I send here my supremest kiss

To thee my silver-footed Thamesis. [the Thames]

No more shall I reiterate thy Strand,

Whereon so many stately structures stand;

Nor in the summer’s sweeter evenings go

To bathe in thee, as thousand others do.”

Here you can see Herrick’s link to our beloved Strand. In his poem he pays particular respects to the Thames (or Thamesis), and such mentions the Strand. In this context, the use of “Strand” seems almost in duality between our modern understanding and the old English sense, the shore of the Thames. For more details on this etymological evolution, I encourage you to read Tea Emily Carter’s piece! He mentions ‘reiterating’ the Strand. By this he means to walk up and down the shore, a feeling anyone who has explored central London will know well.

Moving further down, the mention of “stately structures” on the Strand reinforces the idea of the street’s importance historically. If the stately buildings of the 1620s impressed Herrick, I can only imagine how he would view the important venues on the Strand currently! Lastly, the longing to bathe in the Thames in the summer time is not a sentiment I can say I share… It does, however, point to a long-lost norm in London life. This is fascinating and reveals another piece of the puzzle concerning Herrick’s life day-to-day.

Itinerary of interest

“No more shall I along thy crystal glide

In barge with boughs and rushes beautified,

With soft-smooth virgins (for our chaste disport)

To Richmond, Kingston, and to Hampton Court.”

While his comments on “soft-smooth virgins” raises eyebrows, Alfred W Pollard believes it is a reference to “his courtier-life in London”. This analysis offers us another peek through the looking-glass, so to speak, as we piece together Herrick’s privileged life in London. Lastly, the line “to Richmond, Kingston and to Hampton Court” gives us a good idea of the places Herrick visited. We must note that these are largely areas of west London, even considered to be outside London at the time. Pollards goes on to mention, “Dr. Grosart even presses the mention of Richmond, Kingston, and Hampton Court to support a conjecture that Herrick may have travelled up and down to school from Hampton.” This may be true, and also may be misinformed as we will address below.

Herrick’s heritage

“Never again shall I with finny oar

Put from, or draw unto the faithful shore;

And landing here, or safely landing there,

Make way to my beloved Westminster,

Or to the golden Cheapside, where the earth

Of Julia Herrick gave to me my birth.”

In the first couple lines, Herrick reminisces about rowing on the Thames from place to place. Yet, the places themselves are of note. When Herrick mentions “my beloved Westminster” it is thought to refer to Westminster school, where he may have been educated. As for “the golden Cheapside” where he describes his birth to Julia Herrick, his mother, it is historically the goldsmith’s district per Hiller. This is important information seeing as we know Herrick stayed around ten years with his uncle as an apprentice goldsmith. Hence, the idea that Herrick came from Hampton to go to school (likely in Westminster) whilst his uncle (and legal guardian) presumably worked in Cheapside seems dubious. This is the beauty of looking into persons from this period! Piecing together tangible information to recreate history is incredibly compelling. In that vein of decoding information, Hiller et al. point to the mention of “Julia Herrick” and “earth” in juxtaposition as crucial seeing as “Herrick’s mother died shortly before he left for Devon [1629] hence the mentioning of the earth of her grave”.

A Final farewell

“May all clean nymphs and curious water dames,

With swan-like state, float up and down thy streams;

No drought upon thy wanton waters fall

To make them lean and languishing at all.

No ruffling winds come hither to disease

Thy pure and silver-wristed Naiades.

Keep up your state, ye streams; and as ye spring,

Never make sick your banks by surfeiting.

Grow young with tides, and though I see ye never,

Receive this vow: “so fare-ye-well forever”

Herrick’s final section is full of mythological references, making London seem almost ethereal. Nymphs, water dames, and silver-wristed Naiades make up the population of this Olympus-like river which flows through our city. This reverence is unending it seems as Herrick confirms “never make sick your banks by surfeiting”. He surmises that he can never lose his love for this river and, presumably, this town. In the final lines, he bids adieu to this wondrous waterway. Fare-ye-well forever he exclaims. Such ends this poem full of love, longing, and personal history.

“On your banks I will stand anew…”

Being a Londoner living abroad, I can see myself in this glorified literary version of London. I miss the metropolis I grew up in, full of stately buildings, picturesque parks, an unending river and, of course, the Strand. Herrick does an excellent job and portraying both elements of his life and his love for London within a short poem. The fact that this poem remains intriguing almost 400 years later is a testament to the eternal city that is London. Now, a short and sweet stanza in Herrick’s style.

On your banks I will stand anew,

Shared moments we have a few,

Tides shifting by the Strand,

Near the buildings I will stand,

Until then I bid you farwell,

Across the pond I shall dwell.

I admit it’s not revolutionary literature, nor is poetry my forte. Yet I find Herrick’s piece a comforting reminder that London will be waiting for me when I can go back. Hope you enjoyed Herrick’s poetry as much as I did!

Sources

An Anthology of London in Literature, 1558-1914 – by Hiller, Geoffrey G., Groves, Peter L., Dilnot

The Hesperides & Noble Numbers– by Robert Herrick (Edited by Alfred Pollard with a preface by A.C. Swinburne)

The Olympians by The Olympians (Album I listened to while writing this article and worth a listen)