Dracula Stalks the Strand

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, entertainment, Literature, Strandlines, theatres, Theatrical and tagged with Burleigh Street, dracula, theatre

On the back wall of the Lyceum theatre in Burleigh Street are three engraved names: Stoker, Irving and Terry. They honour three great characters of the British theatrical world in the late 19th century.

The Burleigh Street side of the Lyceum Theatre. ‘Terry’, ‘Stoker’, ‘Irving’, can be seen carved into the wall.

Henry Irving was the actor/manager of the Lyceum from 1878 to 1902. Ellen Terry was one the most famous actors of her age, who performed with Irving and in his productions as leading lady from 1878. However, the least applauded of the trio, whose official job description was simply Acting Manager, is the man whose name has greater global resonance today.

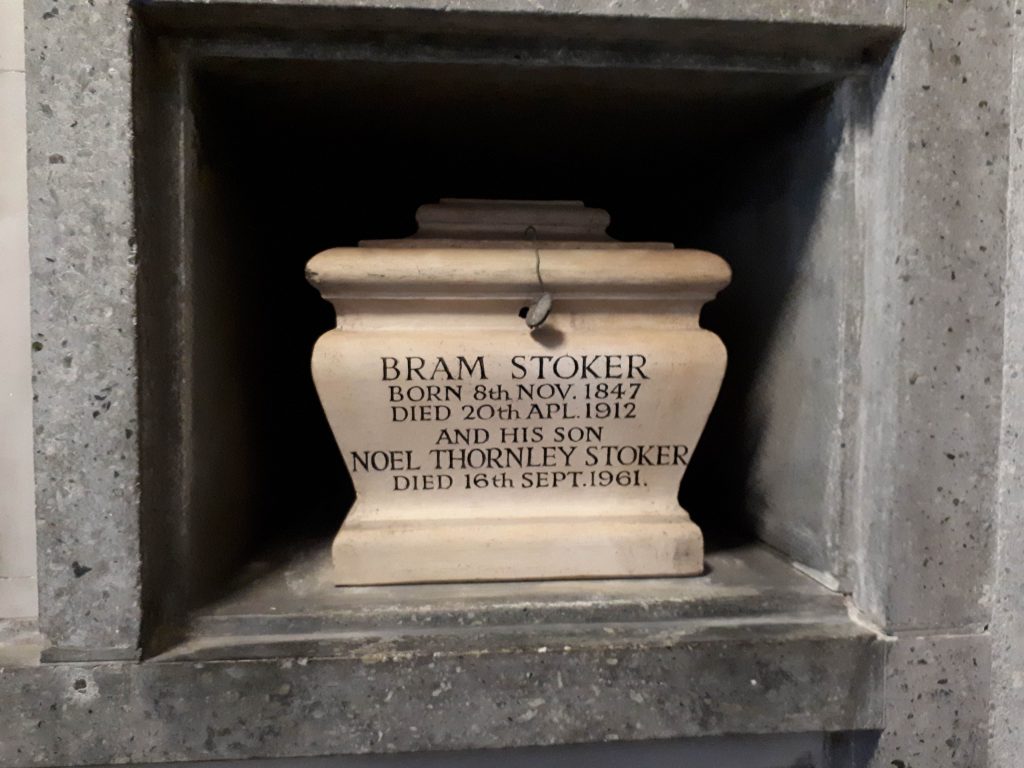

Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, worked for Henry Irving from 1878. He was not merely Irving’s right-hand man, but his friend, travelling with him until the great man’s death on tour in 1904 in the foyer of his hotel in Bradford, following his performance in Tennyson’s Becket. Stoker named his only child in honour of Irving, who was godfather to Noel Irving Stoker. Yet despite this intensely close professional and personal relationship, Irving left Stoker no legacy, and the author of the most famous vampire novel died after months of illness and anxiety about his income.

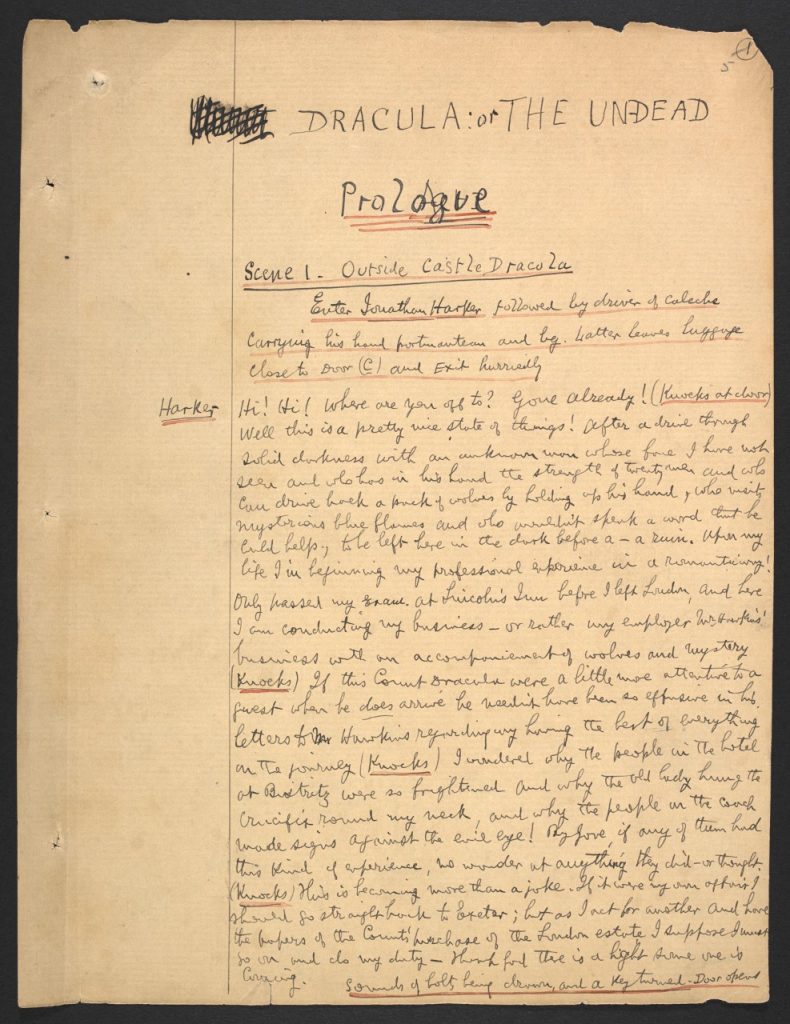

Opening scene from the manuscript of the Dracula playscript, in the British Library.

The connection between the three names is perhaps most clearly evident in the dramatic reading of ‘Dracula or The Undead’ on 18th May, 1897 – eight days prior to the novel’s publication. This took place at the Lyceum theatre and was performed by the theatre’s resident company. The purpose of the reading was to ensure Stoker would retain copyright over the plot and characters of his novel if it were ever to be used on stage; it could not have been intended as a rehearsal of an authentic stage adaptation, as the ‘script’ was 40 scenes long. It is estimated that it would have taken between 4 and a half to 6 hours to read.

There were only 2 paying audience members for ‘Dracula or The Undead’, as following the typical practice for a copyright reading, playbills were posted on 30 minutes before the performance, and even a committed theatre-goer would have needed to be in the right place to spot the advertisement. The expense of one guinea for admission might also have kept the crowds away. To modern eyes the most famous member of the cast would have been Edith Craig, the daughter of Ellen Terry.

Surprisingly, the Lord Chamberlain approved the play, despite the overtly sexual behaviour of the various vampires. He wrote personally to Stoker to say that he had found ‘nothing unlicensable in this very remarkable dramatic version of your forthcoming novel.’

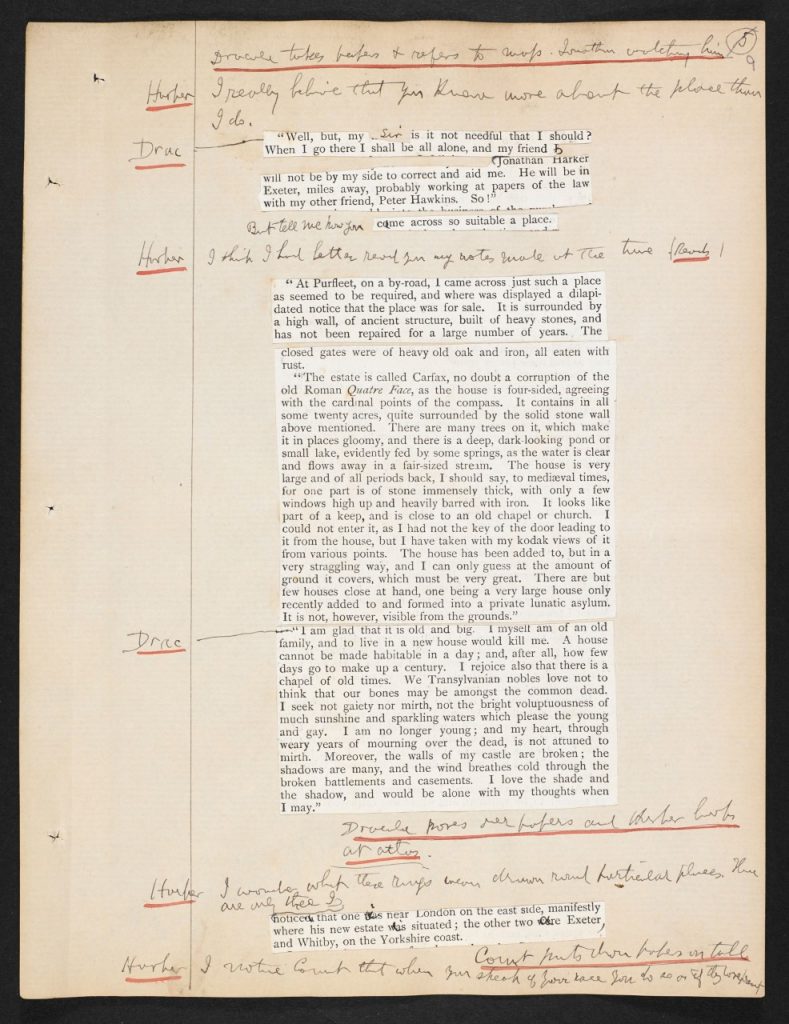

Further page from the manuscript held at the British Library, showing Stoker’s handwritten script alongside sections cut and pasted directly from his novel. As the script progresses there are more of these showing his reluctance to rewrite the text, as it is purely for copyright purposes.

There’s a common misconception that Henry Irving – tall, dark, gaunt – could have been the role model for Dracula. Perhaps there was something in Irving’s demeanour that inspired Stoker’s physical depiction of the Count; they are both characters who enjoy presenting disguised versions of themselves. But this comparison doesn’t really have legs: literary vampires before Stoker’s Count were often presented as charming, aristocratic and Eastern European (for instance, Polidori’s Vampyre Lord Ruthven and Le Fanu’s Carmilla).

Despite the speculation that Stoker would have liked Irving to take the part, Irving allegedly called it ‘dreadful!’: probably due to the length of task and the clunky nature of the script. But why else might Irving have been so averse to the dramatisation?

A superficial analysis of the novel suggests overlaps that could have been attractive to the actor – the theme of disguise, a nobleman of foreign birth and mysterious, romantic background, the confrontation between good and evil. It is however, one of the most striking features of the novel that the eponymous villain has the least to say. He is at his most terrifying in a few brief, lurid encounters. Irving would have found the part unappealing and melodramatic; his preference was for more psychologically challenging characters.

Perhaps by the 1890s Irving had lost his touch in the choice of parts that drew audiences. He turned down Conan-Doyle’s offer to take the role of Sherlock Holmes, yet another of the characters gripping the public’s imagination in the 1890s. He was certainly making odd financial decisions and needed to fund the theatre by frequent tours of the provinces and America, reprising much-loved roles.

Ellen Terry played a major part in the success of the Lyceum company from her arrival in 1878. She played some of Shakespeare’s great heroines – Ophelia, Viola, Beatrice, Juliet and Portia, her last role with the company in 1902 – to great acclaim. However, Terry had her eye on new dramatists, and when Irving brought his management of the Lyceum to an end that year, she went on to found a new company producing the works of Shaw and Ibsen among others. Terry’s company succumbed to financial difficulties and on Irving’s death, she retired in distress from the stage. It was she who claimed that they had been lovers. Nonetheless, she returned to theatre the next year, performing on stage and on film until 1922. This grande dame of British theatre died in 1928.

The golden years of Irving’s Lyceum company seemed to close coincidentally with the publication of Dracula; he faced competition from new theatres, new forms of theatre (such as music hall) and even from the embryonic film industry. Irving lacked the resources and perhaps the energy to take these on.

The urn containing Bram Stoker’s ashes, and those of his son, in Golders Green Crematorium. His wife’s ashes were scattered elsewhere in the same crematorium.

After years of making losses, Irving sold the business in 1902. When Irving died in Bradford, Stoker was left without a theatrical career, or perhaps could not find the passion to work with anyone other than Irving. Stoker became reliant on his grants as well as his writing to supplement his income. While his memoirs of his former friend (Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving) brought him some notice, it was not a consistent income stream. He wrote a good number of novels and short stories in his final years, yet none achieved the impact of Dracula. In the year before his death he published The Lair of the White Worm, but he knew it would be his last. It achieved no critical acclaim.

Ironically, it would be years after Stoker’s death that his novel would begin to see its full financial and dramatic power developed. His widow’s attempts to have F. W. Murnau’s illicit German version ‘Nosferatu’ destroyed would be futile, leaving the world with the grotesque image of Max Shrek’s Count Orlok as the first visualisation of the vampire.

Excellent article, thank you.

Thank you for reading!

– Fran, assistant editor

Dreadful. I believe Irving meant it in the old fashioned sense as ‘frightening’, not ‘bad’. Irving loved the macabre and he would have had the intelligence to understand the ‘reading’ for what it was and not its artistic merit.

It is fashionable to cast Irving as a despotic taskmaster, belittling Stoker and others but on the evidence of my own research find he was anything but. Dedicated to his art yes.

Hi Silvia,

That’s an interesting interpretation. Would you consider the term Penny Dreadful as an example that would back your position?

On the other hand, Irving has not been cast in the way you mention. In fact he is called a ‘great man’ in the third paragraph.

You seem to care for Irving’s story, would you be open to expanding more on it?

Thank you for reading!

– Tristan, editor

Great article, thank you! I was the creator of this memorial to the trio of Irving, Stoker and Terry on the new rear stage wall of the reconstructed Lyceum Theatre stage which (re)opened 25 years ago this month:

https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/rock-opera-jesus-christ-superstar-lyceum-theatre-london-1353449.html