Some Literary Testimonies on the Strand

Posted in Strandlines and tagged with account, diary, eyewitness, lifewriting, Literary London, London history, London life, memoire, My Strand, strand

Through centuries and countries, the Strand has always inspired awe and exalted writers. Through the different testimonies collected in this short article emerges the feeling that the Strand stands unique in the imagery of London. It exerts a fascination – be it sensory, musical, political, economic – to all visitors; insiders develop memories of it, outsiders draw comparisons. In all of these views, the Strand seems to shine among the other neighbouring streets.

– Giordano Bruno –

Giordano Bruno,

Ash Wednesday Supper (La Cena delle Ceneri), via Dartmouth.

The Italian polymath and friar Giordano Bruno spent a couple of years in England, frequenting the intellectual circles and publishing many important and controversial treaties during his stay. The most notable, the Ash Wednesday Supper (La Cena delle Ceneri), was written in 1584 while Bruno was in London. He was hosted by his friend Michel de Castelnau (1520-1592), ambassador to Elizabeth, at the French Embassy which was then located off the Strand, on Butcher Row (which does not exist anymore, it was stood roughly between Aldwych and St Clement Danes, partly on the path of the present-day Strand).

Bruno describes in the second dialogue the difficulties he and his guests face trying to reach another house [1]:

“Although we were on the straight road, we thought to do better by making a shortcut; we turned to the river Thames to find a boat going toward the Royal Palace.”

Here Bruno describes the Strand as “the straight road”, and Whitehall as “the Royal Palace”. The Strand was notoriously muddy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; using the Thames as a shortcut was a common solution, hence the many (mostly now lost) watergates on the riverside.

Bruno continues to describe the journey:

“We reached the embankment of the palace of Milord Beuckhurst,

These watergates often served as the first view of a nobleman’s palace; hence they often aimed at an impression of power, yet great taste.”

Lord Beuckhurst, aka Thomas Sackville (1536-1608) was known for his literary and political influence in intellectual circles. His palace, which stood on today’s Carpenter Street, was better known as Salisbury House.

“and there, shouting and calling boatsmen, we wasted as much time as we would have been enough to walk at leisure to the appointed place [Sir Fulke Greville’s mansion] and even to do a little business.

Finally, two boatsmen replied from a distance, and little by little they came, as if they were risking their lives, to touch the bank […]

They unloaded us there, and after paying them and thanking them; they showed us the straight path to get to the street.”

The street that Bruno is describing is a now a lost alley connecting Temple Place to the Strand.

“[…] In conclusion, tandem leata arva tenemus [we have reached, at long last the happy fields]. We feel that we were in the Elysian fields by having arrived at the wide, regular street. And from there, judging by the appearance of the site where this damned detour led us, lo, we found ourselves little more or less than twenty-two steps away from the spot where we started out to find the boatsmen, and near the lodging of the Nolan.”

Bruno and his friends now stand on the Western end of Butcher’s Row.

“When we were at the pyramid near the Palace in the middle of three streets, there came from the opposite direction six noblemen, who had a pageboy in front with a lantern, and of these one gives me a jolt, which, by turning me around, made me see another, who gave the Nolan a double jolt so gentle and robust that it could have passed for ten.”

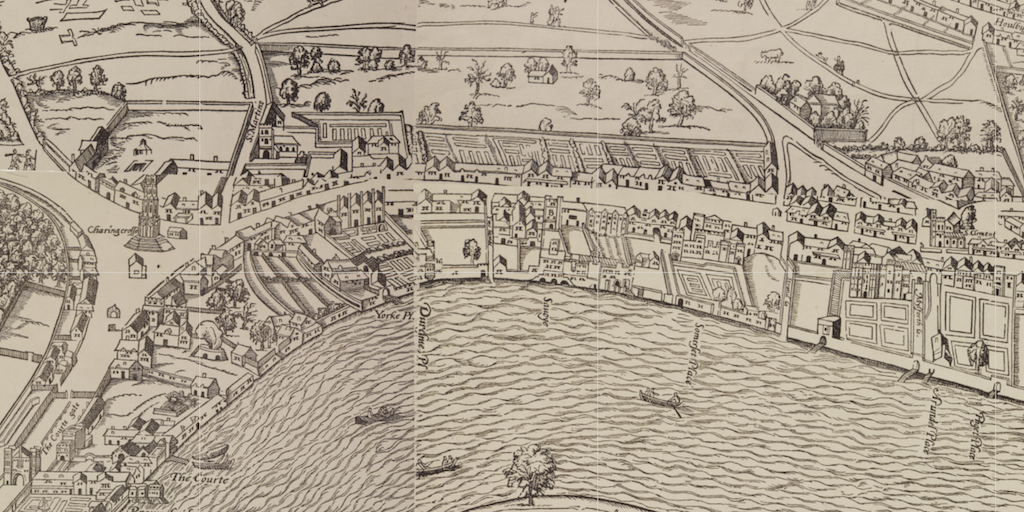

Charing Cross on the 16th-century Agas Map, via Layers of London.

Here the party are assaulted by a group of nobles next to Charing Cross, close to the pyramid – which refers to the old Eleanor Cross – at its old location, closer to the Palace at Whitehall than it is today. (The cross would be destroyed in the seventeenth century and rebuilt at the end of the nineteenth century in front of Charing Cross Station and Hotel).

Bruno concludes his humorous description of the perils he faced with:

“This was the last squall. Because a little beyond, thanks to St. Fortunis [St. Fortunatus of Aquileia, martyr of Diocletian persecution] after having covered such badly trodden paths, passed so many doubtful detours, forded so many rapid rivers, traversed such sandy beaches, overcome such mudholes, cut across such turbid puddles, trod through such strong torrents, lived through such rude encounters, crossed such slippery streets, stumbled on such ragged rocks, cast upon such dangerous reefs, we reached alive, by heaven’s grave, the port, id est the gate, which as soon as we knocked on it, was opened.

[…] We go insinde, go upstairs, and find that after having waited for us for so long a time, they desperately sat at the table.”

Giordano Bruno ends his second dialogue by introducing the retelling of conversations he had with London’s intellectual circles at Sir Fulke Greville’s place that he describes in later dialogues:

“While the historical sense is being sifted, tasted, and masticated, there will be submitted propositions, some topographical, others geographical, some rational, others moral.

Also speculations, some of which are metaphysical, others mathematical, other physical.”

One can see in these short excerpts how a major thinker of the Renaissance introduces in one of his important (paradigm-shifting) books, a playful description of the Strand, and notice how much it already was in the sixteenth century a central part of London’s life and imaginary.

– Stendhal –

A pioneer of French realism in literature — even dubbed “France’s last great psychologist” by Nietzsche for his ability to capture the mind of a character — Stendhal (born Marie-Henri Beyle) was also a ferocious traveler and art lover.

While his name remains attached to Northern Italy which he explored to great length, he also travelled briefly to London in August 1817. His thoughts on the city, and particularly the Strand where he resided, are recorded in his diaries. The following lines have been gawkily translated from French by myself, based on the text in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade 1981 edition of his Œuvres Intimes (Vol I) [2].

“From St. Paul’s, we found the Strand much superior to the rue Saint-Honoré [at the time, a major commercial street in Paris]. The protruding sundial was very handy.

The street [Strand] is twice as wide and the shops are almost as pretty as the nicest ones in the rue Vivienne [idem.]. Luxurious watches and showcases. Several boutiques are much prettier than any in France.”

[…]

“We found ourselves to be enjoying London the most by strolling in the streets.”

[…]

“An Englishman, hoping to initiate contact — a most peculiar thing in the English temperament — showed us to Mr. Coops (sic), a famous banker who introduced himself as being seventy-five years old and seventy-two millions worth.”

Thomas Coutts via wikimedia.

Here, Stendhal actually refers to Mr. Coutts, the founder of Coutts & Co., whose headquarters is still on the Strand today. Coutts, born in 1735, would have actually been 82 at the time of the meeting.

Stendhal recalls another meeting with a businessman on the Strand:

“Visited Mr. Macklin. Despite being located in the middle of the city, on the Strand, and close to Somerset House, the view on the Thames has a remarkably rural feeling. We frequently see sailing boats rapidly crossing Waterloo Bridge to our left.

There, we met Mr. Barker, the panorama maker.”

By looking in Kent’s 1818 London directory [3], it is possible to find the exact address from where Stendhal observes the Thames. Indeed, a certain W. H. Macklin, feather and flower manufacturer, is listed as living at 1, Strand Lane. Today, the building is incorporated within King’s College Campus, Strand Lane. However, the building used to be residential, as shown by the elements of still-standing Georgian housing that can be seen among the other College buildings. The view upon Waterloo Bridge had not yet been blocked by the 1831 extension to Somerset House, built by Robert Smirke for King’s College.

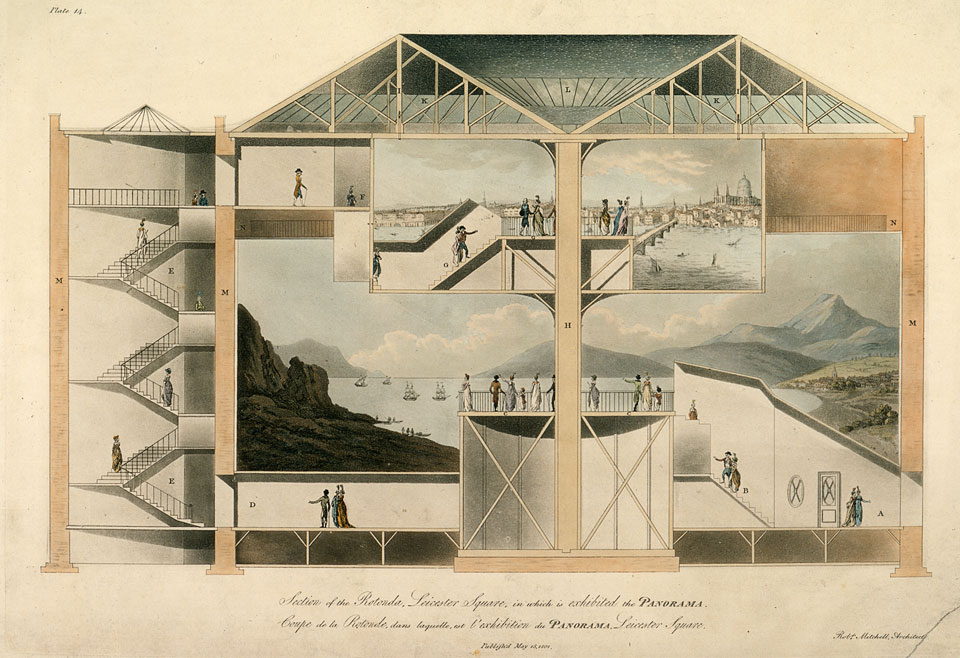

Cross-section of Barker’s Leicester Square Panorama (1801) via wikimedia.

The “Mr Barker” that Stendhal here refers to Henri Aston Barker (1774-1856), owner of the Leicester Square Panorama; famous for his grand exotic and military scenes. The French visitor will go and admire Barker’s Waterloo panorama a few days later; it was Baker’s most lucrative exhibition.

Stendhal recounts a further cultural encounter:

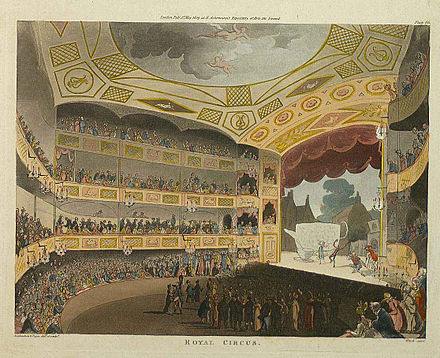

“Visited Surrey Theatre. The theatre is very cool, and the orchestra very good. The execution of the Dom Juan overture was excellent. However the pianoforte had to be played continuously — otherwise the great theatres of Drury Lane and Covent Garden could sue.

We talk with a tall thin Englishman, who finds London inferior to Paris when it comes to entertainment.”

This episode relates to the patent theatre monopoly in place at the time. Since the 1660 Restoration, only two theatres in London were allowed to perform “serious” drama, ie. “spoken” plays; as Stendhal notes, these were the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, and Theatre Royal in Covent Garden. Other theatres had to punctuate plays with music or dance moments. The continuous piano that Stendhal comments upon was a way to bypass legal restrictions during the performance of plays of all kind. This legal arrangement was revoked in 1843.

Travelling around London, especially along and on the Thames, is important in Stendhal’s narrative, with such moments prompting time for reflection:

“We walk past Black Friar (sic) Bridge. Edouard tells us that Strand Bridge cost four times more.

The Londoners do not really like the name of Waterloo Bridge and persist in calling it Strand Bridge. The military spirit is not seen as glory’s only custodian.”

The last sentence can be interpreted as a bitter comment on France after the fall of Napoleon in 1815. Stendhal had had a complex view on the French Empire, a combination of admiration and disillusion.

– Charles Dickens –

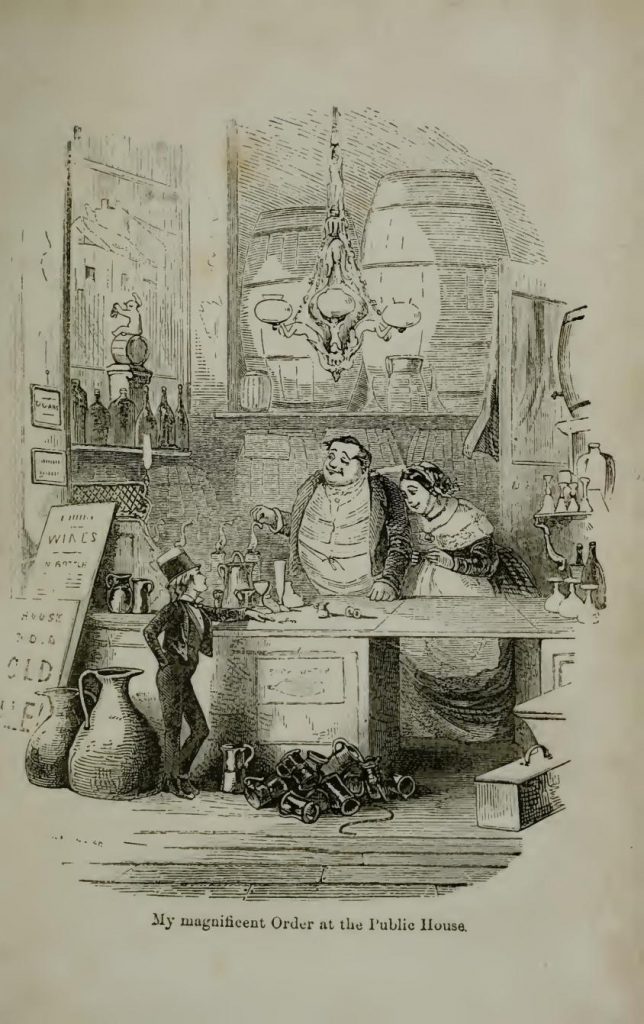

Food is extremely important throughout David Copperfield. ‘My magnificent order at a public house’, via Project Gutenburg.

In two passages from David Copperfield (Chapter 11), Charles Dickens obviously reminisces his own early years through a sensory description of the food around the Strand.

“I remember two pudding-shops, between which I was divided, according to my finances.

One was in St. Martin’s Church {1} — at the back of the church — which is now removed together. The pudding at that shop was made of currants, and was rather a special pudding, but was dear, two-pennyworth not being larger than a pennyworth of more ordinary pudding.

A good shop for the latter was in the Strand — somewhere in that part which has been rebuilt since {2}. It was a stout pale pudding, heavy and flabby, and with great flat raisins in it, stuck in whole at wide distances apart.

[…]

Once, I remember carrying my own bread (which I had brought from home in the morning) under my arm, wrapped in a piece of paper, like a book, and going to a famous alamode beef-house near Drury Lane, and ordering a ‘small plate’ of that delicacy to eat with it. What the waiter thought of such a strange little apparition coming in all alone, I don’t know; but I can see him now, staring at me as I ate my dinner, and bringing up the other waiter to look. I gave him a halfpenny for himself, and I wish he hadn’t taken it.”

{1} St. Martin-in-the-Fields on Charing Cross Road.

{2} Likely to be around today’s Wellington Street, which was reshaped in 1833-5, ie. after the years in which this memory takes place.

Dickens’s musings on choosing where to eat based on his budget may very well ring familiar to people who live and work on the Strand today. How much busier (well, pre lockdown at least…) is Gordon’s Wine Bar the Friday after pay day, compared to any other day! His descriptions also show how much has changed even in the small details of life: who today would describe a delicious pudding as “flabby”. What foods or drinks will define the Strand in years to come?

– Andrea Trevisan –

And finally, let’s examine the writings of a traveller whose link with the Strand is slightly looser. Andrea Trevisan was a Venitian nobleman, appointed ambassador to the King of England in 1498. He stayed for some months in London, where he would develop good terms with Henry VII, report on the latter’s friendly relations with Venice, and negotiate the state of taxes on wine from Italy. He left England in April 1498, after receiving a 500 ducats collar, a horse, and a knighthood in Westminster.

In frequent letters, Trevisan described many details of his stay in the English capital [4]:

“Although this city has no buildings in the Italian style, but of timber or brick like the French, the Londoners live comfortably and, it appears to me, that there are not few[er] inhabitants than at Florence or Rome.”

Indeed the Renaissance of English Architecture (that is, its return to antique principles) was quite late, especially in domestic architecture. Medieval styles were favoured up until the middle of the sixteenth century, when prodigy houses progressively started to incorporate Classical features. But even then, the ornamental vocabulary is closer to the Mannerist Renaissance of France or Flanders than the restrain of Italy — see for example Burghley House, Cambridgeshire.

As Trevisan was writing his letters, building in brick was a relatively new trend, started under the reign of Henry VI. The majority of houses in London were, for reasons of cost, timbered; this remained the case until the Great Fire, after which timber exteriors were forbidden.

The true adoption of Italian taste in architecture started in the 1630s, with the completion of Queen’s House, Greenwich. Its architect, Inigo Jones (1572-1652), is widely considered to be responsible for the change of British taste towards Andrea Palladio’s principles and both kept strong influences up until the Victorian era (see, on this, the entires for the York Watergate and the Adelphi on the Strand).

Despite the architecture not quite being to Trevisan’s tastes, he is taken with London:

“It abounds with every article of luxury, as well as with the necessities of life: but the most remarkable think in London is the wonderful quantity of around silver. […]

In one single street, named the Strand, leading to St. Paul’s [understand: the old medieval St. Paul’s] there are 52 goldsmith’s shops, so rich and full of silver vessels, great and small, that in all the shops in Milan, Rome, Venice, and Florence put together, I do not think there would be found so many of the magnificence that are to be seen in London.”

On first reading, we might celebrate the Strand getting such praise!

However, mention of the Strand here is quite dubious. Despite being an important commercial way, the Strand has never been renowned for its gold- and silversmiths. Cheapside (from the Old English ‘ceap’ meaning market place), however, was; its high concentration of very skilful craftsmen gave it the name of “Goldsmiths’ Row”. It is also leads directly to St. Paul’s, whereas the Strand (Stronde) is simply in the alignment of Fleet St. (Flete Strete) and Ludgate Hill (Bower Rowe); two long and narrow lanes in the sixteenth century.

I suspect the discrepancy might have come from the translation: Andrea Trevisan gives “… una strada sola, che si chiama la Strada, che va à San Paolo” which the Camden Society wrongly translated in 1847 to “One single street, named the Strand, leading to St. Paul’s” to account for the capitalised casual Strada [5]. Despite the spread of the mistake, there seems to be little doubt today that Trevisan meant Cheapside, cf. [6].

The York Water Gate today. This style of architecture, that Andrea Trevisan so liked, would come into style later than the Italian ambassador would live to see. Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net).

– Writing the Strand today –

Now you have seen what previous visitors have had to say, what about the Strand would make it onto your own postcard, diary, or letter home? Are there eateries that stay in your memory, favourite shortcuts, or annoyances that have you avoiding the main road? Leave your comments below, or be in touch with us if you’d like to share lengthier memories!

Sources

[1] Giordano Bruno (Stanley L. Jaki ed.), The Ash-Supper Wednesday, The Hague: Mouton, 1975

[2] Stendhal, Oeuvres Intimes, Volume I, Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, Paris: Gallimard, 1955

[3] Kent’s Original London directory, London : H.-K. Causton, 1818

[4] Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, Calendar of State Papers Relating To English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, London, 1864, Volume 1, pp. 1202-1509 (accessible at https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/venice/vol1/pp267-276)

[5] Camden Society, A Relation, Or Rather a True Account, of the Island of England: With Sundry Particulars of the Customs of These People, and of the Royal Revenues Under King Henry the Seventh, about the Year 1500, 1847

[6] Anne F. Sutton, Marcellus Maures alias Selis, of Utrecht and London, a Goldsmith of the Yorkist Kings, 2007