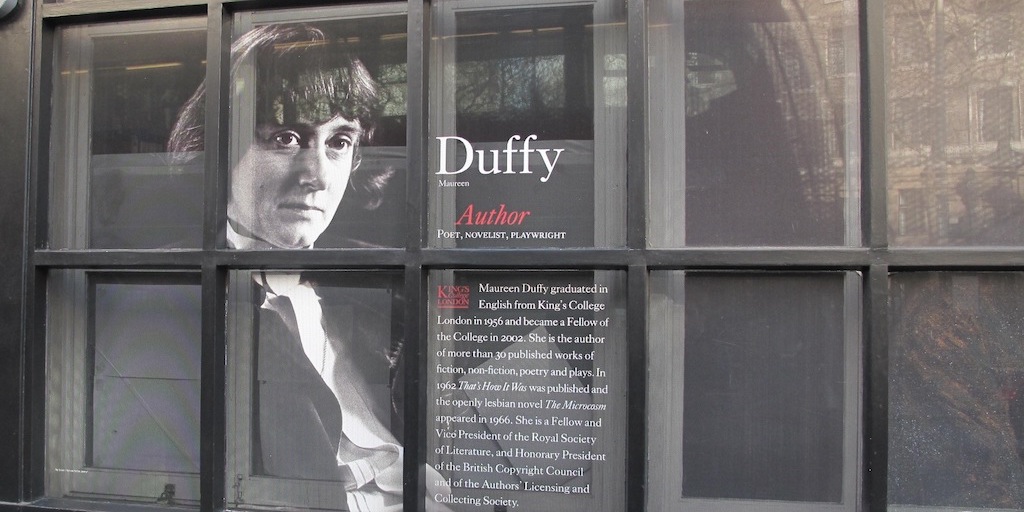

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

by Christine Kenyon Jones

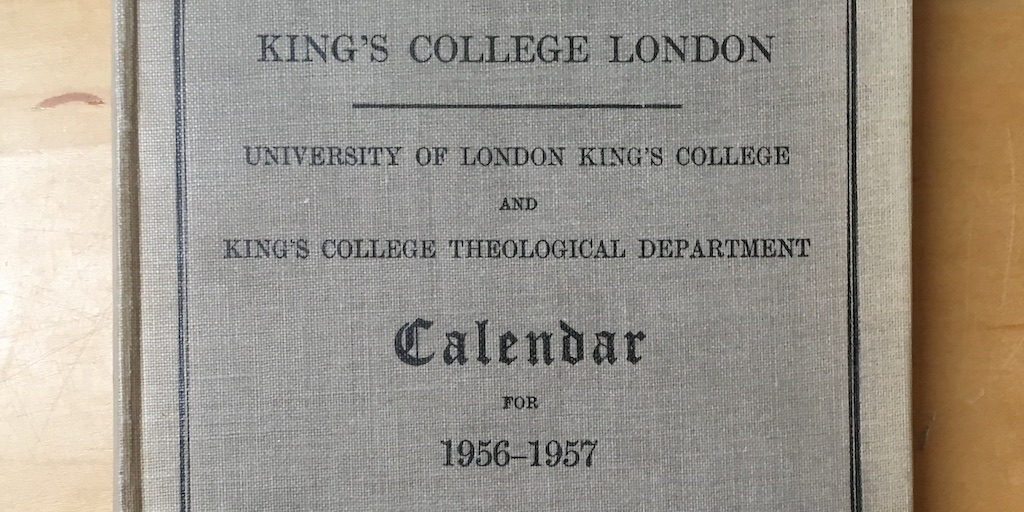

I’ve been asked to speak briefly, with my hat on as the College’s informal historian, about what King’s was like in the time that Maureen Duffy was here, between 1953 and 1956. I’ll be sharing with you what I’ve dug out from sources including the College histories and archival material.

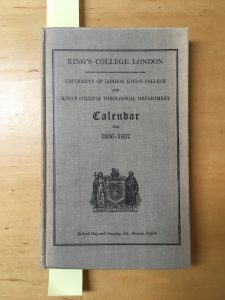

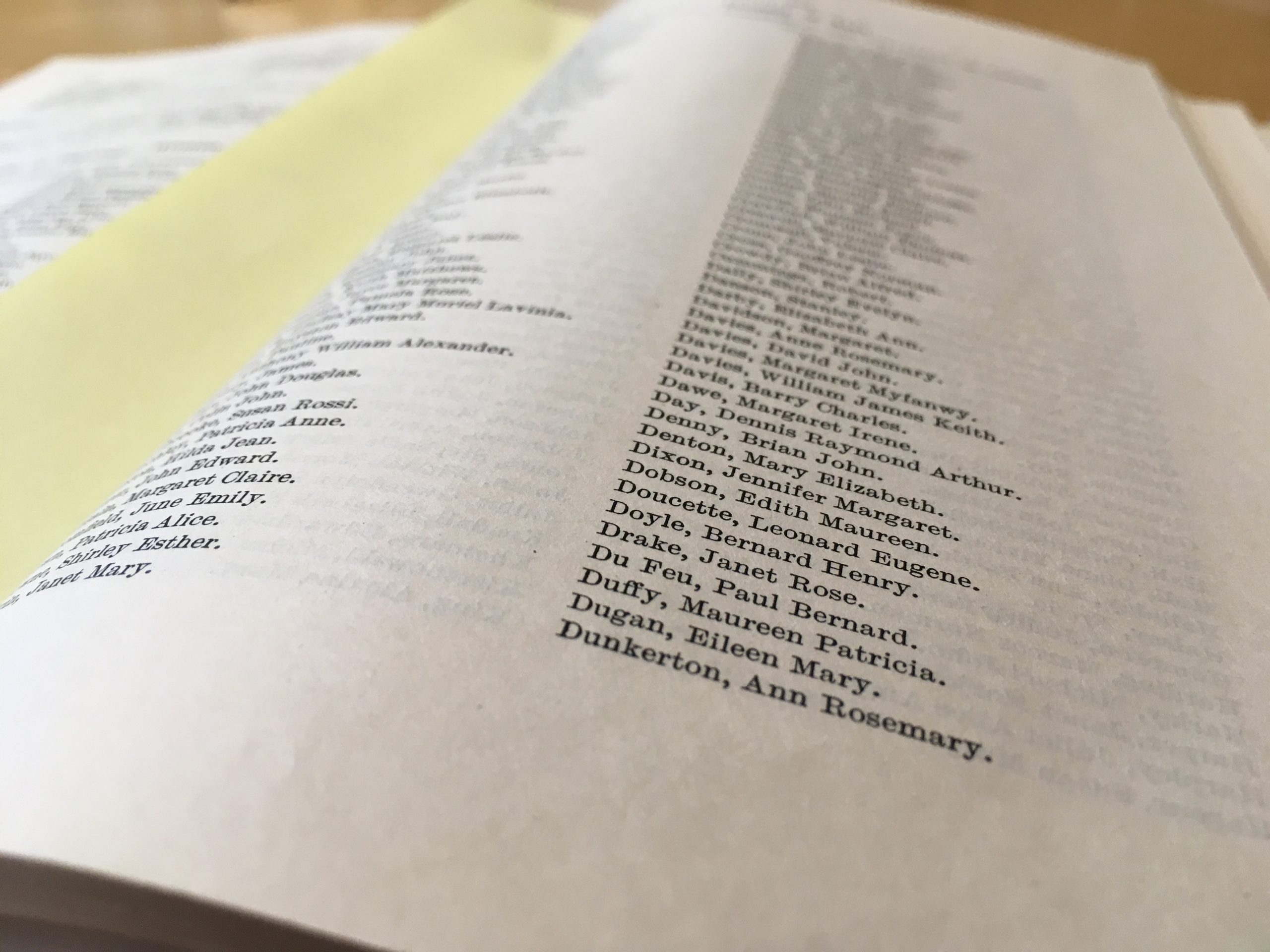

Today, King’s has over 25,000 students, on five different campuses. By contrast, the 1953-4 King’s College Calendar tells us that in those years there were just 2,226 students, all of whom were based here, at the Strand.

Just over 1,700 of these were full-time undergraduate day students; some 100 were part-time students; 315 were taking a course for a higher degree or diploma; 82 were studying for a postgraduate certificate in education (to become teachers), and 26 were undertaking independent research.

To judge from Brenda Maddox’s biography of Rosalind Franklin, who worked at King’s between 1951 and 1953, King’s was then a pretty depressing place. Maddox explains:

'In 1951 the contrast between Paris, which had escaped the attentions of the Luftwaffe, and London, which had not, was all too apparent.

The main quadrangle at King’s [...] was occupied by a bomb crater 58 feet long and 27 feet deep. The Biophysics Unit in the basement wound round the pit, which was being excavated to build the new physics department. The South Bank seen from across the Thames was simply piles of rubble. London was depressing, at its bleakest since the outbreak of war, with bomb sites used as car parks, cracked buildings propped up by wooden buttresses and makeshift housing everywhere. [...] Food was still rationed, and sallow faces showed the effects of years of privation'.[1]

Maddox describes London in this period as ‘a man’s city, a place of furled umbrellas, bowler hats, men’s clubs and gentlemen’s tailors’, and points out that ‘to the expatriate writer Jean Rhys it was “patriarchy personified”’.[2]

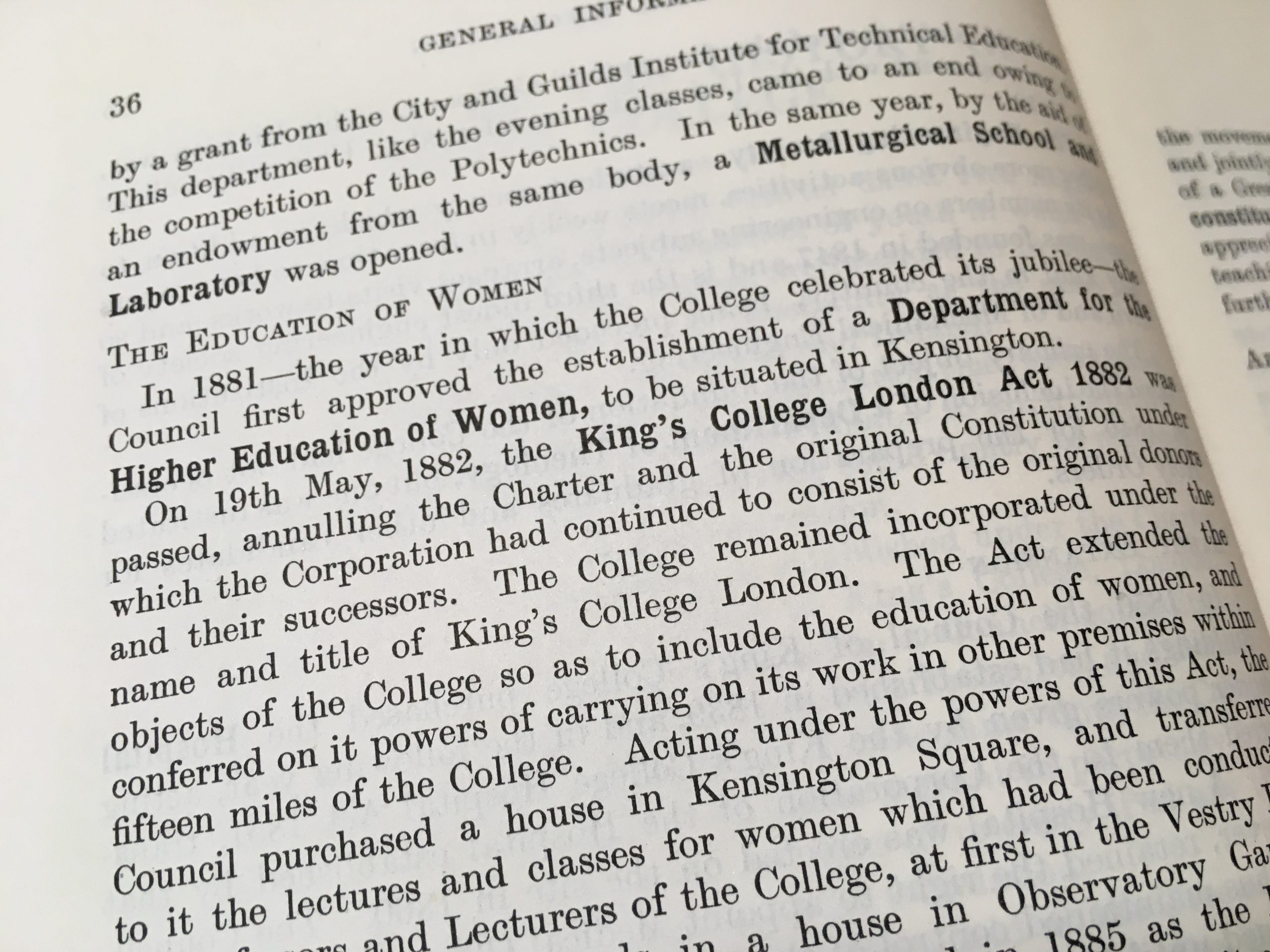

Women were not allowed in the King’s senior common room, but this was common in universities at the time. In fact, at University College London, which had the same arrangement, when the women academics were polled they actually chose to retain the status quo.[3]

Dr Peter Noble, who had become Principal of King’s in August 1952, and is described as a ‘friendly and caring person who could sometimes be found sitting, talking and drinking a cup of tea with the maintenance staff’, soon changed the arrangement, introducing a shared dining room for male and female members of staff.[4] And it was during Maureen’s time here that the ‘Senior Woman Student’ for the first time was able to become (ex officio) an officer of the Student Union Society.[5]

Maddox does also point out that:

'by mid-summer of 1951 the atmosphere in Britain had brightened considerably. The Festival of Britain opened, designed to lift the country out of the doldrums. [… This was] A £12 million, five-month expression of nationalistic faith in the British imagination to conquer new worlds - in art, in architecture and, not least, in science'.[6]

And, she says, ‘In June 1952 the hole in King’s courtyard was filled at last. The new physics and engineering laboratories were opened’.[7] So that will have happened just before Maureen arrived here. Nevertheless, the members of an official visiting party from the University Grants Committee in 1955 were ‘shocked' by the physical conditions in which so much of the work of the College had to be carried on.[8]

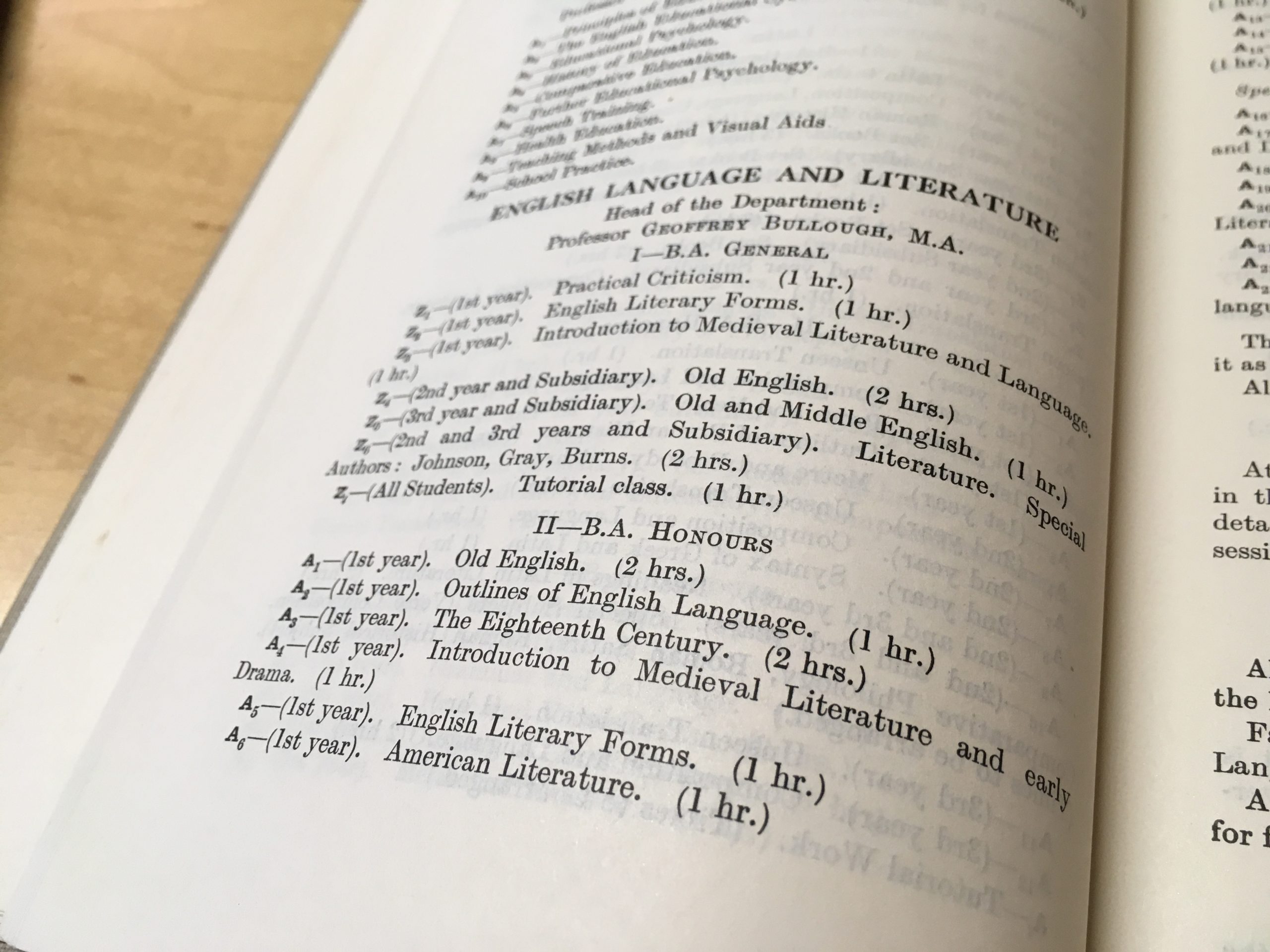

According to the College’s Calendar, describing the year 1953-4, the Department of English Language and Literature then had 30 first-year students, 30 second years and 28 third years, with 33 postgraduates. It was headed by Geoffrey Bullough, Professor of English Language and Literature at King’s from 1946 to 1968. Bullough was soon to begin publishing the hugely influential eight volumes of his Narrative and Dramatic Sources of Shakespeare (between 1957 and 1975) and Shakespeare the Elizabethan (in 1963).

The Department’s Reader in English Language and Literature, Geoffrey Garmonsway (author of, for example, Beowulf and its Analogues and Mediaeval Literature and Civilisation: Studies in Memory) was away as an exchange teacher at the University of California in 1953-4.[9] He was replaced by Professor William Matthews of UCLA, an authority on the London dialect and on British and American diaries, who delivered a lecture on Chaucer’s self-portrait.

The English Department’s permanent lecturers were W A Armstrong; J A Sheard (who lectured in philology), and Dr Frances M Mack, who had been editor of Seinte Marharete the Meiden Ant Martyr for the Early English Text Society in 1934.

Also lecturing in English was the man described by one alumna of the time as the ‘glorious eccentric’, John Crow, who came to King’s in 1946 having taken a pre-medical degree at Oxford followed by boxing journalism, crime reporting in New York and wartime school-mastering.[10] Crow was Churchwarden at St Clement Dane’s; editor of the New Arden Romeo and Juliet, and author of Folklore of Elizabethan Drama (published in 1947).[11]

The assistant lecturers were P M Yarker (editor of the works of Wordsworth, Thomas Love Peacock and others, whose editions I see are still in print), together with M A M Roberts; E Mary; M Taylor and Cecily Clark.

Cecily Clark edited The Peterborough Chronicle 1070-1154 for Oxford English Monographs in 1958 and went on to become Director of Studies in Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic at Gonville and Caius College Cambridge between 1966 and 1985. In 1954 she wrote an interesting and sympathetic letter to the Spectator to protest against Sir Compton Mackenzie’s statement that the task of the university teacher is:

'growing more arduous all the time on account of the ever-increasing number of State-aided students, many of whom nowadays have to be guided like schoolchildren'.[12]

‘[T]o suggest as Sir Compton seems to,’ Clark wrote,

'that the intellectual quality of a student is determined by the source of his fee-payments seems to me unfair. Of course a student may be helped or hindered by his home background, but it is surely not the rich home which gives advantages, so much as the one which is both educated and sympathetic, whatever its financial standing'.[13]

There was evidently quite a debate about these new, state-supported students, and Dr W R Matthews, Dean of St Paul’s, a former Dean of the College, commented in the King’s Review in 1949 that when students had been forced to live on their own, often meagre, resources, it had caused many hardships; but at least they had had an attitude of independence which they were now tending to lose. Present students, he said, were tending to feel, more and more, that it was their right to be completely provided for, and they often carried this over into the world at large.[14]

As we can see from the expertise of the English Department’s staff that I’ve outlined, there was a concentration of specialists in Old English and mediaeval studies, and this is reflected in the classes Maureen would have taken.

In her first year, it looks as if Maureen’s week would have comprised:

- two hours of Old English

- one hour on ‘Outlines of English language’

- one hour on the ‘Introduction to Mediaeval literature and early drama’

- one hour on ‘Practical Criticism’

- and only two hours on the literature of another period – in this case, the eighteenth century.

The proportions were similar in the second and third years.[15]

There was, however, more choice in classes in ‘Special subjects’ for second- and third-year students, which included ‘History of literary criticism’; ‘English literature since 1880, poetry’; American literature; Old Norse; ‘The Classical background to English literature’, Anglo-Saxon archaeology; ‘Palaeography and bibliography’, and ‘Old English, Gothic and other Germanic languages’.

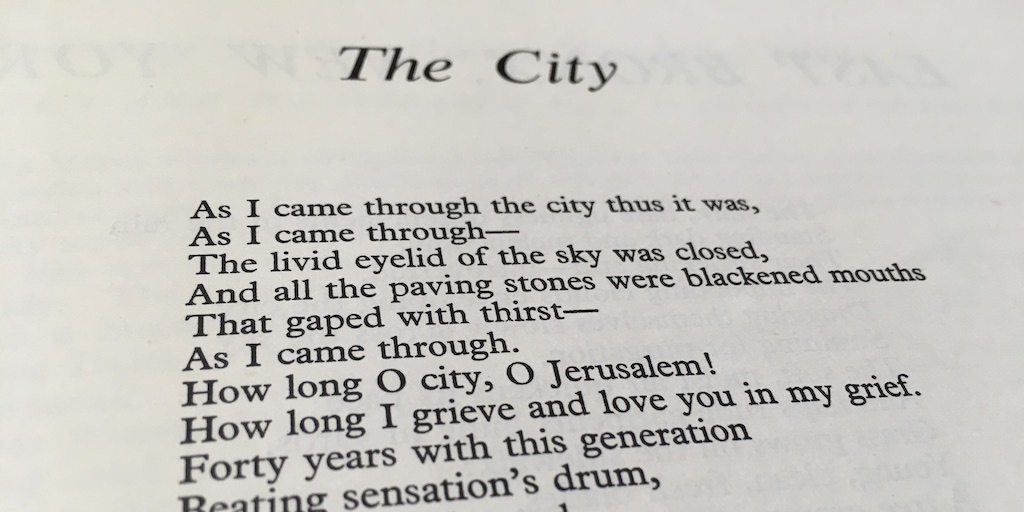

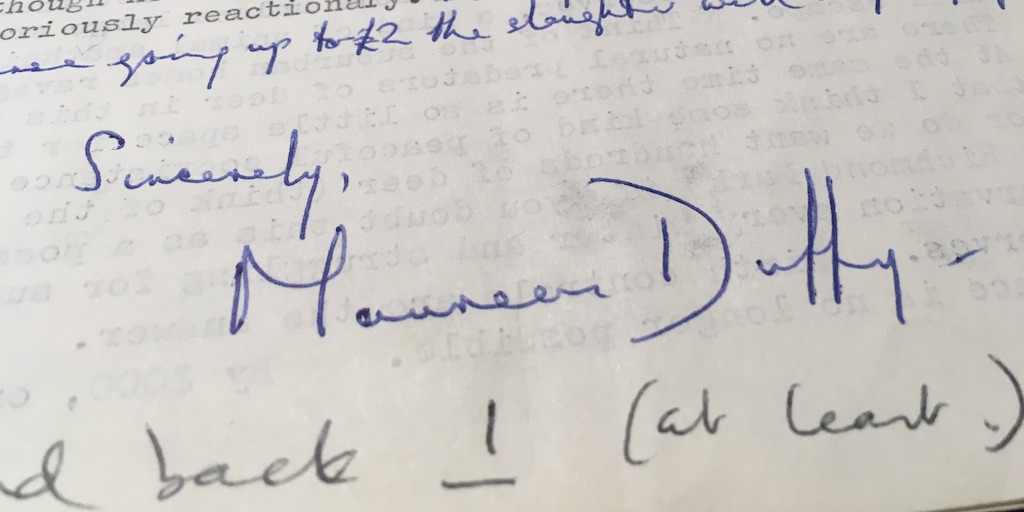

Maureen commented in a 2013 interview in the College’s alumni magazine, In Touch

'The great thing that I kicked against at the time was the compulsory Anglo Saxon, Old English and compulsory Middle English. And yet it’s the thing I return to again and again and it has been absolutely seminal to my writing'.

Furthermore, she modestly described herself as:

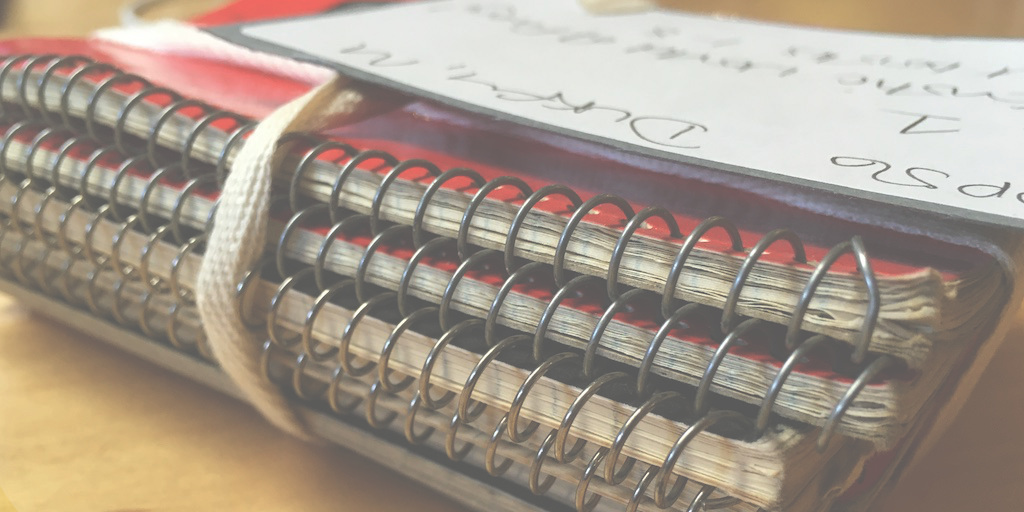

'not a good student, because I spent a lot of time writing. In my third year, when I should’ve been doing my assignments, I wrote my first full-length play, which eventually won the City of London Young Playwrights Award'.[16]

There were several College and London University halls that provided rooms for women students, including King’s College Hall at Denmark Hill and Canterbury Hall and College Hall in Bloomsbury. Rates per term for partial board ranged from about £95, for a shared room, to around £120 for a single room, which translates to £2,837 now for a (presumably) 12-week term, or about £240 a week: considered to be very expensive.

There was also a University Lodgings Bureau, which could provide ‘addresses in most London districts, visited and carefully classified.’ However, the College Calendar warned, ‘Owning to the present shortage of rooms in London it is not possible to guarantee that the exact type of accommodation desired can be provided’.[17] Maureen lived in lodgings in Ladywell, Lewisham, SE13, with a Mrs Lamb and her sister, and she had a bedroom and a tiny kitchen and use of the bathroom.

One of the features of the fictional Queen’s College that Maureen describes in her 1975 novel Capital is the ‘walls lined with the original grimy students’ lockers in institutional dark oak’. There were, she says, ‘far too few for the increased numbers [of students].’ The College Calendar for these years also describes the lockers, which are, it says, ‘placed in the corridors, in the lobby leading to the Anatomical Department, and in some of the classrooms.’ And, it warns severely, ‘No other lockers or drawers may be used other than those provided by the College. [...] Each student will be required to pay for any wilful damage to his locker’, with a new lock costing ‘3s 6d’. There is in fact nearly a page of instruction about the lockers in the Calendar for 1953-4![18]

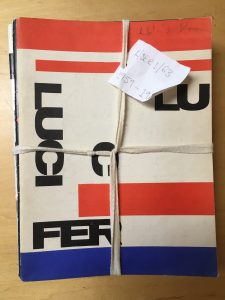

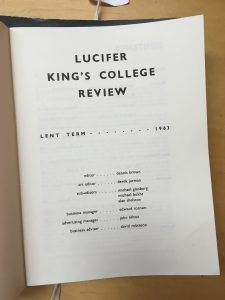

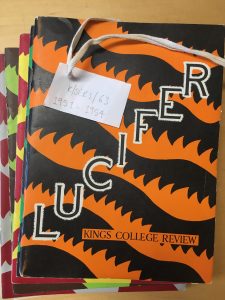

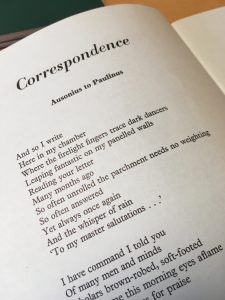

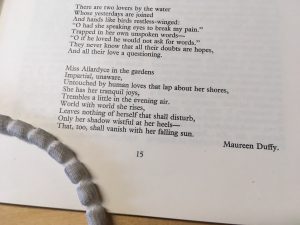

The Calendar also mentions ‘Lucifer - King's College Review, the literary magazine, [which] is published once a term’.[19] This magazine, on which Maureen worked as a sub-editor in 1955 and 1956, was first published in 1899, and it attracted contributions from, for example, B S Johnson, Helen Cresswell and Derek Jarman.

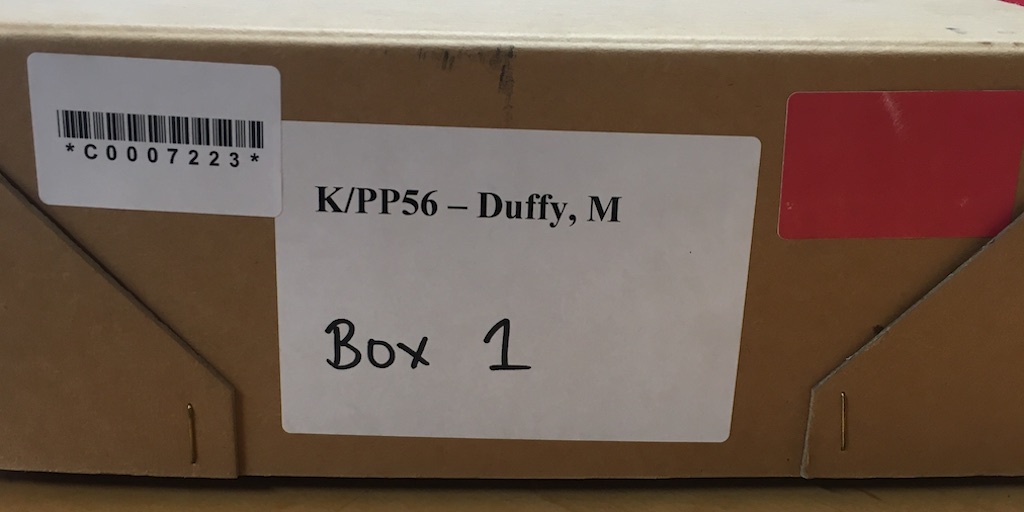

Editor’s Note: Patricia Methven discusses a variety of fascinating material relating to Maureen’s work in the College Archives, and there was a display of some of this material in the cases in the entrance hall of King’s in 2013.

I’ll just finish with a quick round-up, in no particular order, of other snippets of information I have found relating to Maureen’s years here.

In 1953 the College’s celebratory Commemoration Week was held towards the end of the Michaelmas or autumn term. This featured a debate, a concert, a supper and dance in College, as well as a ball at Claridge’s and a new introduction that year was a film premiere, which was apparently ‘much enjoyed’. The Drama Society that year performed George Bernard Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra.

One noteworthy event in February 1955 was the Classical Society’s performance in the Great Hall of Euripides’ Medea, following their performance of Hippolytus in November 1953.[20] The play received a very favourable review from The Times, which singled out in particular Pat Moss as Medea, with ‘a rich voice, dignified presence and some command of pathos’.[21] A year later Sophocles’ Electra was performed, and this success led to the establishment of the Greek play as an annual fixture at King’s, still continuing today.

On the last day of the Michaelmas term 1955 there was a visit by the Duke of Edinburgh, who was a Life Governor of the College, and also in 1955 the Chesham bridge linking the main building of the College with 23 and 24 Surrey Street, was opened.

However, in 1956 ‘The Somerset’ pub, beside the main gate in the Strand, which was known to everyone as ‘Finch’s’ and had provided generations of King’s students with liquid refreshment and become part of the College’s history and tradition, closed its doors for the last time, to be taken over by the German Department.[22]

References

[1] Brenda Maddox, Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA (London: Harper Collins, 2002), p. 125.

[2] Maddox, p. 126.

[3] Maddox, pp. 127-8.

[4] See Gordon Huelin, King’s College London, 1828-1978 (London: University of London, 1978), pp. 115-6.

[5] King’s College London Calendar, 1954-5, held at the King's College London Archives.

[6] Maddox, p. 149.

[7] Maddox, p. 181.

[8] Huelin, pp. 120-121.

[9] Garmonsway was also the editor of An Early Norse Reader (1928), and The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1953).

[10] Letter from Moilly Mahood, English, 1941, In Touch: King’s Alumni Magazine (Autumn 2013), p. 44.

[11] Letter from Geoffrey Weekes, English, 1952, In Touch: King’s Alumni Magazine (Spring 2013), p. 44.

[12] Letter written by Cecily Clark in protest against Sir Compton Mackenzie's statement on university teachers, Spectator, 1954.

[13] Letter written by Cecily Clark in protest against Sir Compton Mackenzie's statement on university teachers, Spectator, 1954.

[14] On the College’s response to the introduction of state-supported students, see Huelin, p. 107; on the effect of the introduction of student grants in 1945, see Carol Dyhouse, ‘Going to university: funding, costs, benefits’, <http://www.historyandpolicy.org/papers/policy-paper-61.html#funding> [accessed 26 November 2013].

[15] 1953-4: 2nd year classes: History of the English Language (1 hour); Old English (2 hours); Middle English

prescribed texts (2 hours); Middle English prescribed texts Chaucer and Langland (1 hour); Shakespeare (1 hour) and English literature 1798-1860 (2 hours). 3rd year classes: Middle English Chaucer and Langland (1 hour); Shakespeare (1 hour); English Literature 1798-1860 (2 hours); Shakespeare texts and bibliography (1 hour) and Philology and History of the English language (1 hour).

[16] In Touch: King’s Alumni Magazine (Autumn 2013), p. 6.

[17] King’s College London Calendar, 1953-4, p. 48.

[18] King’s College London Calendar, 1953-4, p. 48.

[19] King’s College London Calendar, 1953-4, p. 57.

[20] See history of the Greek Play, https://www.kcl.ac.uk/classics/about/greekplay/history-greek-play/1950s/index.

[21] Huelin, p. 119.

[22] Huelin, p. 121.

Sections and Chapters

Duffy and King's introduction

Katie Webb

Finding Maureen Duffy in the Archives

Patricia Methven

King's in Maureen Duffy's time

Christine Kenyon Jones

Kings, and Queens, Histories in Fact and Fiction

Clare A. Lees

Panel Summary: the city as a space for new possibilities

Phoebe Blatton

Writing, Rites, and Rights

John Stokes

A Window for Maureen Duffy

Clare Brant

Fighting and Writing introduction

Katie Webb

Duffy and the European Writers' Congress

Lore Schultz-Wild

An 80th Birthday Honorific Speech

Ingrid Protze

Memories of the German Writers' Union

Sabine Herholz

On Maureen

Katalin Budai

A copyright warrior and a true defender of rights

Olav Stokkmo

Recognising writers: responses, records, royalties

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy's contribution to gay rights and lesbian visibility

Jill Gardiner

For Maureen Duffy, Poiêtes

Karen Gevirtz

Editor's introduction

Katie Webb

Maureen Duffy: Scrivener and Prophet

Charles Lock

Words that count: Maureen Duffy

Marina Warner

Browse articles on Duffy and King's