‘that Strand which is lost as Atlantis’: Arthur Machen’s memories of the Strand

Posted in 1800-1899, 1920-1929, 19th Century, Places, Retail, shops, Strands, streets and roads and tagged with Arthur Machen, books, Dickens, G.M.W. Reynolds

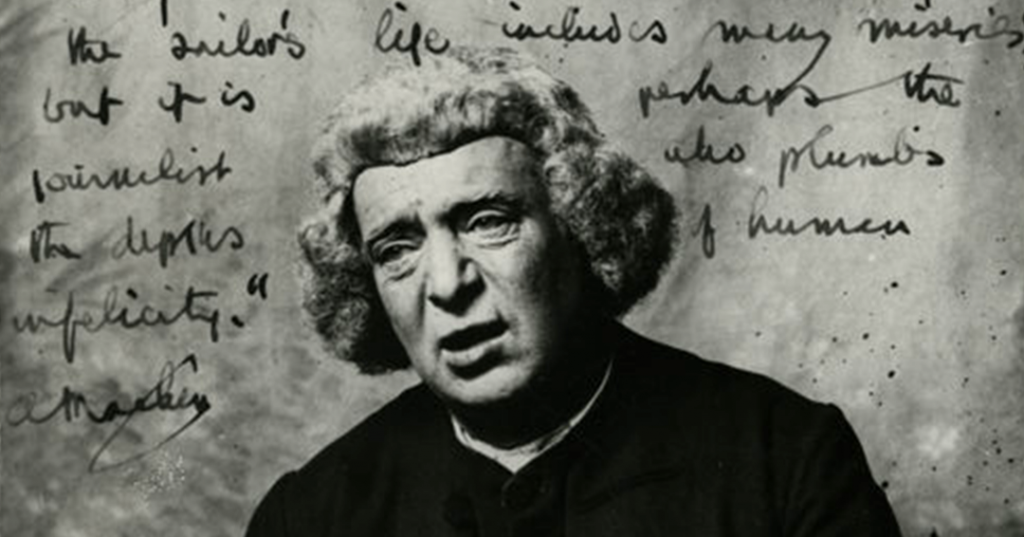

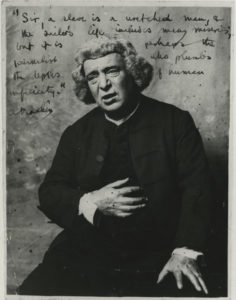

Portrait of Machen in period costume (image via the Harry Ransom centre)

Mystic, theatre critic, teller of weird tales and tramper of London’s obscurer byways and thoroughfares, Arthur Machen was also very fond of the Strand. Available through the Internet Archive (courtesy of the University of California libraries) his memoir of the 1870 and 1880s, Far Off Things (Martin & Secker, 1922) recounts ‘the first time I saw the Strand, and it instantly went to my head and to my heart, and I have never loved another street in quite the same way. My Strand is gone for ever; some of it is a wild rock-garden of purple flowers, some of it is imposing new buildings; but one way or another, the spirit is wholly departed. But on that June night in 1880 I walked up Surrey Street and stood on the Strand pavement and looked before me and to right and to left and gasped. No man has ever seen London ; but at that moment I was very near to the vision – the theoria – of London.’

While Machen describes the Strand of his youth as being ‘as lost as Atlantis’, he also suggests how walking the `strand can cast us still further back in time

‘Nothing could be more urban or urbane than the Strand and yet it had grown, as the green brake grows, as the cathedrals and the country houses of England grew from age to age, gathering beauty as they increased. The Strand was an altogether English street, and it was the very heart of London. In it, or beside it, were the theatres and the bookshops and the cookshops; to north and south odd passages and stairs and archways admitted the curious into the oddest places and quarters. You were weary of the traffic and the pattering feet? Then you could turn into New Inn or Clement’s Inn and enjoy deep silence. You wanted to see the old hugger-mugger of the London back streets, dark taverns of the eighteenth century, where men had lain hidden from the hangman? Here was Clare Market for you. You had heard that ‘Elzevirs’ were very rare and curious books, and would like to see an Elzevir? You would lose your opinion of their rarity, for you would see as many Elzevirs as any man could desire in Holywell Street, where I believe they were to be bought by the sack, as if they had been coals. And Elzevirs apart; the naughty prints and books of Holywell Street were as good as a play. For I believe that the Row had turned naughty somewhere in the early ‘fifties; it had then got in its stocks – and had kept them. Here were the works of G.M.W. Reynolds in large volumes; Mysteries of the Court of St. James, and such weariness. Here was the faded coloured engraving of a young female of extreme gaiety – with ringlets, and the appearance of the chambermaid in the once-famous print, ‘Sherry, sir’. And with all the curiosity, and variety, and oddity and richness of the Strand, it had the while a manner of snug homeliness and cosiness and comfort about it which was quite inimitable. To be in the Strand was like drinking punch and reading Dickens. One felt it was such a warmhearted, hospitable street, if one only had a little money. Unfortunately, I was never on dining terms, as it were, with the Strand; but I always felt that if it only knew me it would have called me ‘old boy’ and given me its choicest saddles of mutton and its oldest port, and I felt grateful.’