Billy Waters: The Busker of the West End

Posted in 18th Century, 19th Century, Musical, Places, Theatrical, entertainment, people, theatres and tagged with Adelphi Theatre, Black presence, History, London history, homelessness, performance, theatre

Thus poor Black Billy’s made his Will,

His Property was small good lack,

For till the day death did him kill

His house he carried on his back.

The Adelphi now may say alas!

And to his memory raise a stone:

Their gold will be exchanged for brass,

Since poor Black Billy’s dead and gone.

(section from will of Billy Waters, from Museum of London Docklands)

William (Billy) Waters (c.1778–1823) lived the life of a character, at times perhaps involuntarily. This much is apparent from his own will, written in verse, in third person. His inclination to describe himself as nearly a fictive being, encapsulating his life within eight lines that put at the forefront his ragged humanity and fatal poverty, provides for a stark contrast between famous figures and the actuality of their living conditions.

As a former American slave, who is thought to have exchanged his servitude to become a part of the British navy, Waters had a remarkably difficult life which was often glossed over in favour of praising his good cheer. Having lost one of his legs on the ship ‘Ganymede’ where he fell from the rigging, he settled in London. His trifling naval pension forced him to find other means of earning to make ends meet and support his wife and two children. The ‘house he carried on his back’ reflects the meagre allowance and lack of possessions he and his family endured, in a constant state of near-destitution while residing in the parish of St Giles, at the house of one Mrs Fitzgerald on Church Street.

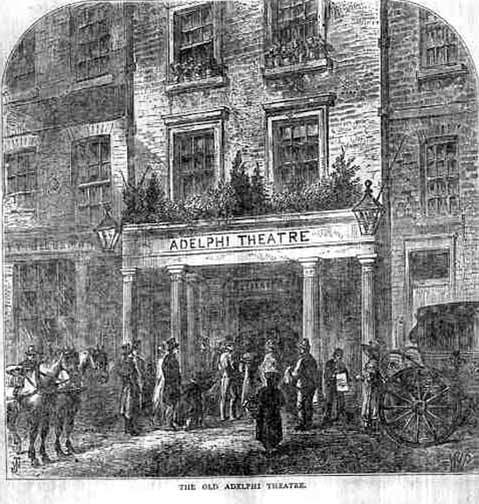

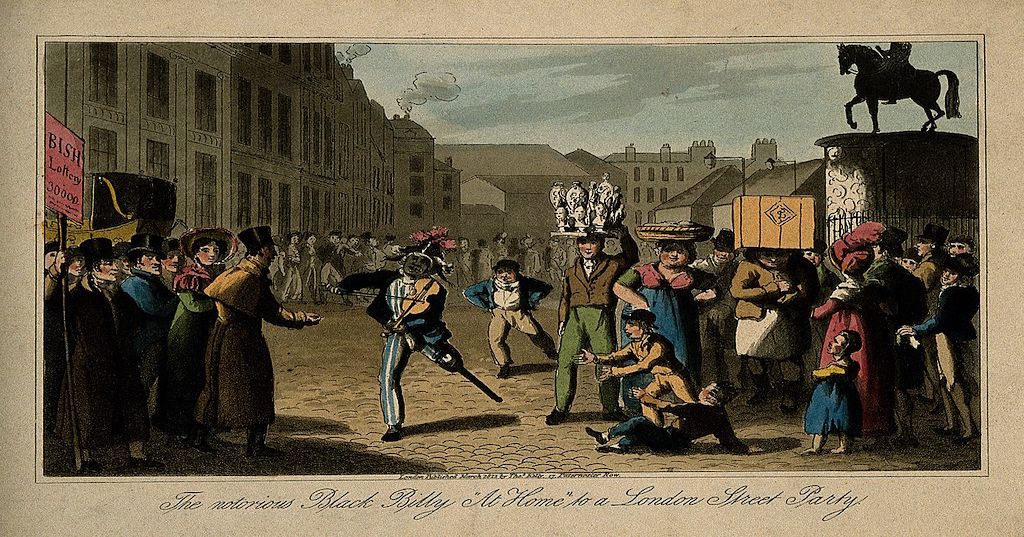

With a wooden leg, a sailor’s jacket and a hat adorned with feathers, he became a regular spectacle in the area, dancing and fiddling his way into the popular consciousness of London. He channelled his talent and passion for theatrics while busking outside the Adelphi theatre, entertaining the visitors before and after plays. He was fondly recalled by the dramatist and writer Douglas Jerrold, saying, ‘Who ever danced as he danced? Waters was a genius’. The presence Waters had always stood at odds with his immense financial misfortune. While his genius was rewarded by browns (half-pence coins) from the purses of the passers-by, he refused to go as far as to flaunt his theatricality on the real stage. In 1821, despite having been offered to appear as himself in the Moncrieff adaptation of Pierce Egan’s popular book Life in London, or Days and Nights of Jerry Hawthorne and his elegant friend Corinthian Tom, he refused. His character was instead played by Mr Paolo, in an attempt to depict the quintessential London street life. The play ran for over 300 nights and was also performed outside London at Caledonian Theatre, Edinburgh.

The unexpected rejection of a solid theatre gig potentially mirrors Waters’s reluctance to become a fully-fledged actor persona, anchoring him instead in the London streetscape where he could entertain as he chose and liked. Hence an offer ‘to appear as himself’ in a theatre play was exchanged for remaining fully himself, as a public busker among the wandering crowds.

Even though the stage production where Waters was immortalised reaped the fruits of success, the real person behind the character continued to experience hardship. Running into further financial troubles, he was forced to carry his fiddle to the pawnbroker’s.

Given his long-lasting relationship to the musical instrument, the moment of parting with it defined the scarcity of his circumstances, rendering it impossible to continue his career as an entertainer in a last attempt to feed his family. The peg leg, which had previously saved him from arduous debtor punishments, would have met the same fate had it not been too worn out to sell. In the end, Waters resorted to entering St Giles’s workhouse. Due to illness, he was no longer capable of undertaking any sort of employment, nor did he participate in regular workhouse duties — often entailing long hours of work as ‘payment’ for lodgings to the able-bodied. After ten days spent completely bed-bound, Waters lost the battle for his life at the age of 45.

Staffordshire figure of Billy Waters (1820). From John Howard Antique Pottery.

Plaster statuette of Billy Waters by Robert Shout (1821). From The Print Shop Window.

Billy Waters as a notoriously known character continued to appear in art post-mortem, especially in porcelain and ceramic figures and illustrations. Billy appeared in a number of prints by artists such as George Cruikshank, in books such as Cries of London Drawn from Life by Thomas Busby (1823). These recreations often depicted him as carnivalesque, almost Dickensian, registering the busker’s very existence as more of a public property, a phenomenon to profit from, than a real human being. All these paraphernalia are rarely accompanied by an extensive account of its inspiration’s life, prove how Waters’s rise to fame had him appropriated to entertain the more fortunate theatre-goers and art-buyers, and did not bring any fortune to Waters himself.

Further reading:

Billy Waters, a one legged busker, in a crowded London street. Coloured aquatint, 1822. Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark, Wellcome Collection gallery (2018-03-23): https://wellcomecollection.org/works/c4vcv53z

‘Billy Waters, Adelphi Theatre, the Strand’ Museum of London Docklands, https://www.museumoflondon.org.uk/museum-london-docklands/whats-on

Nelson, Alfred L., Cross, Gilbert B., Donohue, Joseph, The Adelphi Theatre Calendar revised, reconstructed and amplified. 2013 and 2016, Originally published by Greenwood Press as The Sans Pareil Theatre 1806-1819, Adelphi Theatre 1819-1850: An Index to Authors, Titles, Performers, 1988, and The Adelphi Theatre 1850-1900: An Index to Authors, Titles, Performers and Management, 1992.

Shannon, Mary L. ‘The Multiple Lives of Billy Waters: Dangerous Theatricality and Networked Illustrations in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture’ in Nineteenth-Century Popular Culture. Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film. 2019;46(2):161-189.

Walford, Edward, Old and New London, 1879-1885, (London: Cassell, Petter, and Galpin)