Kingsway’s Ghost Station: London’s first underground tramway

Posted in 20th Century, Transport, streets and roads and tagged with 20th century, History, Kingsway, central London, construction and demolition, everyday life, london transport, strand, subways, trams, urban design, working class London

For seventy years now, the once-bustling environment on the platforms of Kingsway Tram Tunnel has been displaced by darkness and disuse. Previously a key transit point connecting north and south London, the tunnel now fades into the backdrop of Kingsway’s ceaseless motor and pedestrian traffic.

Opened in 1906, Kingsway’s Tunnel was fully operative for only 46 years before its last tram drifted down the conduit tracks in 1952. In its short life, Kingsway Tram Tunnel became a shining mantle of the early-20th-century working class in London—despite its construction uprooting the very people it eventually served.

A tram on the 31 route stopping to pick up passengers in Kingsway Tramway. From the London Transport Museum.

In order to make way for the tunnel—and the wide street we know as Kingsway to which it is connected—the London County Council began ‘clearing’ Holborn’s ‘slum area’ in 1899, part of a series of ‘slum clearances’ conducted by the Council from 1889 to 1907. The Council’s clearance movement was supported legally by Torren’s Act of 1868 and Cross’s Act of 1875, two statutes aimed at rebalancing inner London’s housing supply, as overcrowding was thought to contribute to the higher mortality rates to which such areas were prone.1 Cross’s Act, more clearly demarcated for the redevelopment of ‘slum areas’ than individual homes, provided the basis for the Clare Market Scheme, the project that eventually produced Kingsway.

A tram exiting Kingsway Tram Tunnel onto the heavily-trafficked street above, also known as Kingsway. From Urban75.

Although Cross’s Act obligated relevant authorities to rehouse those displaced by clearance schemes and compensate landholders for their property at market value, confusion among Parliamentarians concerning how the Act should be interpreted led to a diminished level of accountability for those authorities, like the London County Council. In 1882, whilst debating the Artizans’ Dwellings Act, members of Parliament disputed whether the previous housing act (Cross’s) required the rehousing of all displaced or ‘not less than one half’ of those displaced.2 While neither Torren’s nor Cross’s Act explicitly states that authorities can only rehouse one half of those affected by clearance schemes, the result of such confusion was that thousands of residents found themselves cast out of areas being redeveloped.

The Clare Market Scheme, for instance, displaced 3,172 people on its own. Even where rehousing measures were entirely compliant with the language of the Cross’s Act, the resulting housing developments were often erected years after the clearance and largely unaffordable for those it displaced.

One resulting development, Kingsway Tram Tunnel, was a silver lining for working-class persons amidst the rapid redevelopment of inner London. The tram system more generally catered to the working-class, not only because it was inexpensive to use, but because trams could often take workers right to the front door of their factories. Despite, or perhaps because of, their popularity with the working public, the City of London and West End local authorities never allowed tram systems to be introduced to their jurisdictions.3

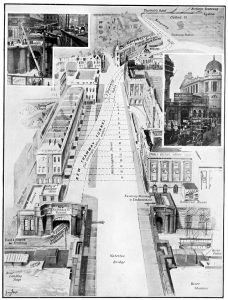

A diagram of the underground passage Kingsway Tram Tunnel provides between Kingsway and the North Embankment. From Sphere Magazine.

Kingsway’s Tunnel was the first piece of transport infrastructure in London designed to move a tram underground. Its initial construction was tall enough to fit a single-decker tram, but in 1929, the tunnel was expanded to fit double-deckers. The double-decker pictured below was traveling along the 33 route, one of four tram lines supported by Kingsway Tramway running between north and south London.

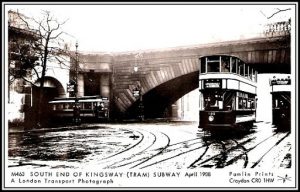

A single-decker tram exiting the Kingsway Tram Tunnel onto the Embankment (left) before the tunnel was expanded in 1939. From London Transport.

A 33 tram exiting onto the Embankment from Kingsway Tunnel’s new double-decker expansion. From Stories of London.

Two 33 trams passing one another at the entrance to Kingsway Tram Tunnel. From Stories of London.

By 1940, most trams in London had been replaced with trolleybuses, and only routes through Kingsway Tram Tunnel and in South London remained navigable by tram. Another decade later, the London Transport Board, which had succeeded the London County Council as the organising force for tram services, began closing routes through Kingsway Tram Tunnel, too.

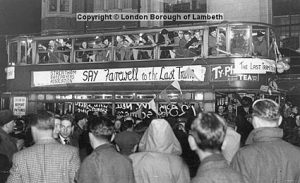

The last tram to grace Kingsway Tram Tunnel with regular service did so in 1952. Not only were the last trams to travel the 31, 33, and 35 routes packed with passengers, but crowds followed along however they could, walking and cycling alongside the tracks. This public outpouring of support speaks to how beloved the tram system was to London’s public—the small piece of that system at Kingsway being no exception.

A crowd of Londoners saying their farewells to the last tram on the 33 route. From Lambeth Archives.

With remarkable continuity since the Tunnel’s closure, magazine and newspaper articles have captured the special role Kingsway Tramway played in London’s history. For example, a 1952 article in Country Life mourned the sense of romance and ‘eternal excitement’ that was lost when Kingsway was put out of use;4 a Guardian write-up argued for the restoration of tram systems in Central London in 1999, naming Kingsway specifically and calling trams a ‘special… kind of moving architecture;’5 and a 2014 Independent piece testifies to the ‘enigmatic pull’ abandoned ‘ghost stations’ like Kingsway have on us.6

Today, that ‘enigmatic pull’ is still alive. Last week, on 12 August 2021, the London Transport Museum began guided tours through the echoey, subterranean passage under Kingsway.7 The Tunnel has been part of the Museum’s virtual guided tour of Holborn since October 2020, and the Museum’s commitment to a new round of tours of Kingsway Tram Tunnel speaks to a strong, unbroken public interest in one of the Strand’s most unique passageways.

Further reading:

- Yelling, J. A., ‘L. C. C. Slum Clearance Policies, 1889-1907’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, (7.3) 1982, pp. 292–303.

- Stilwell, Martin, ‘Housing the Workers in London: Housing Legislation 1850-1914’, Housing Legislation in the 1800s, 2015.

- Wolmar, Christian, ‘In praise of the tram: how a love of cars killed the workers’ transport system’, The Guardian, 6 Jun 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/jun/06/tram-cars-killed-efficient-urban-mass-transport-system-christian-wolmar.

- ‘THE ROMANTIC TRAMWAY’, Country Life (Archive : 1901 – 2005), (111.2882) 11 Apr 1952, pp. 1068.

- Glancey, J., ‘Eye catcher’, The Guardian (1959-2003), 15 Jul 1999.

- Beanland, C., ‘TUNNELS OF LOVE’, The Independent, 25 Sep 2014.

- ‘Kingsway tram tunnel: linking up London’, London Transport Museum, https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/whats-on/hidden-london/kingsway-tram-tunnel-linking-london.