Temple Church: Magna Carta and the Knights Templar

Posted in Medieval, Places, Strandlines and tagged with

The filming location of the Da Vinci Code [2006], survivor of the Fire of London and WW2 bombing, a secret meeting place of a back-stabbing king, the core of the City’s major legal district, and London’s first bank – Temple Church has witnessed milestones in English history.

In medieval London there were ‘more churches than in any other city in Europe and more than a hundred churches within the walls of the old City.’[3] Today, in the Temple area of the City, there are three churches: St Mary Le Strand, St Clement Danes, and the well known Temple Church. The first two date from the late 17th/18th centuries and are located in the middle of the Strand main road).

Temple Church is much older, built by the Knights Templar and consecrated in 1185. It has an especially idiosyncratic history, and its architecture is powerfully quirky. It gives its name to this area of London as well as its local businesses, including bars: Temple Brew House, a ‘temple for beer enthusiasts’; The Knights Templar pub, adorned with knight and crusade-related artworks; hotels, and streets. There are also two of the four inns of court, Middle Temple and Inner Temple, which both have Thames-side leafy gardens with public opening times.

Just off Fleet Street, the Church was relocated from High Holborn and used as the Knights’ headquarters. Part of the Templars’ original purpose was the protection of pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land and the Holy Sepulchre. The Church’s architecture includes the Round Church, which is both the earliest Gothic building in England and ‘one of only four Norman round churches still operating’.

Modelled after the Holy Sepulchre as it functioned in part as a pilgrimage site for those unwilling to undertake the tougher journey to Jerusalem:[4]

In every round church that the Templars built throughout Europe they recreated the sanctity of this most holy place.[5]

Credit: OneLuckyGuy on Flickr

Inside the Round Church are graves – effigies, like a weird indoor cemetery. One of these is of William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, sometimes described as ‘the greatest knight of his age’.[6] If you have read Philip Larkin’s poem, ‘An Arundel Tomb’, you will know of the emotional power of small details in sculpture:

Side by side, their faces blurred,

The earl and countess lie in stone,

Their proper habits vaguely shown

As jointed armour, stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint of the absurd—

The little dogs under their feet.

The effigies in the Church have a more military flavour when compared to the ‘stone fidelity’ of the earl and countess in Larkin’s poem, but seeing the conceit of sleeping stone knights with large shields and unsheathed swords has a powerful effect within a ‘holy place’, harkening back to the original meaning of the Knights Templar, which was ‘chiefly for the protection of the Holy Sepulchre and of Christian pilgrims visiting the Holy Land’.[7]

Magna Carta

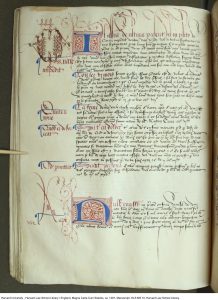

Sequence 97 from the Magna Carta. Credit: Harvard Library

It is worth remembering, too, that religion and law were closely entwined in medieval London, partly due to the power of the Church for which there is no contemporary parallel; the first recorded use of the word ‘church’ occurs in Alfred’s Doom book – dooms meaning laws in this context. This legal and religious link is particularly pertinent to Temple Church. King John used it as headquarters because the Templars were his allies, and from here he issued a charter in 1214 guaranteeing the ‘freedom of the English Church’.[8] This in part paved the way for Magna Carta, where we can read in Article 1:

the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished, and its liberties unimpaired.[9]

‘Great Seal of King John’ showing the King on horseback. Originally attached to Magna Carta, June 1215.

The 1214 charter needs to be seen in context. Pope Innocent III had previously placed England under an interdict for six years and excommunicated the King, which encouraged Philip of France to think of invading. This was a direct result of the king seizing church lands and, later, more property. The charter allowed John to escape war at home and mend relations with Rome.

In 1215 the King also issued the Mayoral Charter from the Temple Church which gave London the right to elect its own mayor, described, along with the 1214 charter, as ‘an important step in the history of Magna Carta’.[10] There is still a presentation ceremony of the City’s choice of mayor, dating back from this time with ‘guilds processing out of the City down the Strand to Westminster in what is still the Lord Mayor’s ‘Show’.[11]

Although the Great Charter was not issued from the Temple itself, William Marshal mediated between the King and the barons in the creation of the document; he also witnessed it, along with Brother Aymeric, master of the knighthood of the Temple, and one of Marshal’s sons, the 2nd Earl of Pembroke. Both of these men are part of the group of four effigies that lie in the Church.

Marshal fought on the side of the King in the First Barons’ War (1215-1217), which John used as an opportunity to ‘replenish his bank balance’, doing exactly the opposite to what he agreed in the Charter.[12] The King fell ill during the war and died on 19th October 1216, which allowed Marshal to then reissue Magna Carta under his own seal the same year.

It is clear that ‘the greatest knight of his age’, then, was a considerable tactician, who played on both sides. King John wanted Marshal to protect his son and heir, Henry III, nine years old at the time of his father’s death, but Marshal was reluctant. He was eventually persuaded by the Papal Legate, and became the third Regent of England between 1216 and 1219.[13] The regency allowed Marshal to ensure the survival of Magna Carta—in complete contrast to the actions of King John and his support of him—by reissuing it under his own seal in 1216 and 1217.

Thereafter the Charter was:

reissued regularly whenever there were problems between the realm and its sovereign and by the end of the 13th century it had become totemic.[14]

The Charter was supposed to curtail the power of the monarch, but it failed in the short-term. The events afterwards demonstrate this all too clearly: John used the Pope to declare Magna Carta null and void, thereby escaping its constraints on his power – a medieval loophole. In many ways the Pope acted as a second monarch, and his decision to annul the Charter sparked The First Barons’ War, throwing England back into disarray – just one instance in the power struggle between Papal, monarchical, and parliamentary rule pre-Reformation.[15]

Magna Carta’s legacy also rests on the emphasis on ‘free man’, his individual rights, and more broadly, ‘the better ordering of our kingdom’.[16][17] Article 39 is an especially good example of this:

No free man shall be arrested or imprisoned or diseased [legally dispossessed of one’s land] or outlawed or exiled or victimised in any other way, neither will we attack him or send anyone to attack him, except by the lawful judgement of his peers or by the law of the land.[18]

Temple Church is described on its website as the ‘Cradle of Common Law’. The first English parliament convened in 1215 with the agreement of the Charter, and throughout the thirteenth century the Church became an important meeting place throughout the institution’s evolution during the reign of Henry III.

Temple Church signage

‘Templar’

Templar statue outside Temple Church. Credit Tristan Tetteroo

Circling back to the original foundation of the Church, it is important to bear in mind that the word ‘templar’ may also refer to:

A barrister or other person who occupies chambers in the Inner or Middle Temple.[19]

We find it used in this precise sense in 1815 in The Letters of Charles and Mary Lamb: “I am a Christian, Englishman, Londoner, Templar”.[20]

One of the Inner Temple lawyers or templars in the seventeenth century was John Selden. During England’s most crucial struggle between monarchy and parliament, leading to the Civil War [1642-1651], he invoked Magna Carta to try to limit the Crown’s power. He was imprisoned by the King in 1621 and is buried in Temple Church. It is in part thanks to his efforts that parliamentary government became more autonomous.

Reading from the official website of the Temple:

Inner Templars were conspicuously vehement in the defence of English liberties. Middle Templars had already sown the seeds of liberty much further afield.[21]

Much further afield includes English colonists – also templars – who shaped colonial law in parts of America. Walter Raleigh was part of these expeditions, where the revised and reissued Magna Carta was drawn on for a ruling basis much later in the eighteenth century, by Signatories for the American Declaration of Independence and the American Constitution.

Reading from the original 1776 Declaration, it is easy to see the similarity between the language of Article 39 in the first drafted Charter and the beginning of the Declaration:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.[22]

‘Feiquan’ & Templar Banking

The other side of the coin, if you’ll forgive the expression, to the Knights Templar was their banking system, sometimes described as the foundation of modern banking. Based on a Chinese system called ‘feiquan’, translated as ’flying money’, invented during the emergence of the Tea trade in the Tang dynasty, the Knights created banks allover Europe:

pilgrims could deposit funds for their venture in exchange for a letter of credit that they could reimburse for the same amount at any of the other, shall we say, branches.

The Templars accrued enormous wealth and power, and were exempt from taxes as a religious order – ironic for an organisation also known as the Poor Fellow Soldiers of Christ:

the Order of the Temple was the world’s major financial institution, a large multinational that concentrated a large amount of very valuable information on kings, princes, aristocrats and wealthy members of the clergy.

These branches included Temple Church and the Temple in Paris, which became the French Treasury, and where there is a Temple Metro station today, which matches Temple on the London Underground.

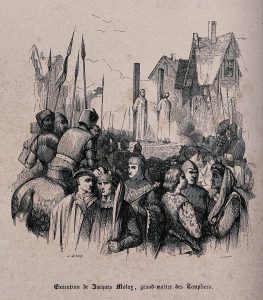

Burning of Jacques De Molay. Credit: Welcome Collection

Ultimately, their wealth was their undoing. King Philip VI of France, who was in major debt to the Templars, conspired with Pope Clement V to dissolve the order; their Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burnt publicly in Paris in 1314.

Knights Hospitaller

After the order was dissolved, Edward II took over Temple Church and it became home of the Knights Hospitaller, a Catholic order whose purpose was to care for sick pilgrims ‘without distinction of race or faith’. Their name originates from the hospital built in Jerusalem in 1080.

The Knights Hospitaller was abolished in 1540 during the Dissolution, and the Temple once again was owned by the Crown. The Order of St John was re-established again during the Victorian age and lives on as ‘a sovereign entity in international law and is engaged in international charity work.’ Its symbol is a white cross on a black background in contrast to the Templars’ red cross on a white background. The white cross is recognisable as ‘an international symbol of first aid’ used by the St John Ambulance. Today, the Temple is maintained by the two Inns of Court, Inner Temple and Middle Temple – an agreement which has lasted since the beginning of the seventeenth century.

There are few buildings in England with a richer history than Temple Church. Linking so many different cultural branches at the heart of the City, as well as familiar names such as De Quincey, Burke, Francis Drake, Walter Raleigh, Christopher Wren, and Edward Coke, it continues to draw historians, film buffs, and worshippers alike.

References

[1] “temple, n.1”. OED Online. December 2020. Oxford University Press. https://oed.com/view/Entry/198928?rskey=4SXRvO&result=1(accessed February 05, 2021).

[2] “church, n.1 and adj.”. OED Online. June 2021. Oxford University Press. https://oed.com/view/Entry/32760?rskey=glotfD&result=1 (accessed July 01, 2021).

[3] London: The Biography, Peter Akroyd. p.92

[4] This information according to: Griffith-Jones, Robin. n.d. Magna Carta 1215–2015 London’s Temple And The Road To The Rule Of Law. London, England: Pitkin Publishing. http://www.templechurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/magna-carta.pdf.

[5] http://www.templechurch.com/history-2/timeline/the-round-church/

[6] Griffith-Jones, R. (n.d.). Magna Carta 2015-2015: London’s Temple and the Road to the Rule of Law. [online] The Temple Church, London. Available at: http://www.templechurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/magna-carta.pdf.

[7] “Templar, n.”. OED Online. June 2021. Oxford University Press. https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/198923?rskey=5MkwQF&result=1 (accessed July 23, 2021).

[8] Griffith-Jones, R. (n.d.). Magna Carta 2015-2015: London’s Temple and the Road to the Rule of Law. [online] The Temple Church, London. Available at: http://www.templechurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/magna-carta.pdf.

[9] The British Library. (2014). English translation of Magna Carta. [online] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/articles/magna-carta-english-translation [Accessed 23 Jul. 2021]. Source: G.R.C. Davis, Magna Carta (London: British Museum, 1963), pp. 23–33.

[10] https://www.london.anglican.org/articles/service-marks-800-years-since-the-introduction-of-the-london-mayoral-charter/

[11]Jenkins, S. (2020). Short History Of London : the creation of a world capital. Penguin Viking.

[12] Lee, C. (1998). This Sceptred Isle : 20th century. London: Penguin.

[13] Aelfthryth and William Longchamp were regents under King Aethelred the Unready and Richard I respectively.

[14] The British Library. (n.d.). The impact of Magna Carta in the 13th century. [online] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/videos/the-impact-of-magna-carta-in-the-13th-century.

[15] Pope Innocent III was a trained lawyer.

[16] The British Library. (2014). English translation of Magna Carta. [online] Available at: https://www.bl.uk/magna-carta/articles/magna-carta-english-translation [Accessed 23 Jul. 2021]. Source: G.R.C. Davis, Magna Carta (London: British Museum, 1963), pp. 23–33.

[17] The Charter was first known as the ‘Charter of Liberties’.

[18] Ibid.,

[19] “Templar, n.”. OED Online. June 2021. Oxford University Press. https://oed.com/view/Entry/198923?rskey=DVs9F2&result=1&isAdvanced=false (accessed July 15, 2021).

[20] Ibid.,

[21] Griffith-Jones, R. (n.d.). Magna Carta 2015-2015: London’s Temple and the Road to the Rule of Law. [online] The Temple Church, London. Available at: http://www.templechurch.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/magna-carta.pdf.

[22] Ibid.,

It’s took me 20 years to find the key to success “I am a Christian, Englishman, Londoner, Templor” to know the history of the great charter of Liberty and the source in which I thank God Almighty for his blessings.

Interesting article. When Philippe Le Bel (Philippe IV and not VI as is said here) ordered the arrest of the Templars all over France, this infamous Friday 13th of October 1307, it is rumoured that a few managed to escape. Indeed, although they were known to hold great wealth in their coffers, nothing much was found in their headquarter in Paris. Legend as it that a convoy of chariots discretely left Paris for the Commanderie of Gisors and then the harbour of Calais, where a dozen or more ships sailed to England. It is well known that the Huguenots would later spread anti-French sentiments in the countries in which they would take refuge, like England, and it is intriguing to think that the Templars could have initiated such a trend in their time. But even more tantalising is the idea that these bankers could have played a part in the making of the City in London. Would you know if the red cross in the City’s logo has any thing to do with the Templars’ red cross emblem?