George E. Street’s Royal Courts of Justice: architectural visions of the Strand

Posted in 1800-1899, 19th Century, Architecture, churches, Medieval, Strandlines and tagged with gothic revival, high victorian gothic, law, London architecture, neo gothic, Royal Courts of Justice, strand architecture

In 1873, George E. Street began building his most visible architectural project: the Royal Courts of Justice. The project, which required eleven years of construction, became one of his last, as Street did not live to see the Courts completed in 1882. According to Street’s son, the New Law Courts project, as it was called then, may even have ‘cost him his life.’1

In February 1866, the judges of the New Law Courts competition invited twelve of England’s ‘most eminent architects’ to design a law building for a site between Carey Street and the Strand, with the purpose of bringing together sixty departments of legal procedure, including the Superior Courts of Law and Equity, the High Court of Admiralty, and an ecclesiastical court. In May 1868, two Courts of Justice Commission decisions, a legal appeal, the influence of another architectural competition, and over two years of debate eventually culminated in the sole appointment of George E. Street as architect of the New Law Courts, now known as the Royal Courts of Justice.

The New Courts architectural competition seemed ordinary enough at its start. Only a few months after inviting architects to submit designs for the New Courts, the Courts of Justice Commission announced a decision. However, this first ruling was not really a decision at all: on 30 July, 1866, the judges announced that no one design could be selected as the best in all respects and split their award amongst two competitors, Street and Charles Barry, causing an uproar amongst competitors and critics alike. It was not until almost another year later—a year of protest and appeal from competitors—that Street was awarded the sole rights to build the New Courts.

What occurred in the year between the judges’ (in)decision and Street’s censure of the bid to create so much tension between Street and the other competitors?

What might the Royal Courts of Justice, and the Strand more generally, look like if Street had not been afforded the rights to build?

What does the Commission’s decision to give sole rights to Street and his design say about their values or vision for London?

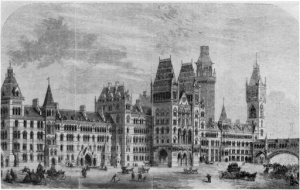

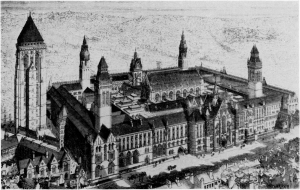

For the entirety of the competition, no one competitor won the support of architectural critics. Edward M. Barry’s design was dubbed an excellent plan by the Builder but labeled monotonous by the Building News. The Spectator applauded William Burges’ design’s beauty but criticized its impracticality. The same outlet praised Alfred Waterhouse’s design as ‘demonstrably the best exhibited,’ but the Athaeneum said Waterhouse’s lacked the ‘Gothic expressiveness’ it should have provided.

Edward M. Barry’s design, Courts of Justice, 1867. From Port: “The New Law Courts Competition”

Alfred Waterhouse’s design, Courts of Justice, 1867. From Port: “The New Law Courts Competition”

William Burges’ design, Courts of Justice, 1867. From Port: “The New Law Courts Competition”

Nonetheless, Waterhouse had been ‘rumoured to enjoy special favour’ and may have been expected to win the New Courts bid. Waterhouse won a plurality—but not a majority—of votes to decide the fate of the competition, garnering the favor of three of seven judges. Ultimately, though, the remaining four judges who favoured either Barry and Street banded together to outvote those who favored Waterhouse. This is likely why the Commission’s decision to jointly award Street and Barry with the rights to build the New Courts was so heavily contested.

Amidst written protest from Waterhouse and a fellow competitor, Raphael Brandon, the Treasury Board referred the judges’ decision to the Attorney-General, citing concern a joint award did not accord with the original terms of the competition. On 14 May, 1868, already over two years since the competition’s inception, Sir John Karslake, the Attorney-General, ruled the award had not, in fact, been a valid one, meaning the Courts of Justice Commission judges needed to coalesce their support around a sole architect in order for the project to move forward under its current terms.

In a way, the judges never made their decision—at least not directly concerning the future Royal Courts of Justice. In deciding between Barry and Street for the Courts architecture, the judges turned their focus to a different competition: one for a new National Gallery. Barry was up for award for the Gallery, as well, so the award for the Royal Courts came down to how the Government could best distribute its architectural talent around the city. Barry was chosen to build the new National Gallery; Street, the New Law Courts.

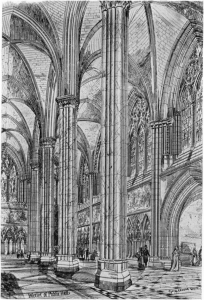

Street’s vision for the New Law Courts was a form of Gothic Revival. In a book he published about Italian architecture, he characterised Gothic architecture by its ‘love of variety’ and ‘idea[s] of life and motion.’ 2 He hoped that his own and other English architects’ Gothic work would be marked by an ‘exaltation of their religion,’ faith being an element he thought the Gothic was especially able to evoke—a perhaps unsurprising comment from Street, considering the majority of his architectural work was on churches.

George Edmund Street’s design, Courts of Justice, 1867, bird’s eye view. From Port: “The New Law Courts Competition”

A current look at the Royal Courts of Justice. From Wikipedia.

Street was not alone in his reverence for the style, despite it going out of fashion only a few years after the New Law Courts’ completion. In fact, despite the Courts of Justice Commission deliberately choosing a representation of Gothic and non-Gothic architects, every single competitor in the New Law Courts competition entered a Gothic-inspired design. Even architects like Henry F. Lockwood, who were more experienced and fond of the Classical tradition, agreed the new legal building would be better suited to the Gothic style.

Because every competitor submitted a neo-Gothic design for the Courts bid, regardless of their previous stylistic tendencies, the atmosphere on the Strand may not have been noticeably different if another architect had been selected.

George Edmund Street’s design, Great Hall, Courts of Justice, 1867. From Port: “The New Law Courts Competition”

A current look at the Great Hall, Courts of Justice. From Londonist.

Perhaps it is because legality and morality seem to go hand-in-hand that every competitor chose a Gothic Revival style for their design. Just as Street saw a particular reverence for religious faith in the Gothic, other scholars have noted the peculiar suitability of Gothic Revival architecture for the Victorian period, a time in which English culture especially emphasized ethical doctrine.3. The Victorian Gothic, ‘primarily an ecclesiastical mode,’ appears to have been well-suited for a building meant to stand for legal, and perhaps therefore moral, righteousness.

Street never was able to see whether the New Courts project fulfilled his intentions for it to be evocative of ‘life and motion,’ ‘variety,’ and ‘faith.’ He died just a year before the Courts’ completion in 1882. The tensions that pervaded the Courts competition seemingly never went away, amounting in undue pressure on Street as he oversaw work on the Royal Courts of Justice. Another competitor (and Street’s former employer), George Gilbert Scott, lamented the ‘bullying and abuse’ he saw heaped onto Street in the years that followed the competition. Although it was a stroke that ended Street’s life, his death was thought by some who knew him, including his son, to be hastened by the lengths he underwent to continue working on the Royal Courts of Justice in the face of so much external pressure and discouragement.

The project, which may have ‘cost him his life,’ now stands out as Street’s most eminent legacy, a marker of English law, and an eye-catching monument of Gothic Revival architecture on London’s Strand.

Further reading:

- Port, M. H. “The New Law Courts Competition, 1866-67.” Architectural History, vol. 11, 1968, pp. 75–120. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1568323

- Street, George Edmund. Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages : Notes of Tours in the North of Italy. 2nd ed. London: J. Murray, 1874.

- Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. “High Victorian Gothic.” Victorian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 1957, pp. 47–71. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3825515.

Superb!

[…] not, then, subject to the same architectural processes other notable buildings on the Strand were, such as the lengthy and dramatic competition that decided the architect for the Royal Courts of Just… Bush and Corbett, instead, working together relatively often, developed a relationship that allowed […]

[…] [1] Téa Emily Carter, ‘George E. Street’s Royal Courts Of Justice: Architectural Visions Of The Strand,’ Strandlines, accessed on 25 October 2022, https://www.strandlines.london/2021/03/31/george-e-street-architect-of-the-royal-courts-of-justice/. […]