The Island Churches of the Strand

Posted in 1700-1799, 17th Century, 1800-1899, 18th Century, 1940-1949, Architecture, churches, Medieval, Places, Pre-1700, Strandlines, Strands and tagged with 11th century, 17th century, 18th century London, 9th century, Aldwych, Architecture, Bush House, central London, Christopher Wren, church, churches, city, Danes, History, island, island church, james gibbs, King's College London, London, london buildings, london church, London history, map, medieval, MyStrand, road, Somerset House, St Clement Danes, St Mary le Strand, strand, traffic, Westminster, William the Conqueror

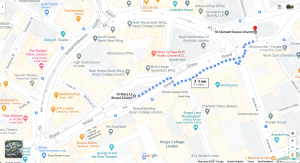

Many King’s students have likely passed the ‘Island Churches’ of the Strand as they make the pilgrimage from Somerset House to the Maughan Library. Likewise, many Strand dwellers may recognise their spires from afar, perhaps unaware of their history. Just a few minutes walk separate St Mary le Strand, located between Bush House and the Strand building, and St Clement Danes, located outside the Royal Courts of Justice. With medieval origins and rebuilt in the late 17th/early 18th centuries, both churches have a rich history and form a unique part of the Strand as they stand amongst the roaring traffic.

St Clement Danes

Origins

The original site of St Clement Danes can be traced back to the 9th century, with the church linked to the Danes and their occupation of London by multiple historical hypotheses. The Parish explains that “Danish settlers who had married English wives were allowed to settle in the area, taking over a small church dedicated to St Clement, the patron saint of mariners”, leading to the church becoming known as ‘St Clement-of-the-danes’.1 Other accounts suggest that the village of ‘Ealdwic’ or ‘Aldwic’ – later known as Aldewych – was largely colonised by Danes and the nearby church was merely named after them, rather than being entirely taken over.2

Source: St Clement Danes Church

Reconstruction

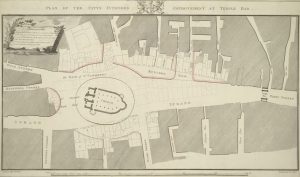

Source: Robert Metcalf, ‘Plan of the Citys intended improvement at Temple Bar’, British Library (1810), Engraving.

William the Conqueror rebuilt the church in the 11th century but it was left to decay. Although medieval St Clement Danes survived the Great Fire of London in 1666, it was in a terrible state and Christopher Wren was commissioned to rebuild it entirely by 1682. James Gibbs later added the finishing touches to the steeple. Wren treated the church as a basilica, translating medieval arrangements of nave and aisles into classical interpretations in which a ‘barrel-vaulted central space was flanked by arcades carried on columns’.3

However, in May of 1941, the church was bombed and only the outer walls and tower remained. St Clement Danes would remain abandoned until 1958. Following public appeal, it was restored and re-consecrated as the central church of the Royal Air Force in the presence of Her Majesty the Queen and HRH Prince Phillip.

St Mary le Strand

Origins

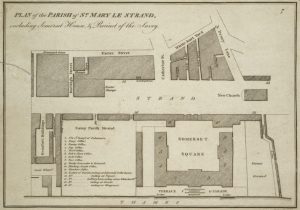

Source: William Simpkins, ‘Plan of the parish of St. Mary le Strand, including Somerset House, & precinct of the Savoy’, British Library (1790), Engraving

Like St Clement Danes, St Mary le Strand may have taken the name of what once stood in its place. A survey of Westminster by John Thomas Smith dates ‘the parish church of the Nativity of St. Mary and the Innocents, in the Strand’ back to at least 1376, under rector William Wynningham. There are also records of a church of the Holy Innocents in Westminster, which Smith supposes is really the same church as St Mary and the Innocents, on the south side of the Strand.4

The original St Mary and the Innocents was pulled down in 1549 so that Somerset House could be built.5 The parishioners were promised a new church, but this was not fulfilled until much later and they had to join the church of St Clement Danes, followed by the chapel in the Savoy.6

Reconstruction

James Gibbs built St Mary le Strand between 1714 and 1717 under the Fifty Church Act of 1711. The church now stood on an island, on the north side of the Strand and opposite Somerset House. The site chosen was ‘the most prominent of any awarded by the commissioners’ and generated a lot of interest; this made it an ideal project to grow the budding architect’s career. The church was originally designed to make the most of Queen Mary’s regular use of the processional route from St James’ Palace to St Paul’s and the City, with its east and west sides reflecting motifs from St Paul’s Cathedral while its north and south facades were inspired by the festive scenes and theatrical spectacles of the royal procession.

However, Queen Anne passed away before the church’s completion. Her Hanoverian successor did not make such use of processions, estranging the architecture of St Mary le Strand from its original purpose. Still, John Erskine, twenty-second Earl of Mar, called the finished church ‘his fair daughter in the Strand […] the most complete little damsel in town’.7 Since 1982, St Mary le Strand has been the official church of the Women’s Royal Naval Service, the Women’s Royal Naval Reserve and the Association of Wrens.8

Source: ‘Somerset House and the New Church, Strand’, 1809, Aquatint with etching, coloured, British Library, King George III Topographical Collection

Then and now…

There were complaints at the time, like today, on the busy traffic surrounding the two churches. Buses stop and go and cars beep as they overtake bicycles. The hustle and bustle of central London does not stop for religious services.

St Clement Danes and St Mary le Strand are enmeshed with the movements of London, entangled in the messiness of the Strand. To its pollution, to its walkers. Yet, as they stand tall, imposing and silent amongst this roar, they remind us of the street’s long history.

Of a time when the ground they stand on was merely part of a small village.

Next time you walk along the Strand, past the island churches, notice the stillness they offer. A pause in the middle of London’s busiest flow. The clear sound of their bells ringing is but one of the Strand’s reminders to appreciate where we stand.

- ‘History’, St Clement Danes Church <https://stclementdanesraf.org/history/>

- Robert L. Whytehead, ‘“The Lesse Set By”: an early reference to the site of Middle Saxon London’, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 55 (2004), 27-34 (pp. 29-30)

- Adrian Tinniswood, His Invention So Fertile: A Life of Christopher Wren (London: Jonathan Cape, 2001), pp. 203, 219

- John Thomas Smith, Antiquities of Westminster: The Old Palace, St. Stephen’s Chapel (Now the House of Commons) &c. &c.: Containing 246 Engravings of topographical Objects, of which 122 no longer remain: This Work contains Copies of Manuscripts which throw new and unexpected light on the Ancient History of the Arts in England (London: R. Ryan, 1807), pp. 5, 89-90

- John Slater, ‘The Strand and The Adelphi: Their Early History and Development’, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 71.3654 (1922), 19-32 (p. 27)

- London Parishes: Containing the Situation, Antiquity, and Re-building of the Churches Within the Bills of Mortality (London: B. Weed, 1824), p. 152

- William Aslet, ‘Situating St Mary-Le-Strand: The Church, the City and the Career of James Gibbs’, Architectural History, 63 (2020), 77-110 (pp. 77, 102)

- ‘About us’, St Mary le Strand <https://stmarylestrand.com/about-us>

[…] will notice many key elements of the Strand on these close-ups of the map. Temple bar, St Clement Danes, Somerset House, the Savoy Wharf (just south of the soon-to-be built 1886 Savoy Hotel), and […]

Thank you for this piece, Marion. These churches are lovely oases amidst a whirlwind of motorists, cyclists and pedestrians. Once inside the rush of life is calmed and time seems to stand still; one can gather oneself, reflect and get fortified to face the rest of the day with joy!

[…] let Peter’s recent arrival misguide you, he knows St. Mary’s and the Strands’ history very well! As part of our conversation we have a special bonus video […]

[…] In medieval London there were ‘more churches than in any other city in Europe and more than a hundred churches within the walls of the old City.’[3] Today, in the Temple area of the City, there are three churches: St Mary Le Strand, St Clement Danes, and the well known Temple Church. The first two date from the late 17th/18th centuries and are located in the middle of the Strand main road). […]

Excellent. Reading this after the heaven-sent pedestrianisation of the road around the church of St Mary le Strand