Speculation and Urban Planning after the Great Fire

Posted in 17th Century, Architecture, Strandlines and tagged with

In the wake of the Great Fire of London (September 1666), many speculative entrepreneurs reinvented themselves as urban developers. These individuals were the major figures of the modernisation of London’s street network. Laying out regular streets over freshly-bought land and building rows of similar (if not identical) terrace houses proved the best way to maximise profit [1].

The boom in street planning was essential in transitioning from a medieval arrangement to a modern urban fabric, and developing new areas such as the Strand where land was cheaper and more available than further west. The foremost of these investors was Nicholas Barbon (1638-98), who acted in many local-scale projects: South of the Strand, Red Lion Field, Chancery Lane, Lincoln’s Inn, Temple area, and more – all of which still remain in place today and are direct neighbours to the Strand [2].

Essex Street, to the immediate west of Middle Temple, has seen all of its buildings remodeled through the centuries. However, its topography remains unchanged with its slope towards the pre-Victorian banks of the Thames. The seventeenth-century watergate is still present (on that topic also the York Watergate), and acts as a visual reminder of the colossal work undertaken by Joseph Bazalgette at the time of construction of the Victoria Embankment in 1865.

Essex St. (or rather its non-existence) before Nicholas Barbon (1676)

Essex St. before Sir. Joseph Bazalgette (1746)

Essex St. as it appears today following the creation of Victoria Embankment (1893)

But in the seventheenth century, Barbon wasn’t without his critics. His “continued aggressive expansionary speculation” attracted legal disputes; but ended up as a major driving force for the urbanisation of London, especially in connecting its two centres, the City and Westminster, through the Strand. Similar impulses in construction include the Grosvenor Estate at Oxford Circus, Bloomsbury and Marylebone by the Bedfords (who were keen promoters of “streets and squares of orderly, well-built houses”); or, later in the century, Islington, Paddington, and Regent’s Park.

Despite being the perfect opportunity to conceive a grand urban plan, the Great Fire of London had very little impact on the street arrangement in the City of London. Indeed, the state of urgency in which bankers and merchants found themselves after the catastrophe prompted a faster rebuilding on the medieval street pattern — with the interdiction of timber exteriors, a new limit to the height of houses, and a widening of the main roads.

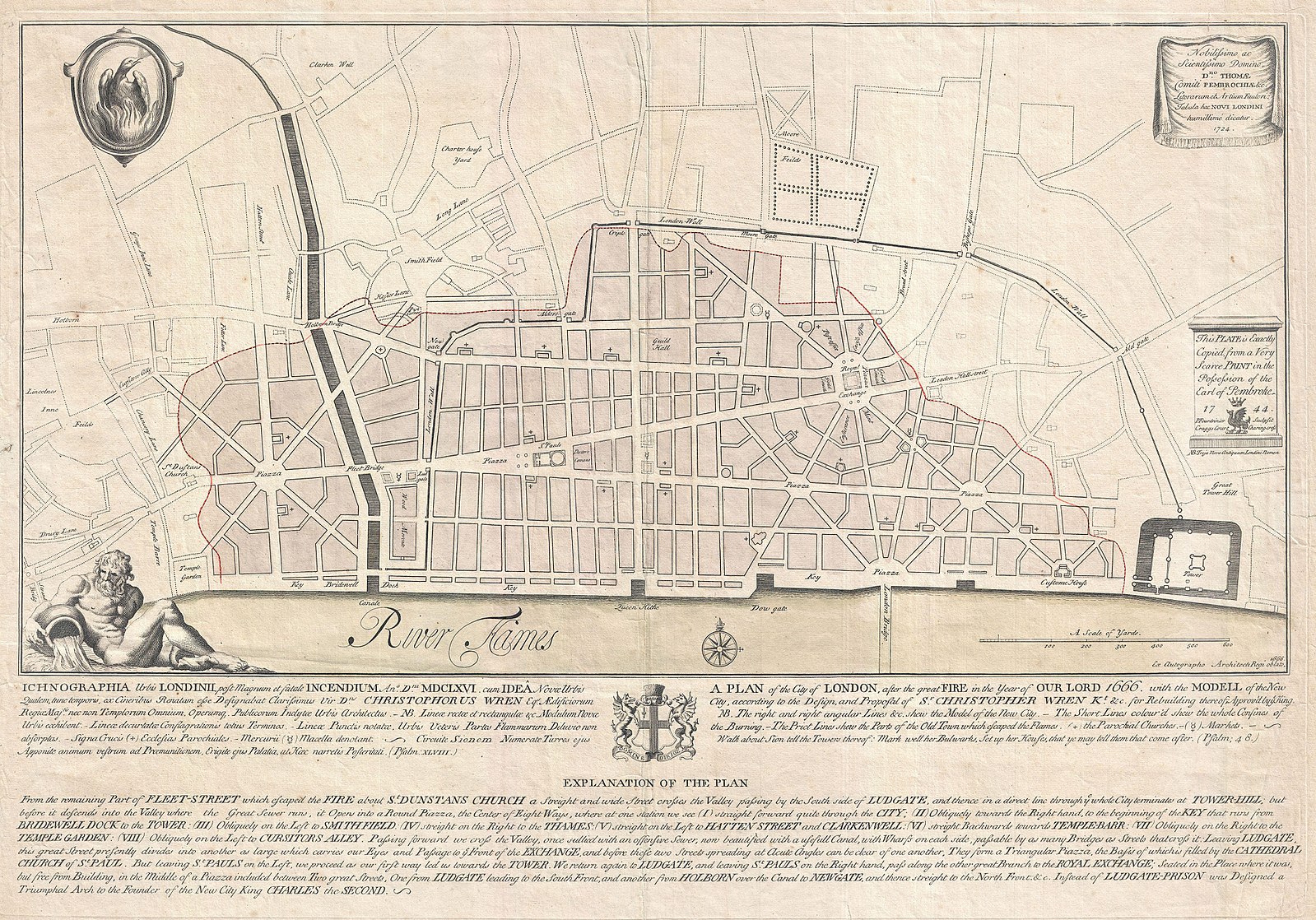

Famously, the grand, ordered and dignified plan proposed for the City by Sir Christopher Wren in 1666 contained his wish for “pomp and regularity”. Rumour says it was to the liking of Charles II who dreamt of “a much more beautiful city than at this time consumed”, but was quickly forgotten due to the aforementioned urgency of rebuilding, and lack of money in a time of war against the Dutch Republic. Even if unfeasible because of its overlooking of topography (ignoring hills and rivers, for instance), Wren’s plan contained some remarkable ideas that would effectively be adopted during the nineteenth-century reconstruction of Paris: wide avenues, converging axes, scattered squares, and radial layouts around important locations. [3]

Sir Christopher Wren’s plan for the reconstruction of the City

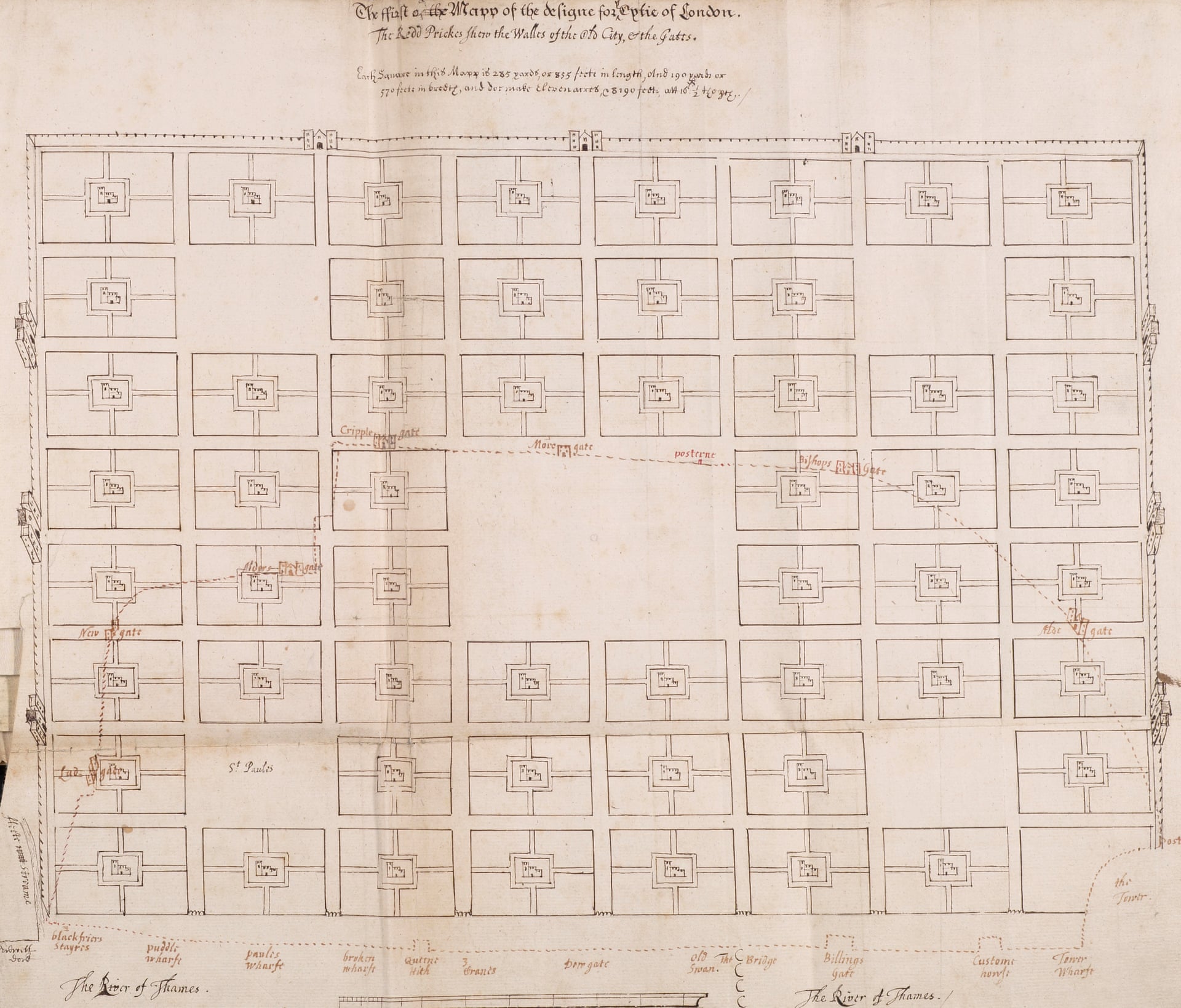

Other designers proposed even more regular plans, all based on the gridiron system — in a manner quite familiar to new cities in America — including one plan attributed to Robert Hooke (a physicist, and later Wren’s architectural assistant) and Richard Newcourt (a cartographer, cf. his 1658 map). Newcourt even went as far into the rationalisation of city life as to place a church within each block. [4]

Robert Hooke’s seventheenth-century plan (inset) in contrast to the reconstructed medieval street network.

Richard Newcourt’s plan, showing a church in every block.

In hindsight, and even ignoring the lack of topographical considerations, these almost-mathematical plans for the rebuilding of the City seem ill-advised. It is precisely the disorder of its streets that have made the City a fertile ground for architectural experimentation; sticking to the medieval urban pattern allow the picturesque multiplication of lines of sight and the juxtaposition of styles we know and love in the Square Mile.

Walbrook, in the City of London

Take for example this snapshot of Walbrook, the artistic and economic history of the City of London can be felt (if not read) in the close proximity of Sir. Christopher Wren’s 1679 Baroque St. Stephen Walbrook, George Dance’s 1752 Palladian Mansion House, John Whichcord’s 1873 High-Victorian National Safe Deposit, and Norman Foster’s 2010 Neomodern Walbrook Building.

Such a characterful view could not be imagined in the well-planned streets of Belgravia, Mayfair, or Pimlico; where the beauty comes from the homogeneity, and would be disturbed by any out-of-style addition. And it is perhaps this balance between the uniformity of residential areas and the architectural colourfulness (which would have been stopped by the post-Fire great plans) of the beating heart of the City that makes London as beautiful as it is today.

Sources:

[1] Ann Saunders, The Art and Architecture of London: An Illustrated Guide, Phaidon, 1984 (pp. 11-22)

[2] James Stevens-Curl and Susan Wilson, The Oxford Dictionary of Architecture, Oxford University Press, 2016 (3rd Edition)

[3] Adam Forrest, How London might have looked: five masterplans after the great fire of 1666, The Guardian, 25 Jan 2016

[4] Royal Institute for British Architects, Creation from Catastrophe – How Architecture Rebuilds Communities, Exhibition, 2016