Shops on the Strand: women in business in early modern Westminster, 1600-1740

Posted in 1700-1799, 17th Century, 18th Century, Places, Retail, Strandlines, Strands, people, shops, workers and tagged with London history, New Exchange, Women, commerce, fashion, history of fashion, research, seventheenth-century, women's history

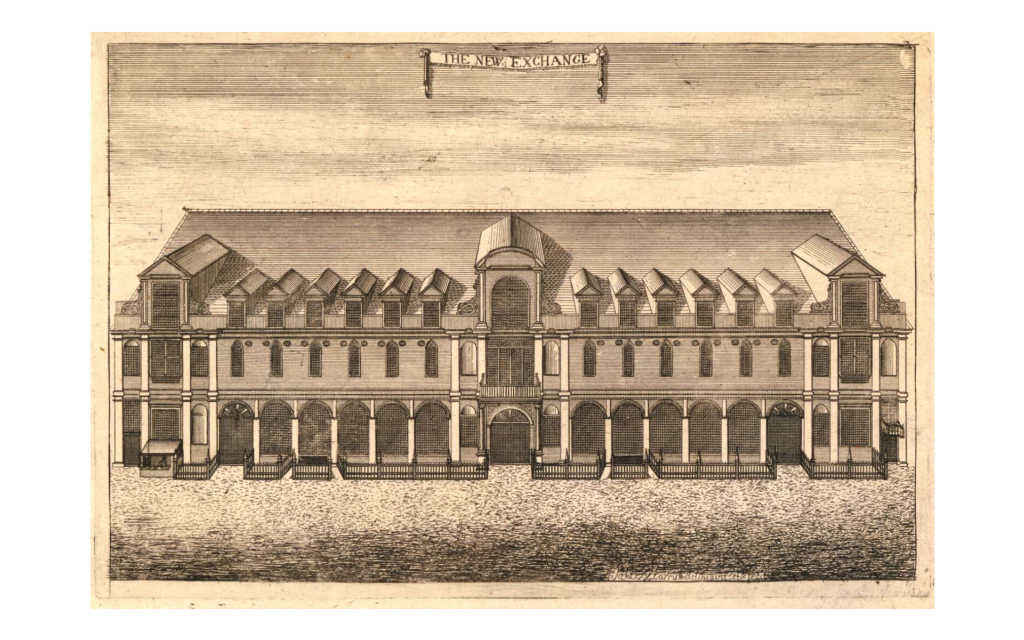

In October I began work in earnest on a new research project, which will illuminate the lives of women in business on the Strand in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. I am particularly looking forward to uncovering all sorts of material on the myriad shops in this location, whether at street level or in the early shopping centres of the New Exchange (pictured below), the Middle Exchange and Exeter Exchange. This will provide new insights into the social, economic and cultural history of the area, helping us to imagine what the Strand was like in the past, and how it has changed over time.

View of the front of the new Exchange, or Britain’s Bourse, in the Strand. c.1715. Engraving. Print made by John Harris. From the British Museum collection.

My research is funded by the Women’s History Network and it will allow me to further develop material already contained within my PhD thesis, entitled ‘A Fashionable Business: Seamstresses, Mantua-makers, and Milliners in Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century London’. One of my thesis chapters explored the locations of women’s businesses on particular streets including Borough High Street, Cheapside, Bishopsgate Street and the Strand and I found that focusing on a specific location was an effective way of bringing together multifarious sources in order to place people and their work in context.

I decided to focus on the Strand between 1600 and 1740 because I want to understand how and why this busy thoroughfare transformed over time. I’d particularly like to explore the boundaries between the City and Westminster. Were there differences in the occupational structure of the Strand and the surrounding area when compared to more established high streets like Cheapside in the City of London? What trades in particular proliferated there?

So far, I’ve identified numerous seamstresses, milliners and tyrewomen (retailers of women’s clothing and accessories to adorn women’s coiffures) working in the New Exchange, which was built in 1609 and demolished in 1737, thereby fitting neatly into the time period under review. This balance of trades is directly comparable to the Royal Exchange, which was and still is (though it has burned down twice) at the heart of the City on Cornhill/Threadneedle Street, so tracing the connections between these two locations will be useful for understanding retailing in London and the wider metropolis. Yet, the Strand had the advantage of being near the court at the Palace of Whitehall and, later, at St James’s Palace: so another question is how did this alter the socio-economic character of Westminster, and how was trade affected during the Interregnum?

I’m developing a walking tour as part of this project. Developing a tour offers useful opportunities to share my findings and to compare the present-day Strand to the Strand of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Any tour fundamentally has to take the current architecture into account whilst endeavouring to bring the past to life. Key buildings that are a focus of my study have been demolished and replaced by new landmarks and establishments. For example, the Exeter Exchange, demolished in 1829, is now the site of the Strand Palace Hotel. A bit of imagination will therefore be required to envisage these imposing long-lost structures.

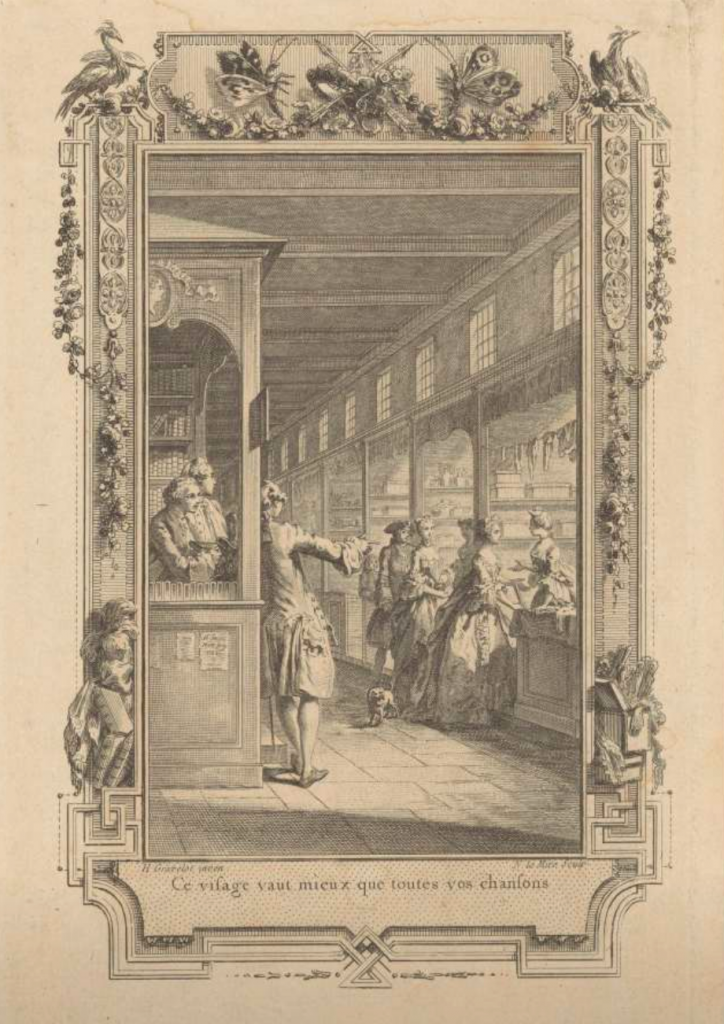

Yet, in many ways the Strand still retains its historic character, particularly in the variety of public houses and shops available to passersby. Likewise, complaints by residents and business owners seem reassuringly familiar. Traffic was felt to be an issue even in the seventeenth century and a petition to the House of Lords dated 1648 from shopkeepers in the New Exchange and other inhabitants in the Strand complained that they were ‘much prejudiced and annoyed by a multitude of hackney coaches that are continually standing in, and pestring the streetes thereaboutes’. (Parliamentary Archives HL/PO/JO/10/1/252, see British History online for full transcription). One of the signatories of this petition was Mary Turpin, a shopkeeper on the New Exchange who married George Dobson that same year (LMA P69/MIC5/A/001/MS05142). An engraving by Hubert François Gravelot allows us to visualise Mary Turpin’s shop, providing an example of the kinds of stalls or booths within comparable shopping centres. Each stall was constructed from wood and contained boxes and shelves used to store all kinds of valuable wares from lace and pins to buttons, feathers and handkerchiefs.

Galerij van het Paleis van Justitie te Parijs, Noël Le Mire, after Hubert François Gravelot, 1744 – 1774. From the Rijks Museum collection.

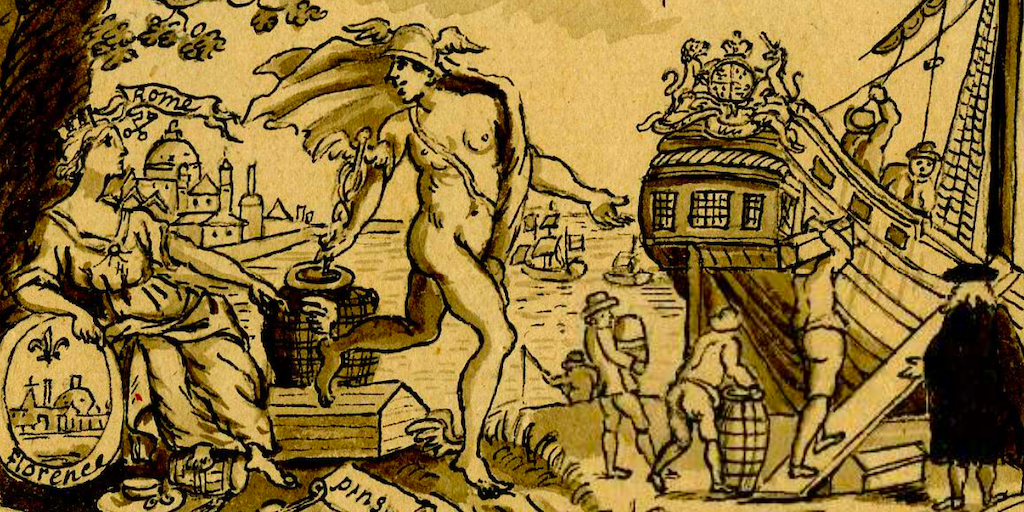

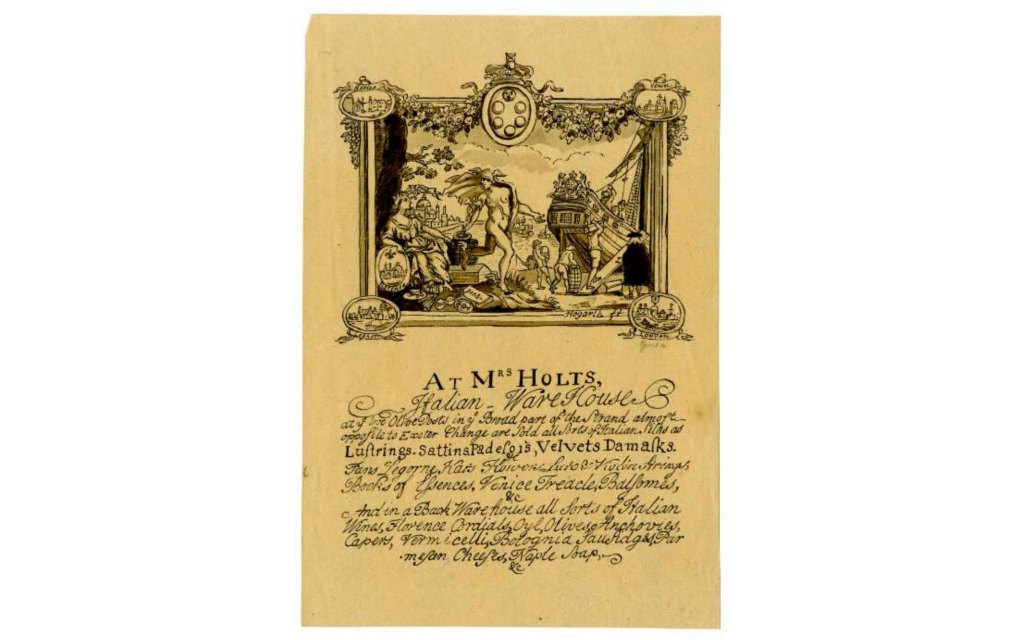

Surviving printed ephemera also offers a fascinating glimpse into the availability of imported goods from Europe in the early eighteenth century. A trade card engraved by William Hogarth for Mrs Holts’ Italian Warehouse shows that it was situated at The Two Olive Posts ‘almost opposite the Exeter Change’, and that she sold a vast array of Italian goods, everything from silks and velvet damasks, to violin strings, parmesan cheeses, wines and fans.

Copy of a trade card for Mrs Holt’s Italian Warehouse, after William Hogarth. From the British Museum collection.

The widow Cressett advertised in The London Journal that she sold mineral waters ‘By order of the Master of the Bath and the Pumper, and also of the Master of the Hot Well of the Bristol Waters’, and that ‘she hath them fresh every Wednesday and Saturday’ from her shop called the Two Golden Sugar Loaves in Charing Cross (The London Journal, CLXXVII, 15 December 1722. Available through: Adam Matthew, Marlborough, Eighteenth Century Journals, accessed 10 October 2020). Both of these examples demonstrate female-led entrepreneurship and the provision of luxury goods to Londoners and visitors to London alike.

The above examples show that information on the Strand can be found in online sources either via the wonderful resources from The Power of Petitioning Project on British History Online, museum collection databases or databases of digitised eighteenth-century journals. Though the year 2020 has presented some unique difficulties for researchers, I have been impressed by how dedicated those working in archives, libraries and museums have been in order to provide as many resources as possible. I’ve certainly learned to be more open in how I approach my research and also to take better stock of what resources I have available already. I was very lucky to receive an Adam Matthew Digital Collections Subscription from the Royal Historical Society in July and this has proved extremely useful for uncovering information from printed sources so far. However, I am still very much looking forward to visiting the London Metropolitan Archives in person very soon to embark on some more sustained research tasks with manuscript sources.

Though I’m still in the early stages of this project, I will be working towards publishing my research either as an article in a journal or perhaps even developing it into a book in the future. I aim to have a downloadable walking tour available by summer 2021.

For any readers wishing to keep up to date with the latest news on my project, please visit my blog at: https://afashionablebusiness.wordpress.com.

Fascinating!

I am a City of Westminster Tour Guide and would like to know more about your walking tour. I’d be delighted to go along with you one day – either by Zoom or by foot.

Thank you for reading, Pernille!

We’ve put links to Sarah’s blog at the bottom of this post, so do follow her there as she’ll announce tours there first. Of course, we will also try and spread the news!

Fran – Assistant Editor

A very valuable resource! Thank you for making it.

If you ever come across a reference to George Heriot in the Strand (ca 1610) I’d be very interested..

I know he had a house there and probably conducted his business as a jeweller and goldmith there.