The Adelphi and Robert Adam

Posted in 1700-1799, 18th Century, Architecture and tagged with adelphi, Architecture, construction and demolition, design, eighteenth century, Westminster

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Strand had become the theatre of one of London’s most adventurous architectural enterprises: the Adelphi. Four Scottish brothers Robert, John, James, and William Adam endeavored to transform a slum into a fashionable quarter, and in doing so, to promote their dream of social and artistic uniformity, equity, elegance, and daring. Let us now explore how this dream started, took form, and how it ended…

– History –

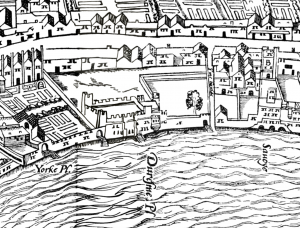

Durham House on the Agas Map of the 1560s

The story of the Adelphi begins in 1768, when the four brothers Adam take the lease for the site of a former episcopal palace, Durham House. Built for the bishop of Durham in 1345, it had been confiscated and resold by kings and queens several times. Part of the estate, Durham Yard, also suffered a fire in April 1669, as recalled by Samuel Pepys in his diary [1]:

“I am told by Betty, who was all undressed, of a great fire happened in Durham-Yard last night, burning the house of one Lady Hungerford, who was to come to town to it this night; and so the house is burned, new furnished, by carelessness of the girl sent to take off a candle from a bunch of candles, which she did by burning it off, and left the rest, as is supposed, on fire. The King and Court were here, it seems, and stopped the fire by blowing up of the next house.”

However, while the house was in poor condition, its location (and indeed the whole Strand) had become a valuable area for business, as reflected in the establishment in 1609 of a fashionable venue for shopping: the New Exchange. Built by Inigo Jones, it was Westminster’s answer to the City’s Royal Exchange, and became a popular shopping location with the development of Covent Garden market and the burning of the Royal Exchange in 1666 [2]. Jones’s development came to represent the gaiety and humour of the Restoration, as well as being a sociable place to be seen in. The Grand Duke Cosmo of Tuscany described it:

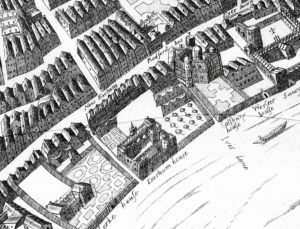

New Exchange on Newcourt’s 1658 Map

“The building has a facade of stone, built after the Gothic style, which has lost its colour from age and become blackish. It contains two long and double galleries, one above the other, in which are distributed in several rows great numbers of very rich shops of drapers and mercers filled with goods of every kind, and with manufactures of the most beautiful description.”

After gradually losing its importance, the New Exchange was shut down in 1737 and the area progressively deteriorated. The Adams understood, however, the potential of the Durham estate and set in motion their grand plan of “covering the dilapidated and forlorn area of Durham House Estate with buildings of magnificent and harmonious scale”. As a way to put into stone their quest for unity, they derived the name of their enterprise from the Greek for brothers: ἀδελφοί: Adelphi.

– Architecture –

To quote Nikolaus Pevsner, it is hard to visualise now what the Adelphi looked like and what it meant [3]. Regardless, let us try!

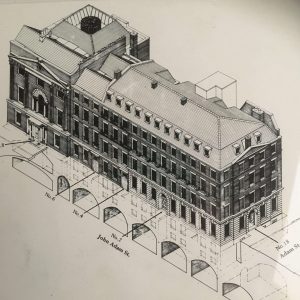

The grandeur of the Adelphi sprung from its imposing dimensions and homogeneity: its forty-one bays were fully visible from the Thames, making it the “first great river-side composition in London”, and the two left and right pavilions proved to be the perfect accent to the whole, with their doubled pilasters (flat, rectangular, decorative columns) and garlanded pediments.

Benedetto Pastorini’s engraving of the Adelphi terrace in its splendour. The arches were at direct contact with the Thames until the mid-19th century and the construction of the Embankment.

Cross section of the Adelphi structure, highlighting the supporting arches.

From the river, one could also have appreciated the engineering effort behind — or rather, below — the Adelphi. To compensate for the slope of the terrain, going down towards the river, the Adams built a series of large arches to support the Adelphi terrace. These vaults, rented by the brothers to the government to help finance their project, soon took on a strong presence in the London imaginary, as Dickens shows in David Copperfield (Chapter 11):

“I was fond of wandering about the Adelphi, because it was a mysterious place, with those dark arches. I see myself emerging one evening from some of these arches, on a little public-house close to the river, with an open space before it, where some coal-heavers were dancing; to look at whom I sat down upon a bench. I wonder what they thought of me!”

The way Robert Adam (the foremost architect of the brothers) highlights the external and central bays without downplaying the others shows great talent: it is the finesse of the ornamentation, not its exuberance, that strikes the visitor. Robert Adam cultivates an architecture of restraint — by, for example, preferring the pilaster to the column, by refusing to add a wide triangular pediment over the central bays, or by limiting the plaster ornaments to delicate honeysuckle motifs on the pilasters and the frieze.

– Robert Adam and Palladianism –

I’d suggest that the key to Robert Adam’s talent is found in his two main influences, and how they combine and conflict: Roman design, and the architecture of Palladio. English Palladianism enjoyed a hugely popular flourish over England in the eighteenth century, with its respectful modernisation of Antiquarian architecture, derived from Andrea Palladio’s sixteenth-century example.

For more than 100 years, Palladianism was the only style that most architects would even consider. Its main features are harmonious proportions, monochrome exteriors, limited decoration, frequent pediments, and symmetry. In a way, Palladio approached antique architecture with a certain minimalism.

Interior room of Headfort House (Ireland) in Robert Adam’s signature style

Robert Adam’s Apsley House in London in a most Palladian style

Despite personal distaste for Palladianism (calling it “ponderous” and “disgustful”), Robert Adam had to bow before the taste of the day and compose with it. However, he did so by trying to incorporate elements of the other great influence on his art, Roman designs. Drawing from his experience on ruins (most notably Diocletian’s palace in Split), he progressively introduced more antique accuracy in the decoration by reinterpreting and combining archeological motifs in Palladian buildings. This “diversity of forms” was core to his artistic philosophy and finds echoes in the Picturesque quality to his works. As Nikolaus Pevsner put it:

“Compared with contemporary architects in France, Germany, or Italy Robert Adam remained a Palladian throughout his life. But compared with the style of the English Palladians before and around him, his was all the same a revolution.” [3]

Robert Adam’s 1764 engraving of the ruins of the Diocletian Palace in Split (Royal Academy)

– The end of the dream and the Aldephi today –

Very rapidly, the Adams’s endeavour met its financial failures, with the brothers having to obtain from George III the right to organise a lottery to sell the estate and avoid bankruptcy — an attempt vilified by Horace Walpole in July 1773: ”What patronage of the arts in Parliament, to vote the City’s land to these brothers, and then sanctify the sale of the houses by a bubble!”.

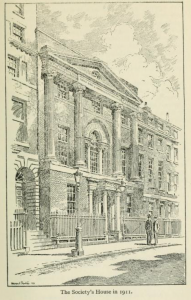

Adam’s Royal Society of Arts building in 1911 (notice the ressemblance between the central window here and the right arcade on Adam’s engraving of the Diocletian palace)

The Victorian era showed little regard for the building, which fell in a terrible state and began to look dated compared to the new and modern Savoy and Cecil Hotels. By the end of the 1920s the decision had been made to destroy the Regency masterpiece; it was later replaced by a large Art Deco complex in 1936.

Today a few relics remain. The streets around the Adelphi area, laid out at the time of the construction, bear the names of the brothers (Adam St., Robert St., and John Adam St. may still be found; while William and James Streets have disappeared). Some of the vaults are still visible from Lower Robert Street. Across the Strand, a theatre bears the name of the project since 1819. And last but not least, the building housing the Royal Society of Arts has remained untouched, with its exquisite proportions; built by Adam in 1772-4 it includes a hall, a lecture rooms, a library, and some accommodation — all in the finest Adam’s style. [4]

Perhaps the success of the “bold Adelphi” (as Mason wrote in 1773 to the enemy of Robert Adam, Sir William Chambers [5]) is hard to judge today. Its premises and flair have been almost entirely forgotten. But few buildings have managed to inject a simple objective – “Transforming a slum into a fashionable quarter” – with a singular artistic style, elegance, and engineering prowess, with such grandeur.

Perhaps, finally, the legacy of the Adelphi is best read in the life of the small boy living in the slum of Buckingham Street, who watches with marvel the forest of dark arches by the riverside, and who ends up later in life sitting in the delicately painted meeting room of the Royal Society of Arts, sharing his past memories in David Copperfield…

Arches under the Adelphi terrace before their destruction, 1920s

Sources and further reading

[1] Samuel Pepys, Diary, Entry for 26 Apr 1669 (accessible at https://www.pepysdiary.com/diary/1669/04/26/)

[2] Mark McDayter, The Royal Exchange and the New Exchange (accessible at https://instruct.uwo.ca/english/234e/site/bckgrnds/maps/lndnmpexchng.html)

[3] Nikolaus Pevsner, London I: The Cities of London and Westminster (1962), p. 343.

[4] Particulars of the Adelphi Estate, Auction Catalogue, London, 1927

[5] William Mason, An heroic epistle to Sir William Chambers, 1773, v.107

[6] Survey of London, The Rise and Fall of the Adelphi, London, 2017 (accessible at https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/survey-of-london/tag/adelphi/)

[7] G H Gater and E P Wheeler (ed), Survey of London: Volume 18, St Martin-in-The-Fields II: the Strand, London, 1937, pp. 99-102

Very nice piece, thank you Paul

Thanks for reading and commenting, Elizabeth!

– Fran, Assistant Editor.

Incredibly insightful and informative, many thanks Strandlines!

Very glad you enjoyed it Helen!

-Tristan, Editor

Very interesting piece, thanks!

[…] A Londres, leur création la plus célèbre demeure l’Adelphi, (frères en grec). Cet ensemble construit entre le Strand et la Tamise est en grande partie détruit aujourd’hui. Il se constituait d’entrepôts, magasins et appartements d’habitation. Des 24 bâtiments initiaux de 1768/72 restent quelques façades de brique noire et stucs blancs. En revanche, le nom reste accolé à celui d’un music-hall. Les rues Adam, John Adam et Robert derrière l’hôtel Savoye rappellent l’activité de deux des quatre frères. Robert a d’ailleurs laissé une empreinte plus importante en tant qu’architecte et théoricien. https://www.strandlines.london/2020/10/01/adelphi-robert-adam/ […]