Repost from Courtauld Digital Media: Pictures of London in the Age of Social Media

Posted in 21st Century, Places, Public art, public squares, Sculpture, Strandlines and tagged with archive, Charing Cross, collection, courtauld, Courtauld Library, digitisation, instagram, London, MyStrand, National Gallery, Photography, repost, Royal Courts of Justice, social media, strand, Street photography, Trafalgar Square, Westminster

Editors’ note: The Strandlines editors are always scouring for news and research about the Strand area. Below we’re delighted to be sharing a short extract from ‘The Strand Statues’, a piece by Ruby Gaffney, a Courtauld Connects Digitisation Placement student. Thank you to the Courtauld Digitisation team for allowing us to share.

The Courtauld Connects Digitisation project – part-funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund – will make available online over 1.6 million photographs from the Courtauld’s Conway, Laib, and Kersting collections, free for non-commercial use. Find out more about the project here.

Pictures of London in the Age of Social Media

by Ruby Gaffney

The Courtauld’s digitisation project acknowledges that the online world has radically changed who can consume culture, and how they can do so. The collection will no longer be confined to a basement library. By putting the collection online for the public to access for free, its potential reach will span to anyone anywhere, so long as they have internet access. The photographs can be put to more diverse academic purposes, but they can also be browsed recreationally or looked at through a personal viewpoint.

During the time I’ve spent interning at the Courtauld and getting involved in the digitisation process, I’ve been thinking about the digital age and how it has changed the way we both consume and create photographs. Social media means that anyone with access to a smartphone has the ability to take unlimited high-quality photos, a platform to share them, and an audience. I can scroll on Instagram and find endless pictures – it feels like another photographic library, condensed into tiny digital form.

I find a parallel between the Courtauld’s aim of converting older mounted physical photographs into new digital files, and my own aim in compiling this post: to consider the personal photography which now saturates our newsfeeds from family and friends as an accessible new form of artistic expression.

After browsing the Conway library’s many images of London, I went on social media to see how ordinary people today choose to capture the same locations from the collection.

As would be expected, the comparisons show how much London has changed. For example, I barely recognised a photo dated 1963-8 of a few gloomy pillars overlooking the Thames, as Instagram is now full of colourful videos and pictures of this space – now the iconic Southbank skate park. In other comparisons, we can also see increased crowds in the background, more modern vehicles, and advanced lighting and technology: particularly prevalent in images of theatres or galleries, or of Oxford Street.

The comparisons also show changes in what we prioritise in this new medium of photography. Our profiles are intrinsically linked with our identities, so the pictures from social media focus on people to a much greater extent than those from the library. Even if a person isn’t the focal subject of the photo, the image always contains an implicit awareness of the person behind the camera. Unless we post anonymously, no photo is impersonal. What emerges from the pictures in the Conway collection is a series of images of London at a particular time. What emerges in the photos on Instagram is someone experiencing a particular place at the time of posting.

At the same time, however, the impulse to capture and share these London landmarks is felt by both professional and recreational photographers throughout the decades. I spoke to a few Instagram users about their experiences with sharing photography on social media. Responses were varied, but most people shared a feeling that social media has increased, or created, their interest in photography, and inspired them to take pictures of their surroundings. Digitised collections like the Conway library have a similar potential to inspire online viewers.

Charing Cross

Charing Cross, from the Conway Library CON_B04110_F002_003.

CON_B04110_F002_003. The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

Sunset on Charing Cross, by @jaxcov on Instagram.

Image @jaxcov on Instagram.

“There’s so much amazing photography on social media which easily grabs your attention. This definitely makes me want to take better photos of my own!” @jaxcov.

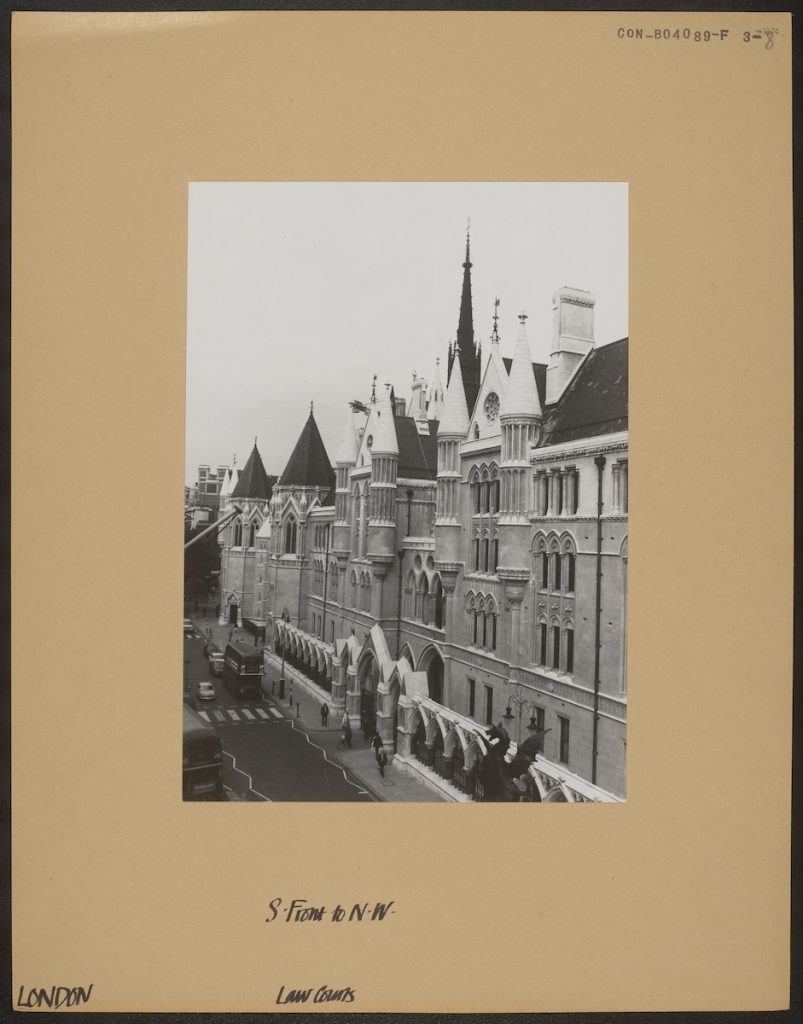

Courts of Law

View of the Law Courts from above, from the Conway Library, CON_B04089_F003_008.

CON_B04089_F003_008. The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

Red bus in front of Royal Courts of Justice, by @ambhout on Instagram.

Image @ambhout on Instagram.

“Social media has made me more interested in photography – it’s hard not to get roped into the constant stream of inspiration. I always wanna try out the things I see online.”

“I have over 4000 pictures on my phone’s camera roll, and probably about 5 times that amount on my computer. I only have physical copies of a tiny fraction of these! I think that’s an exciting thing about my generation: that we have so many images of our lives.”

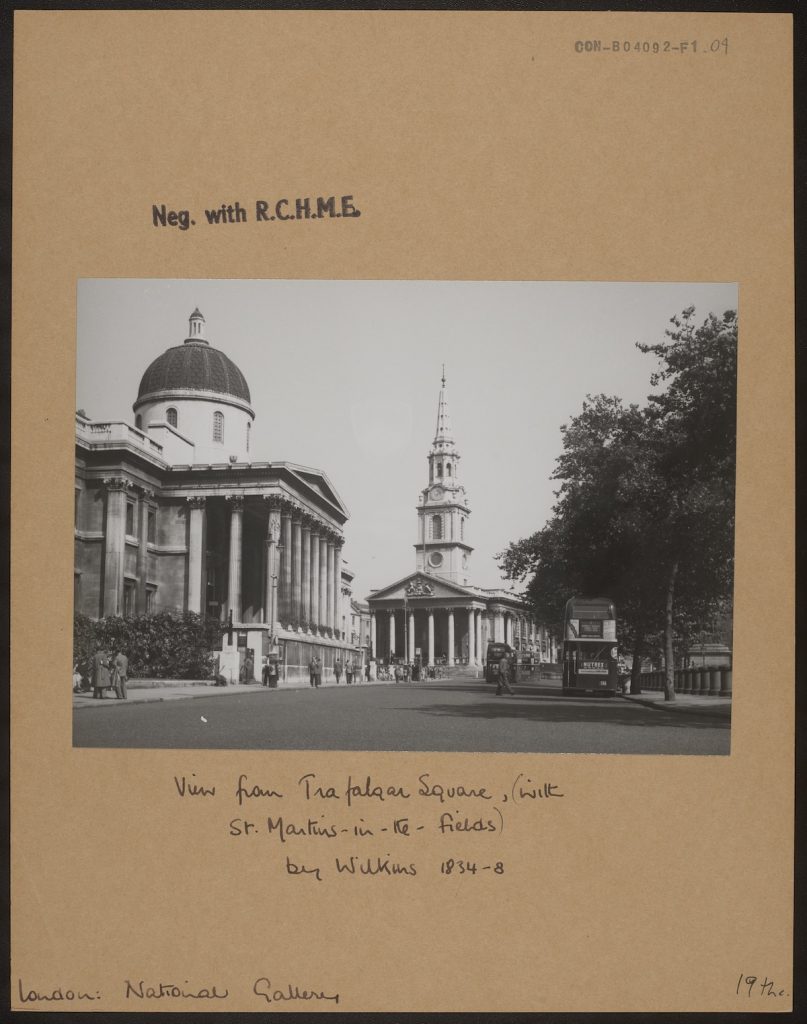

The National Gallery

View from Trafalgar Square, National Gallery to the left, with St Martins-in-the-fields.

CON_B04092_F001_004. The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

The National Gallery, by @kikustralala on Instagram.

Image @kikustralala on Instagram.

“I post what I want, and pay little attention to the likes, follows and comments. When I do look, I find it interesting rather than introverting. In the past I have deleted a photo due to it not getting many likes. But recently I haven’t done that.”

Read more from this post, which explores locations around London, on the Courtauld Digitisation Blog.