Essex street’s Watergate: a threshold to the bourgeois Strand

Posted in 17th Century, Architecture, Pre-1700, Strandlines, Strands, streets and roads and tagged with Architecture, Archway, Barbon, Embankment, Essex street, Intermediary space, London architecture, London history, London old street, old street, Passage, Steps, strand, Strandlines, Street, street planing, The Strand, urban geography, Watergate

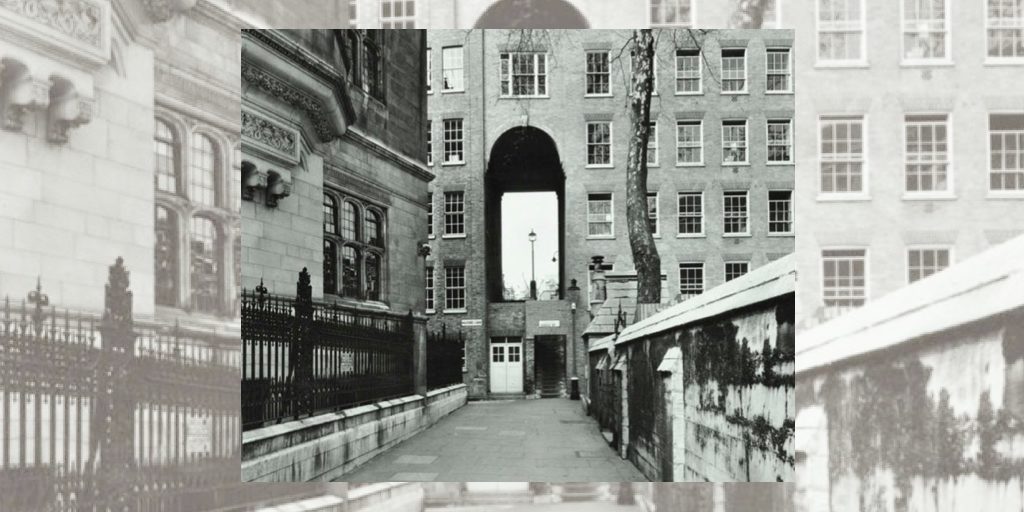

Essex Street Water Gate, London WC2 (1934) Edgar Holloway. The British Museum

“He crossed the road and went into the darkness towards the little steps under the archway leading into Essex Street, and I let him go. And that was the last I ever saw of him.”

– The Diamond Maker by HG Wells (1894).

An “in-between” space, the Essex street’s Watergate closes the street on its southern end and gives access from the Strand to Temple tube station and Victoria Embankment via Milford Lane. Its most distinctive trait is the contrast between the grande nature of the facade entrance and the narrow flight of stone steps and brick doorway below.

This contrast hints at the reason why the Watergate and staircase were constructed by Nicholas Barbon (c.1640 – c.1698) in the 1680s. The developer planned Essex Street on grounds that were formerly occupied by a range of different buildings. Before the Dissolution of the Monasteries (1536 – 1541) by Henry VIII, this space was the home to the Outer Temple, owned by the Knights Templar. This land then became the Bishop of Exeter’s Inn until 1549. At that time, large gardens extended down to the Thames, which was much closer as the Embankment didn’t yet exist.

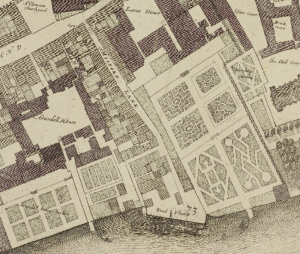

In 1575, the Leicester House was built for Robert Dudley, first Earl of Leicester. It was later renamed Essex House as can be observed on this detail of the 1676 J. Ogilby and W. Morgan’s map of London:

Ogilby and W. Morgan map of London (1676) The British Library

Nicholas Barbon partly demolished the Old Essex House in 1682 to plan the layout of Essex Street with elegant upmarket houses designed to attract the wealthy. Essex Street’s grand Watergate is one of today’s three remaining examples of this form of archway that often accompanied riverside properties. It is conceived as an ornament, a terminate feature for the street to please bourgeois homeowners. It gave access to the riverbank as can be seen on 1682 William Morgan’s Map of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark, while at the same time physically and visually separating the newly developed street from the wharf and warehouses below:

William Morgan’s Map of the City of London, Westminster and Southwark (1682) The British Library

Methuen & Co imprint (1948)

Methuen & Co imprint (1931)

With its fluted Corinthian pilasters and square-headed archivolt arch, the triumphal watergate grew to become a landmark of the Strand. Indeed, it was adopted by 36 Essex Street publishers Muthuem & Co as their logo.

This particular “intermediary space” also inspired authors such as John Gay in his 1716 “Trivia”, that describes the place in a romanticised and grand manner:

“In Milford Lane, near to St. Clement’s steeple;” […]

“Behold that narrow street which steep descends,

Whose building to the slimy shore extends.

Here Arundel’s famed structure rear’d its frame,

The street alone retains an empty name;

There Essex’ stately pile adorn’d the shore,

There Cecil, Bedford, Villiers—now no more.”

However, during the Second World War, the distinctive archway was severely damaged by the bombings, as shown by the 1945 Bomb Damage map:

Bomb damage map (1945) London Metropolitan Archives

Following this, it was restored in 1953 and incorporated into an office building that runs across the end of the street.

In 1970, the Watergate was listed as a grade II building. After being identified as an unsafe frequently used route, the Westminster Council recently took action to light up the staircase, ensuring this micro space continues to serve as a passing point into and out of the Strand.

[…] the end of the Essex Street, there are stairs that go down through like a little archway that leads to the river, which is one of my absolutely favourite spots. I walked through it twice a day and I never get […]