An Edible Utopia under your feet: rhubarb, mushrooms, and more

Posted in Strandlines and tagged with Edible Utopia, Funghi, Gardening, King's College London, London, London by Londoners, Mushrooms, Somerset House, Urban garden, Urban gardening, What's on Westminster, What's on in London, allotment, garderner, park city

*Covid-19 update: many of the events discussed in this article were cancelled due to lockdown. Be the first to know about future Edible Utopia plans by signing up to their newsletter*

“Have you been down here before?” Jane asks me, jangling a huge bunch of keys.

Having met at the entrance to Somerset House, we’ve traversed the courtyard, and, thrillingly, gone through a gate usually locked for visitors. Descending stone steps, the roar of the fountains, tourists’ chatter, and the rumble from the Strand is replaced by the industrial hum of AC units and extractor fans which protrude from Somerset House’s west wing.

What’s behind door number 5? Venturing down to the coalholes with Jane Levi, Edible Utopia.

I’m here in the lightwells and coalholes to explore the fruits of ‘Edible Utopia’, a cooperative project established by Jane Levi, Clare Patey, Tim Mitchell, and Sophie Mason. Writer and researcher Jane met Clare, an environmental artist, and artists and trained organic growers Sophie and Tim at a planning event organised by King’s Cultural Institute and Somerset House Trust for the 2016 Utopia programme at Somerset House.

Jane explains “we had similar ideas and thoughts about food, and how growing, cooking, eating, talking over the dinner table, even doing the washing up are all creative and culturally important and bring people together. Those activities, when they are shared, develop a better world”.

Jane has spent years researching the work of Charles Fourier (1772 – 1837). Fourier was a French writer who had “very specific ideas – some people think he is a bit of lunatic”, about how to use food to create a better life. As Jane herself further explains in articles written for Borough Market blog and the Utopian Studies journal:

“Fourier saw food as the greatest source of personal enjoyment at every stage of our lives. He pointed out that we each have our own tastes, and it should be our life’s work to develop and understand them […] It’s important to know where our food has come from, to understand how to grow it, how to cook it, its place in a healthy diet that works for our own bodies, and how to enjoy eating in happy conviviality.”

That’s why the Edible Utopia project is important to Jane: it’s a “physical manifestation of these ideas”.

Flourishing chicory, planted by the Edible Utopia team.

Somerset House commissioned the Edible Utopia group for its 2016 programme, and the team have been busy growing ever since. However, it wasn’t as easy as installing a few pots around the site, or, indeed, “planting a wheat field on the river terrace – although we’d love to do that one day!”.

Due to listed building regulations, and some local government red-tape, Somerset House has very little space where even a little greenery is allowed. Jane explains as we walk across the courtyard, “men literally come with tools to scrape little bits of moss” from between the paving stones. The solution then, was “we went underground, we went into the hidden spaces”.

Which brings us back to the lightwells and coalholes. Jane shows me around the various buckets dotted along the lower walkway, which in the early autumn were planted with chicory (endive) that now seems to be doing rather well.

The ‘ground level’ ‘roof’: photo taken from the walkway that joins the West and New Wings of Somerset House, with rhubarb pots visible.

Further along the lightwells there is rhubarb. There’s more rhubarb that visitors to Somerset House can more easily see: oddly, at the ground-level join between the west wing and new wing, there is a ‘roof’ of a subterranean part of the building. In the huge, multi-winged, sprawling palace of Somerset House, which joins the Strand at one ‘street level’ and Embankment at a lower ‘street level’, ‘roofs’ and ‘floors’ can seem somewhat interchangeable!

And why rhubarb and chicory? Jane explains that these are both crops that can be developed into specialist produce in darkness: “we’re trying to use permaculture principals, where you work with the plants that can thrive in the space that you’ve got, and then adapt according to what you discover about how the plants respond to the conditions as you go along”. The team are paying attention to where their crop is happiest and noting differences between how the rhubarb on the ‘ground level roof’ grows compared to the plants at various levels of the lightwells.

Rhubarb, happy in the lightwells at Somerset House.

The team didn’t harvest in the first season, “we let the roots grow and get strong over a couple of years, so that next year we can force them” Forcing the plants means bringing them into the dark – that means they grow quickly and elongated, and, Jane explains, “you can get these beautiful pale specimens”.

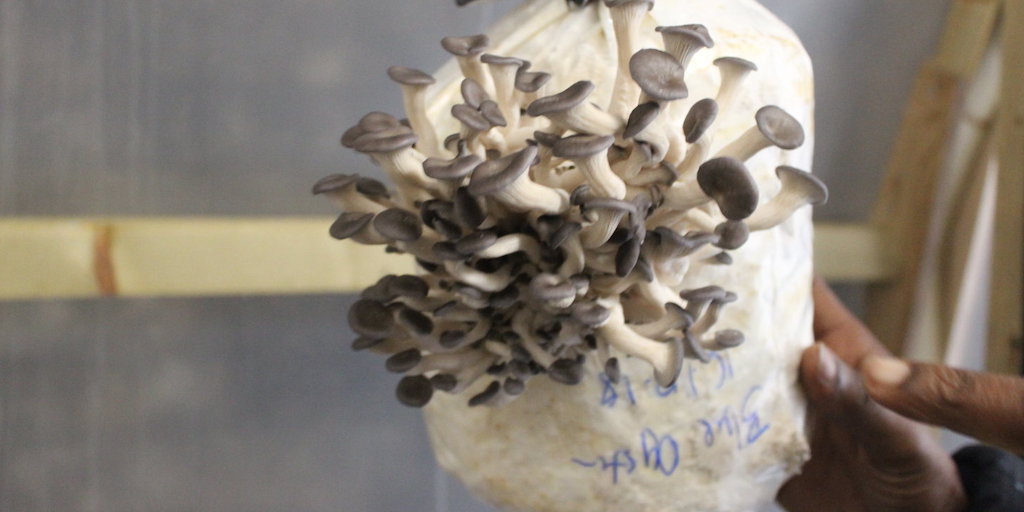

Since its founding, the Edible Utopia cooperative has grown, notably with the addition of mycologist (mushroom expert) Darren Springer, responsible for masterminding the Oyster mushroom-filled coalholes under the fountain courtyard.

Jane shows me into one of the mushroom-houses. Within the stone coalhole, a customised wooden shed structure has been built. Jane explains that mushrooms like a clean, damp but not wet environment, hence the raised floor and plastic lining. The mushrooms sprout from bags filled with coffee grounds and straw (“Ideally it will be just coffee grounds one day”) which hang from the coalhole ceilings or are arranged on shelves. Each bag is “unbelievably productive”: producing up to a kilo a week of mushrooms when in full flow.

The project is developing a (virtuous) cyclical relationship with the restaurants and cafes at Somerset House, which will serve the locally grown mushrooms from February 2020. Used coffee grounds provide the ideal base for Oyster mushrooms, which can then be eaten in the restaurants, before additional kitchen waste is fed to the worms to make soil and fertiliser for the rhubarb and chicory (oh yes, there’s also a wormery in one of the coalholes).

Edible Utopia’s Mushrooms, photo from their project blog.

From the 31 January to the 26 April, Somerset House is staging an exhibition on ‘Mushrooms: the art, design and future of fungi’. Of course, Edible Utopia are involved. They will have an illustrated information point with audio tour in the Seamen’s Hall throughout the exhibition, and the coalholes will be open for bookable tours every month.

As part of the exhibition events programme, mycologist Darren will be discussing the mind-altering properties of mushrooms with Robin Carhart-Harris, Head of The Centre for Psychedelic Research at Imperial College London. Edible Utopia is always part of the Somerset House World Earth Day schedule (the 2018 workshops created the first wormeries) and this year on Saturday 25 April the team will be running mushroom-growing workshops and giving tours of their secret growing spaces, as well as taking visitors to meet its very own earth-creators in the “wormhole”.

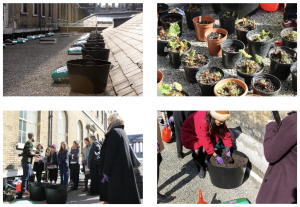

Apart from the Somerset House ‘Mushrooms’ season, the Edible Utopia team are busy growing and planning. The group are “constituted as a co-op as a way of saying we’re open, we want everyone to join us”. They’ve held events for planting, watering, and even singing to the newly seeded plants. Be the first to know about other events throughout the year by joining their mailing list.

Previous events include singing to the rhubarb seedlings. Photo by T Mitchell via the Edible Utopia blog.

Jane hopes that besides hosting an Edible Utopia feast, next year the team will be able to stage events in the Deadhouse, a space that I am only able to glimpse during my visit. This tunnel runs east to west under the fountain court. Its darkness is perfect for forcing rhubarb and chicory by candlelight, and visitors might be able to hear the plants creaking away as they reach for light.

The Deadhouse is so-called as it contains the grave markers of kitchenhands and gardeners who were buried in the old Somerset House palace’s chapel in the seventeenth century. As I peer through the gates, Jane points out her favourite – and one of the team’s historical inspirational characters – the first marker on the left (entering from the west), dedicated to Catherine Guilermet, the ‘femme du potagé de la reine’: the Queen’s kitchen-gardener’s wife, who died in 1633.

Edible Utopia collaborates with other organisations, running sessions for school children, welcoming marginalised groups to Somerset House, and working with St Mungo’s Homeless Charity to deliver mushroom cultivation training to their clients: not only is gardening a valuable skill, but it can provide a great sense of wellbeing.

Previous Edible Utopia workshops, photos my T Mitchell via the project blog.

This is something I can certainly relate to: living in London it’s a luxury to have access to growing space, but no matter whether I’ve been lucky enough to have a garden or a tiny window box, I always try and grow something. A quote by Joyce Carol Oates frequently pops up on gardeners’ forums (admittedly often in a saccharine, cursive, word-art type, but I am fond of it nonetheless): “The gardener is the quintessential optimist: not only does he believe that the future will bear out the fruits of his efforts, he believes in the future.”

For me, the beauty of the Edible Utopia project is not only its optimism and future-thinking, but also the way in which gardening in the spaces of Somerset House is something of a return. The ‘femme du potagé’ and the other inhabitants of the Deadhouse would surely approve.

You can find more photographs and audio clips of our conversation with Jane on our Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. Be sure to check them out on your preferred social media!

Please could someone get in touch with me about “Catherine Guilermet, the ‘femme du potagé de la reine’: the Queen’s kitchen-gardener’s wife, who died in 1633.”

Many thanks

Hi Gillian! We’d recommend you get in touch with the Edible Utopia team, you can find their info here: https://www.edibleutopia.org/contact