Repost from Courtauld Digital Media: Visions of London

Posted in 1930-1939, 20th Century, Architecture, contemporary, future, Places, shops, Strandlines, Strands, streets and roads and tagged with Architectural Drawings, Architectural models, Conway Library, Courtauld Library, design, Glass Age Committee, Maxwell Fry, Plans, Westminster

Editors’ note: The Strandlines editors are always scouring for news and research about the Strand area. Below we’re delighted to be sharing an extract of ‘Visions of London’, a piece by Hannah Wilson, a Courtauld Connects Digitisation placement student. Thank you to the Courtauld Digitisation team for allowing us to share a snippet of Hannah’s longer post. The Courtauld Connects Digitisation project – part-funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund – will make available online over 1.6 million photographs from the Courtauld’s Conway, Laib, and Kersting collections, free for non-commercial use. Find out more about the project here.

Visions of London

by Hannah Wilson

Sir Christopher Wren’s plan of London. CON_B04591_F005_016. The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

Over the last few centuries, London has inspired architects to imagine how they would reshape the city to their own distinct styles.

After the fire of London in 1666, Sir Christopher Wren proposed a new street layout for London, with streets dividing building blocks into rectangles around St Paul’s Cathedral, and branching out from central points in the areas east and west. But, this plan was never carried out and the majority of the old irregular street layouts were maintained.

Since then, many architects have presented their visions of how they would alter the skyline, buildings and roads of London. Just like Wren’s vision, many of these designs were never built and now all that remains of these abandoned plans are the drawings the architects produced.

Many designs are preserved in the Conway Library of the Courtauld Institute, alongside collections of photographs and plans of buildings and monuments across the globe. The collection’s boxes containing Architectural Drawings by 20th-century British architects show great variation in their visions of a reshaped city with differing architectural inspirations: from the classical and romantic to the more futuristic.

***

The Strand today: Via Google Earth.

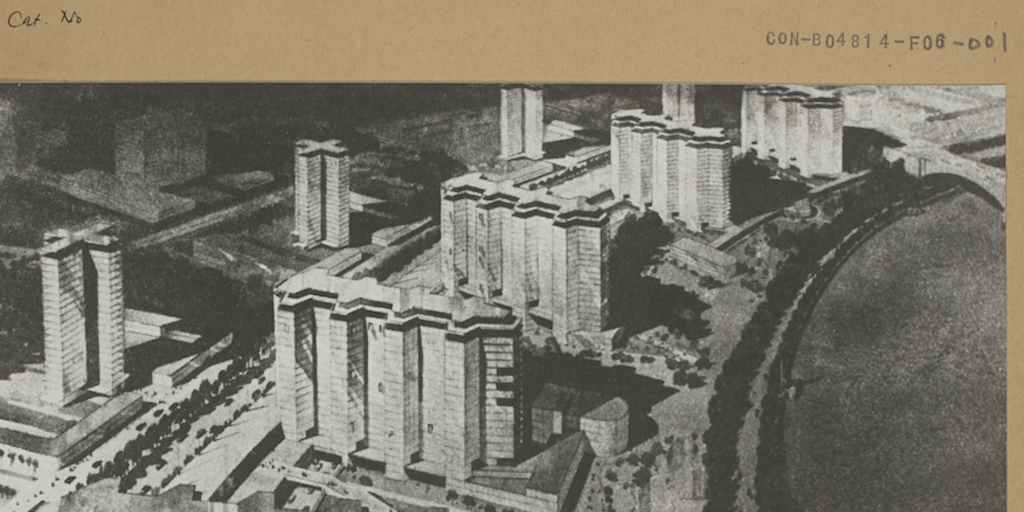

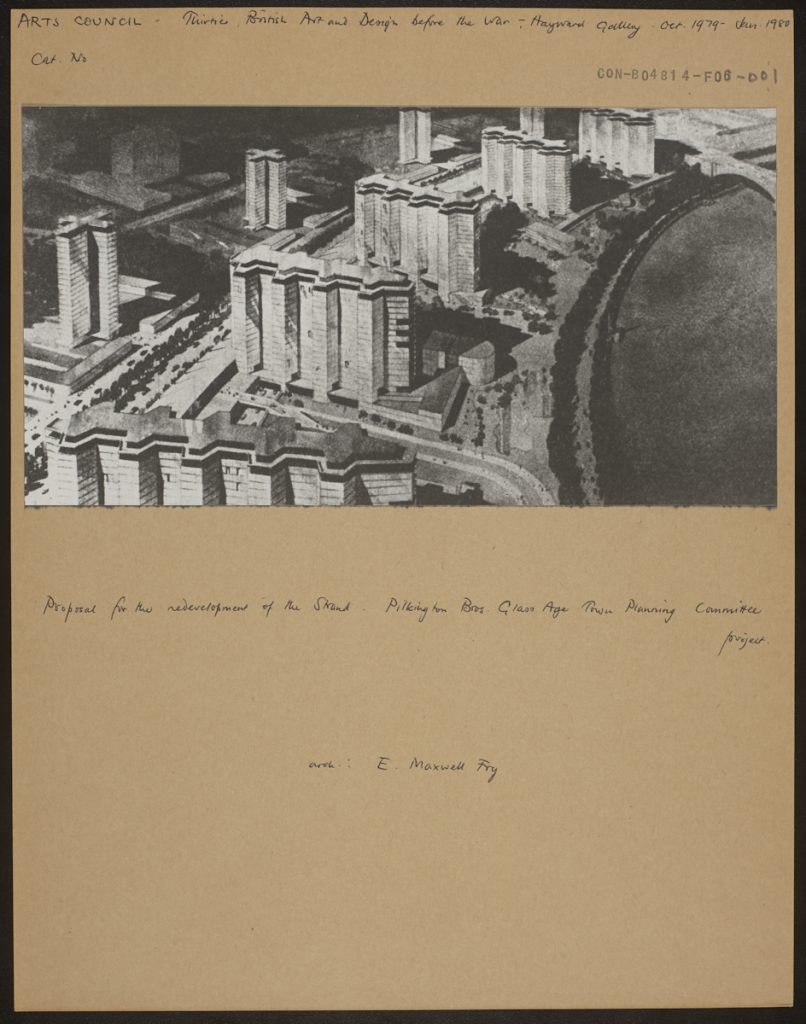

Just before the outbreak of the second World War, the Glass Age Town Planning Committee proposed their vision of a changed London with plans for rebuilding the entirety of Bond Street and the Strand.

Alongside a reimagined Bond Street by Howard Robertson, Maxwell Fry’s designs for the Strand formed part of the February 1939 issue of Architectural Review.

Luckily for the Courtauld Institute’s then-future move, Fry seems to have allowed Somerset House to remain intact in the upper right corner of his plan (the Courtauld would move into the building in 1989).

The large scale destruction of older buildings required for these plans to happen, and a lack of any form of planning permission are both factors which prevented these designs from becoming a reality. But the purpose of the Glass Age Town Planning Commitee was initially mainly to function as an advertising campaign by Pilkington Brothers Ltd., a glass production company.

The Glass Age Commitee sought both to promote their product as a building material and to present concepts of how buildings in the 21st century might look with further developments in technology and modern architectural styling. These designs could therefore be as radical and unrealistic as the architects wanted because they were so unlikely to ever be built. Yet, Fry’s proposal still presents an interesting insight into how architects in the 1930s may have thought architecture could develop and how they imagined a future London could look.

Design of the Strand, E Maxwell Fry. CON_B04814_F006_001. The Courtauld Institute of Art. CC-BY-NC.

The view of the Strand in 2020 is different to how the Glass Age Committee would have seen it in the 1930s, but it has arguably not changed as much as they would have expected. Tower blocks have yet to spring up in this area, although the redevelopments of Charing Cross station and the façade of Coutts’ bank later in the 20th century increased the amount of glass in their designs. And of course, the skyline of London from Waterloo Bridge – branching just off the Strand – is now dominated by glass skyscrapers, most prominently the Shard.

In some ways, then, the Glass Age Committee’s ambitions for greater use of glass in building came true, although not necessarily in the ways they had imagined.

Read Hannah Wilson’s full post, which includes more images of designs for other areas of London, including Bond Street, Hyde Park, and St Paul’s, on the Courtauld Connects Digitisation Project Blog.

great activity in the strand at present…

see Courtauld connect and Westminster council plans for redeveloping area around Somerset House

Yes indeed! There is a lot of activity going on especially around the Aldwych area as you say.

For anyone who is interested-

More on Courtauld Connects here: https://connects.courtauld.ac.uk/

And more on the Aldwych development proposals: https://strandaldwych.org/ (although all has gone a little quiet, something for Strandlines to investigate I think!