From the Electrophone to the Xbox Kinect: Remediating the Gaiety Girls

Posted in 19th Century, Strandlines and tagged with Bohemian Girl, Gaiety Girls, Gaiety Theatre

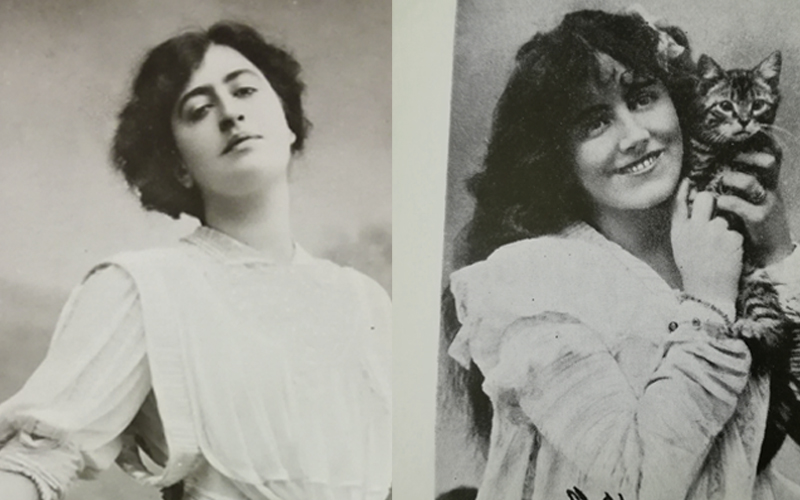

In my last post I described how the Strand’s Gaiety theatre became famous as the home of the Gaiety Girls. Under the stewardship of impresario George Edwardes the Girls changed the face of London’s theatre world while helping to lay the groundwork for modern celebrity culture. In this post I want to focus on two Gaiety Girls in particular: Constance Collier and Ellaline Terriss. Having made their Gaiety debuts in the mid-1890s, both carved out lengthy careers that saw them giving a face and form to shifting understandings of Britishness, modernity and femininity. During a time of rapid technological change they transcended the stage to engage audiences via a range of new media, from radio and records to film. It’s for this reason that we chose to explore their legacies for the Strandlines project Moving Past Present, which saw artist Janina Lange ‘reanimating’ them as digital avatars.

In the process of creating these CG doppelgangers we learned a lot about late-Victorian theatre, early cinema and the history of the Strand. We also got to know Collier and Terriss – or, at least, the public personas each constructed – pretty well. Their memoirs underline just how distinct their approaches to stardom were: Terriss begins hers by conceding ‘I was never a great actress… Great actresses play Lady Macbeth and Camille, and, I believe, cause audiences to swoon away’;[i] Collier, by contrast, portrays herself as a born thespian, revealing that ‘the first part I studied, when I was about ten or eleven years old, was Lady Macbeth’.[ii] Where Terriss’ sly modesty is entirely in keeping with her image as a paragon of feminine sweetness and forbearance (‘some years ago I christened myself “The Veteran Ingénue”… I was nearly fifty and still playing young parts’[iii]), Collier’s anecdote shows the flair for self-dramatization that served her well playing a succession of vamps, villainesses, fallen women and ‘exotic’ beauties.

The pair also reached the Gaiety by very different routes. Terriss’ father William was himself a beloved and successful performer who counted the likes of Ellen Terry and Herbert Beerbohm-Tree among his friends. When Edwardes coaxed Ellaline to the Gaiety, it was to play the eponymous Girl in shows like The Shop Girl, The Circus Girl and A Runaway Girl. Collier’s parents were also actors. They, however, had spent their careers scraping by in touring shows and regional pantomimes, and were less than thrilled when she announced her intention to follow in their footsteps. Collier, though, was determined, her dreams of fame and fortune fuelled by the glamour of the Nineteenth-century Strand (‘I loved the Law courts and the old Church in the Strand. I used to look at the Savoy Hotel and think of the luxury and splendor it contained, and vow that one day I would have a little of it too, for my mother and myself. I would stand outside the theatres, and wonder if I would ever act in them – the Gaiety, the Lyceum, Drury Lane, and the Haymarket’[i]). Harlequinade: The Story of My Life portrays her first encounter with Edwardes in suitably dramatic style: having quarreled with her father about his plan for her to become a nurse, Collier storms across Waterloo Bridge through the January rain ‘in a blind, white fury’, stopping at the stage door of the Gaiety and demanding to see ‘the guv’nor’. The doorkeeper is ‘amazed – it was like asking to see the Grand Lama of Thibet… If I had commanded the walls of Jericho to fall he could not have been more surprised.’[ii] Edwardes, however, happens to be passing and grants her an interview – and then a spot in the chorus. While her mother is initially unsure (‘the Gaiety theatre seemed a terrible place for her ewe lamb’[iii]), she is apparently won over by Edwardes’ charisma and his concern for his Girls’ wellbeing,[iv] and so Collier’s Gaiety career begins.

By now it shouldn’t be such a surprise to hear that where Terriss found the mask of comedy a better fit, Collier preferred melodrama and tragedy. She quickly abandoned musical comedy (‘I was too big and my voice was not good enough’) for the ‘legitimate theatre’, spurred on by the demise of a relationship with an older actor who dismisses her as ‘only a Gaiety Girl’ – a slight which reignites her ambition to match Mrs. Siddons in the ‘classic parts.’[v] There followed a lengthy career as a performer, writer and dialogue coach that saw her working with D.W. Griffith, Josef von Sternberg, Ivor Novello, Alfred Hitchcock and Katherine Hepburn, to name but a few; Terriss, meanwhile, found popular success alongside her husband Seymour Hicks, a comedian, actor, writer and producer. It was Terriss, though, who was thrust into the role of real-life tragic heroine when her father was murdered by an erstwhile protégée in 1897 while acting at the Adelphi. In the course of imagining how the murder might have been averted, she takes readers on a tour of the back streets of the Strand’s theatre district: ‘By one of those strange tricks of Fate, Seymour, passing along Henrietta Street to the Gaiety, must have been within a few yards of my father, who was going along Maiden Lane, which runs parallel and is the next street – to meet his death. Had they been together – who knows?’[vi]

Ethnicity, Identity and Empire

Collier in Egyptian, American, Grecian and Messalinian costume.

Often cast as a flower of English womanhood, Terriss was in fact born off the coast of Patagonia, after William and his wife migrated to the Malvinas/Falklands (colonized by Britain in 1840) to raise sheep. Collier, meanwhile, was born close to the royal seat of Windsor, though her ‘Mediterranean’ heritage (her mother was half Portuguese) meant she registered as ethnically ‘other’. At a time when English theatre was obsessed with ‘the Orient’ and with the fates of empires past and present, this meant she was often cast in ‘exotic’ roles – from Cleopatra, Pallas Athene, Poppea and Ben Hur’s Iris to the native American Adulola in 1907’s The Last of His Race and the bandit queen in Ivor Novello’s 1922 film of Balfe’s ballad opera The Bohemian Girl.

In Harlequinade Collier frequently accounts for aspects of her character through essentializing references to what she variously calls her ‘Latin’ or ‘Arab’ heritage – terms she uses interchangeably. Her claims that her ancestry has made her romantic, vain, impetuous and in need of ‘civilizing’ make for awkward reading today, but they also represent attempts to articulate a kind of hybrid identity in a cultural climate rife with xenophobia. Various episodes in Harlequinade suggest that, for Collier, her ‘foreignness’ was bound up with her sense of herself as a bohemian free spirit: the schoolmistress who makes her ‘plait my lovely, dark, curly hair that my mother was so proud of’[vii] comes to embody the kind of Victorian narrow-mindedness that she develops a creative, cosmopolitan identity in opposition to.

Terriss was more respectful of tradition and the establishment. Her memoirs record her many brushes with royalty (including the future Edward VII prompting her with the lyrics to her hit ‘A Little Bit of String’ when, star-struck at his having requested a private recital, she forgets them), and she became Lady Hicks when Seymour received a knighthood. Her stage performances often hinged on the novelty of seeing a coy young Englishwoman saying and doing incongruously saucy things (‘understanding nothing about them I used to sing quite innocently lines on the most controversial subjects and generally, I believe, looked the most surprised individual in the world when I heard boos or cheers’[viii]). A similar dynamic was at work in her renditions of songs and dances derived from African-American culture – minstrelsy being something of a Gaiety staple.

Antisemitic humour was another staple, though one review of The Shop Girl argued that the play showed ‘more daring than discretion in making fun, however, comically, of the Hebrews’ given how many of the Gaiety’s patrons were Jewish.[ix] Collier describes how enterprising Londoners who had made their fortunes in South African diamond mines, many of them Anglo-Jewish, returned to London to vie with blue-blooded ‘stage door Johnnies’ for the right to pay court to the Gaiety Girls. In doing so, she frames the cross-class romances embarked upon by ‘Johnnies’ like the 4th Marquess of Headfort (who, as I mentioned last time, married Gaiety Girl Rosie Boote) as antidotes to ‘the hypocrisy and prudery of the Victorian age’ – albeit while striking a queasily eugenicist note (‘it was as if Nature were fortifying herself and using the blood and strength of these magnificent plebeians to build a finer race’[x]).

From the Movies to Motion Capture

Illustration from Pastimes at Home and at School: A Practical Manual of Delsarte Exercises and Elocution, 1897; diagram from Microsoft’s patent application for the Kinect motion sensing interface, 2011.

Less troubling, but equally of their time, are Terriss’ references to new technologies like automobiles, helicopters and ‘electrophones’ (a kind of pre-radio broadcast technology which permitted users to listen live to concerts and plays by ‘holding earphones to your ears on a kind of two-pronged metal rod’[xi]). The Listeners In, a 1922 short film which sees Terriss and Hicks larking about with a wireless set only to tune in to a fellow radio user turning the air blue, sums up the Gaiety Girl attitude to the modern world: game, perhaps rather bemused, not unduly put out by a little naughtiness. Available to stream via British Pathé’s site, The Listeners In is one of the few fragments of Terriss/Collier footage available online – though at the time of writing a decidedly grainy transfer of The Bohemian Girl is also up on YouTube. The British Film Institute’s archives do, however, hold a range of other films in which they feature, ranging from a fascinating version of Dickens’ Bleak House in which Collier plays Lady Dedlock to a short in which Terriss, dressed in a painter’s smock and flanked by a chorus of similarly attired female dancers, a cuts a jig with a cigarette in her mouth.

In her screen performances Collier, considered the more accomplished actor in her day, often strikes poses that now seem hammily antiquated, rooted as they are in the influential nineteenth-century acting teacher François Delsartes’ system of ‘prescriptive, formulaic, ostentatious’ stock gestures.[xii] As philosopher Gilles Deleuze has argued, the advent of cinematic cutting and montage precipitated a move away from this regime of codified ‘figures and poses’, ‘changing the status of movement’ by ‘releas[ing] values which were not posed, not measured, which related movement to the any-instant-whatever’ and inspiring thinkers like Henri Bergson to advance new understandings of time itself.[xiii] Where Collier’s acting can now smack (to quote Bergson) of ‘something mechanical encrusted on the living’[xiv], Terriss’ skits and routines often look oddly contemporary, their playful spontaneity reminiscent of the viral dance crazes and comic GIFs swapped via social media today.

These performances provided inspiration for Moving Past Present. The project also drew on Janina’s previous work on the silent comedy star Sarah Duhamel, work that explores modes of performing gender in early film while addressing how, in Janina’s words, recording technologies ‘inscribe themselves in the very movements they are looking to reproduce’. Moving Past Present eventually assumed a form that was part exhibition (featuring memorabilia, from cigarette cards to sheet music, that we’d sourced from eBay), part performance, and part digital motion capture session. Using a Kinect gesture tracking device – a technology created as a means of controlling Xbox 360 games – physical theatre performer Meghan Tredway reproduced gestures and poses from performances by Terriss and Collier, which were in turn mimicked by the Ellaline and Constance avatars that Janina had constructed using 3D modeling software developed by Adobe. With the assistance of animator and motion capture engineer Moses Attah, Meghan’s movements were recorded and uploaded to the open source animation database Sketchfab. If you visit https://sketchfab.com/moving_past_present you can view Sketchfab’s crash test dummy-like avatars running through the movements we recorded – and indeed download the motion data for yourself.

We hoped that this juxtaposition of past and present would inspire guests to think about the terms on which different media technologies allow us to (re)fashion our identities and record our lives. Today, Terriss and Collier survive via oil paintings, magazine articles, cigarette cards, films and books. Some are housed in official archives like those of the BFI or the V&A, others circulate via eBay, Pinterest or YouTube; some are subject to legal restrictions, others are copyright-free. With motion capture comes the possibility of archiving not just someone’s words and stories, not just stills or moving images, but also individuals’ gestural idiosyncracies, their particular modes of inhabiting their bodies and occupying space. Converting live movement into 3D point cloud data, such devices open up new definitions of ‘life writing’. If nothing else, experimenting with the Kinect gave us a much deeper appreciation for Terriss and Collier’s accomplishments as performers: Meghan, herself no slouch in the dexterity stakes, was impressed by the degree of coordination, skill and fitness Terriss’s apparently effortless comic dances took. But if Meghan sometimes struggled to keep up with Terriss in rehearsals, the Kinect also struggled to keep up with her – even after Janina had taped white squares onto her trousers and shoes in order to help it recognize her knees and feet. By contrast, Collier’s exaggerated stock gestures, designed to be ‘readable’ from the other end of a theatre, proved easier for the (new-fangled but already obsolescent) device to parse.

This discovery underlines the irony that if new technologies – from touchscreens to voice recognition systems to augmented reality interfaces and infrared motion sensors – aim to make interacting with digital code more ‘natural’, they also encourage us to perform gestures, strike poses and pronounce words in ways that computers can understand. It reminds us that gesture has a history, that our movements, mannerisms and modes of relating to our bodies are shaped by the circumstances we find ourselves in, the media that surround us and the objects we live and work amongst. Sketchfab is bound up with gaming culture, which remains obsessed with macho displays of potency and prowess. As such, it’s full of files you can download if you want to create an avatar that can leap and kick and grab. Until Janina’s intervention, though, there weren’t many examples of the kind of mischievous athleticism Ellaline Terriss excelled at, or the sort of melodramatic intensity and campy hauteur that was Constance Collier’s specialty. Likewise, the avatar creation software Janina used is a powerful tool that doesn’t require a degree in computer science to use, but it also puts bizarre and frustrating limits on what’s possible: the weird, figure-hugging liquid metal leotards that our digital Constance and Ellaline are wearing, for example, are a consequence of Adobe’s default settings for rendering female avatars.

As this suggests, the digital afterlife can be a strange place, a place where bygone stars are rescued from obscurity only to be subjected to hitherto unimaginable indignities. While we can’t know what Terriss or Collier would make of their avatars, it would be nice to think that we’ve helped to bring their work to a (slightly) wider audience. If nothing else, Collier’s turn as Honoria Dedlock (in a film that radically reworks Bleak House’s structure to make her the protagonist) deserves to be more widely seen. And if that’s too much to ask, couldn’t we at least have a few more Bohemian Girl reaction GIFs in the world?

[i] Collier, Harlequinade, p.41

[ii] Collier, Harlequinade, pp.45-6

[iii] Collier, Harleqinade, p.46

[iv] As we heard last time, the myth of ‘Gaiety George’ and his was a potent one, though certain accounts paint a sleazier and more tyrannical picture…

[v] Harlequinade, pp.64-5

[vi] Ellaline Terriss (1955). Just a Little Bit of String. London: Hutchinson and Company, p.145

[vii] Collier, Harlequinade, p.26

[viii] Terriss, Herself, p.73

[ix] The Sketch, 22 July 1896, p.542

[x] Collier, Harlequinade, p.48

[xi] Terriss, String, p.118

[xii] Anthony Paraskeva, The Speech-Gesture Complex: Modernism, Theatre, Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, p.28

[xiii] Gilles Deleuze (2013 [1983]). Cinema I: The Movement-Image. London: Bloomsbury, p.7.

[xiv] Henri Bergson (1956). ‘Laughter.’ Comedy. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, p.84

[i] Ellaline Terriss (1928). Ellaline Terriss by Herself and with Others. London: Cassell, p.4

[ii] Constance Collier (1929). Harlequinade: The Story of my Life. London: John Lane, p.32

[iii] Terriss, Herself, p.3