Lord Nelson and the Strand

Posted in contemporary, Strandlines and tagged with Nelson

On a bright, cold afternoon at the end of January 2003 I made my way down the Strand towards Trafalgar Square in the company of American audio artist and playwright Gregory Whitehead and BBC radio producer Neil McCarthy. Ahead of us, high up on the column in Trafalgar Square and silhouetted against a clear blue wintry sky, was Lord Nelson. In my handbag was a single strand of his hair.

Well, not so much a strand, more a split end – the wisp was so tiny it was barely visible to the naked eye – bought by Gregory, on eBay, for $52.50. We were heading for a collectors’ shop half-way down the Strand where we leafed through files of plastic pockets containing hair from the heads of the famous and the long dead: Charles Dickens, Abraham Lincoln, John F. Kennedy, and Marilyn Monroe. Together we were making a programme for Radio 4 in which we were exploring the authenticity of our relic, and contemplating our responsibilities in being in possession of it. ((On One Lost Hair, BBC Radio 4, May 10, 2004. The title of the programme is an anagram of Horatio Nelson.))

Earlier in the day we had presented our strand to Nelson scholar Colin White. He told us that, as the hero lay dying from a fatal gunshot wound during the Battle of Trafalgar, on 21st October 1805, ‘one of… [his final instructions] was: “Pray let my dear Lady Hamilton [Nelson’s lover] have all my hair and everything belonging to me.’ He added that,

‘It is quite clear that [Nelson’s flag captain] Hardy kept some for himself, but most of the hair went to Emma [Hamilton], including the biggest piece of all which is Nelson’s pigtail. That pigtail passed into the hands of Horatia Nelson, the daughter of Nelson and Emma…[who] would respond to requests from people asking for a relic of her father.’((Colin White, cited in Gregory Whitehead, “On One Last Hair,” Cabinet magazine, issue 16: “The Sea,” Winter 2004/05, http://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/16/whitehead.php (accessed January 10, 2016).))

When Horatia died in 1881, her children donated the pigtail to the Greenwich Hospital, and as part of that collection it would contribute to ‘the nucleus of the new museum in 1934’, now the National Maritime Museum.((John Munday, “The Nelson Relics,” in Colin White, The Nelson Companion (London: Quadrillion Publishing, 1997), 65, 77.)) Today, the pigtail may be found occupying a significant place in the Museum’s Nelson, Navy, Nation gallery (opened in 2013), in one of two large display cases in a section dedicated to “a hero mourned”: http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/63223.html

Displayed with the pigtail is a mourning ring commemorating Nelson – one of at least 50 made following his death, for family and associates, by a jeweller named John Salter who had premises at no. 35 Strand, on the south side between Villiers Street and Buckingham Street, from 1802 to 1825.((“John Salter (biographical details),” British Museum website, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=191281 (accessed March 17, 2016).))

http://mapco.net/wallis1804/wallis14.htm

A trade card from the period in the British Museum advertises, ‘John Salter, Successor to Mr. Joseph Greensill: Working Jeweller, Silversmith, & Sword Cutler, 35 Strand, London, Great Variety of Sheffield Plate with Silver Edges, Diamonds, & Pearls, Gold & Silver Lace &c. Bought. Epulets, Sashes, Sword Knotts & Accoutrements. Engraving Neatly Executed’.((See: “Trade card/print,” “Collection online”, Museum number D,2.98, British Museum website, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3043177&partId=1 (accessed April 6, 2016). The card, from the collection of Sarah Sophia Banks, has ‘1806’ (the year of Nelson’s funeral) written in ink in the lower right hand corner. The words ‘Silvester SC. 27 Strand’ also appear in the lower centre of the design, presumably advertising the name and address of the printer.))

http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=3043177&partId=1

The rings, which must have been sold (and perhaps produced) at Salter’s premises at 35 Strand, are made from gold with the bezel enameled with the letters “N” and “B” surmounted by two coronets above the word “TRAFALGAR”. Inside the bezel is the inscription, ‘lost to his country 21 Octr 1805 aged 47’, and the inner hoop of the ring bears the words “PALMAM QUI MERUIT FERAT” (“let he who merits the palm possess it”)((“Mourning ring,” JEW0167, National Maritime Museum website, http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/36318.html (accessed April 13, 2014).)) : the motto included in Nelson’s arms when he was made Baron Nelson of the Nile following victory over the French, at the Battle of the Nile on 1st August 1798((See: Nicholas Harris Nicolas, The Dispatches and Letters of Vice Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson, Vol. 3 (London: Henry Colburn, 1845), 79-81.))

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/36318.html

Many of Salter’s rings survive in public and private collections, but the one on display at the National Maritime Museum is distinguished by including a hinged bezel, which opens to reveal a glazed panel containing hair.((The National Maritime Museum has three of the Salter rings, two of which are in storage. The ring on display is the only one described as containing hair; its provenance is given as ‘Thomas Nelson’ suggesting it belonged to the 2nd Earl Nelson of Trafalgar and Merton (1786-1835) – the son of Lord Nelson’s sister Susannah Bolton – who inherited the title from William Nelson (1757-1835). See: ‘Mourning ring,’ Object ID))

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/36318.html

Nelson himself placed a high value on hair: as both a token of love and kinship, and as a material for commemoration. He is known to have owned a locket with a miniature portrait of Emma on one side and a lock of her hair on the other, which, we are told, ‘he habitually wore.’((The locket is in the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth. See: Munday, in The Nelson Companion, 77-78.)) When he received a lock of the infant Horatia’s hair sent by Emma while he was at sea on board the Victory, he replied, ‘You have sent me in that lock of beautiful hair a far richer present than any monarch in Europe could if he were so inclined’.((Tom Pocock, Horatio Nelson (London: Pimlico, 1994), 299.)) Following the death of the twenty-three year old Captain Edward Parker – an aide-de-campe whom Nelson regarded as a “son”, who died of complications following the amputation of a leg shattered by shot during a failed attempt on the French at Boulogne((Martyn Downer, “Lost Face of Nelson’s ‘Son’,” Martyn Downer Works of Art website, http://www.martyndowner.com/sale-highlights/lost-face-of-nelsons-son/ (accessed June 15, 2016).)) – he afterwards ‘kept a lock of “dear Parker’s hair”’, which, he said, ‘I value more than if he had left me a bulse of diamonds’.((Pocock, Horatio Nelson, 256. A bulse is a term for a ‘purse or bag in which to carry or measure valuables (such as diamonds or gold dust)’. See: “bulse,” Merriam-Webster website, http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/bulse (accessed June 15, 2016).))

Nelson was a regular visitor to the Strand and the surrounding area when on shore in London. He made visits to John Salter’s premises, which, according to John May, was ‘much patronized’ by him, and ‘from whom he bought a number of personal items, including…a silver gilt cup’ for Horatia, which is now in the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth.((John May, “Nelson Commemorated,” in White, The Nelson Companion, 91.)) ‘As a young officer he…[took] lodgings’ in Salisbury Street south of the Strand, ‘to be near both the Navy Office [in the South Wing of Somerset House] and the Admiralty’((Tom Pocock, “In Nelson’s Footprints,” in White, The Nelson Companion, 110.)): to which he reported throughout his adult life. In recognition of his connection with Somerset House, the great spiralling staircase that he would have used for access to attend meetings in the Navy Boardroom, referred to in the eighteenth century as the Navy Staircase, has long since been known as the Nelson Staircase.

https://invisiblecitiesphoto.wordpress.com/2012/11/25/nelson-stair/

Spotting him on the Strand in 1805, Benjamin Silliman (1779-1864) (the American chemist) described seeing him, ‘walking in company with his chaplain and, as usual, followed by a crowd’. He added, ‘Lord Nelson cannot appear in the streets without immediately collecting a retinue, which augments as he proceeds, and when he enters a shop the door is thronged until he comes out, when the air rings with huzzas and the dark cloud of the populace again moves on and hangs upon his skirts.’((Pocock, Horatio Nelson, 309.))

Nelson’s final appearance in the Strand was on 9th January 1806 when his body was taken from Admiralty House, where it had lain overnight, for interment in a majestic porphyry tomb (originally intended for Cardinal Wolsey) in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

http://www.explore-stpauls.net/oct03/textMM/NelsonTombN.htm

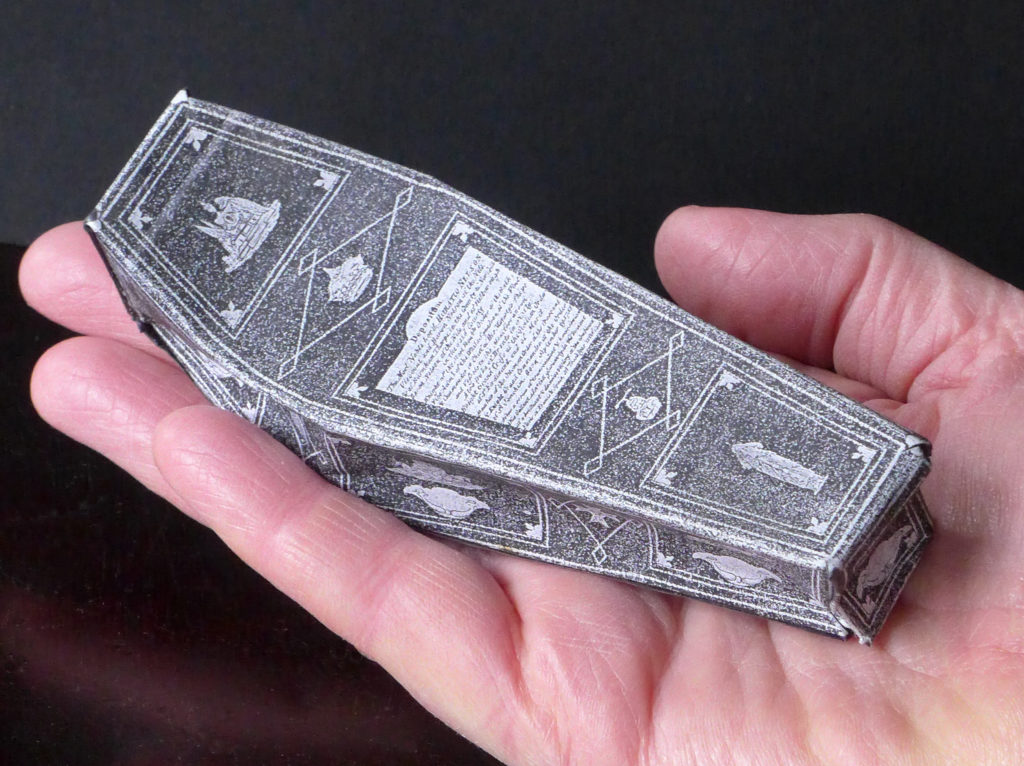

Encased in three coffins, the first made of wood from the mainmast of the French ship l’Orient (destroyed at the Battle of the Nile((Pocock, Horatio Nelson, 339.)); the second of lead, and the third magnificently decorated with designs by the Ackerman brothers – including his ‘coat of arms, the stars of his orders of chivalry, seahorses – and …a crocodile to represent the Battle of the Nile’((White, in The Nelson Companion, 9.)) – http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/136664.html

the hero’s remains were conveyed on ‘a huge, plumed, funeral car’1

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/136657.html

that ‘[moved] in solemn pace, through the Strand to Temple Bar gate’((The Gentleman’s Magazine (1806), Vol. LXXVI: 69.)), ‘accompanied…by friends who remembered him there’ together with some thirty-one admirals, a hundred captains,2 ‘forty-eight seamen and Royal Marines from HMS Victory’((White, in The Nelson Companion, 10.)) and a vast crowd of onlookers stationed at every vantage point along the way.

But in place of the huzzahs that rang out to greet Nelson on the Strand the previous year, the crowd on this solemn occasion produced, ‘a ruffling sound [that] ran ahead of [the funeral car] as the men watching from the pavement, windows and rooftops, bared their heads’((Pocock, Horatio Nelson, 340.)) – doffing their hats and creating a noise described by one witness as being ‘like the sound of waves on the seashore’.((White, in The Nelson Companion, 12.))

http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/71082.html

Inspired by the idea of the seashore – and of burial at sea – almost 200 years later we took our little wisp of Nelson’s hair, sealed in a tiny bottle and balanced in a miniature cardboard replica of the Ackermann brothers’ decorated coffin, down to the strand at Greenwich. As the Thames lapped our feet we launched our little strand of Nelson’s hair on a fast-flowing outgoing tide towards France – and towards Emma Hamilton, who died and was buried in Calais in January 1815.

© Jane Wildgoose | June 2016