Ford Madox Ford on the Strand in the nineteenth century

Posted in 1910-1919, Animal, Strands, streets and roads, theatres and tagged with Beau Brummel, Ford Maddox Ford, animals, autobiography

The Strand figures twice in Ford Madox Ford’s reminiscences about his pre-Raphaelite relations, Ancient Lights (London: Chapman and Hall, 1911). First in this passage which is revealing about the different experiences of place in different generations:

I was talking the other day to a woman of position when she told me that her daughters were immeasurably freer than she had been at their age. I asked her if she would let her daughters walk about alone in the streets. “Oh dear yes,” she said. I asked her whether she would allow one of them to walk down Bond Street alone. “Oh dear, certainly not Bond Street!” she said. I tried to get at what was the matter with Bond Street. I have walked down it myself innumerable times without noticing anything to distinguish it from any other street. But she said no, the girl might walk about Sloane Street or that sort of place, but certainly not Bond Street. I should have thought myself, from observation, that Sloane Street was rather the haunt of evil characters, but I let the matter drop when my friend observed that, of course, a man of my intelligence must be only laughing when I pretended that I could not see the distinction. I pursued therefore further geographical investigations. I asked her if she would permit her daughter to walk along the Strand. She said, “Good gracious me! The Strand! Why, I don’t suppose the child knows where it is!” I said, “But the Strand!” “My dear man,” she answered, “what should she want to walk along the Strand for? What could possibly take her to the Strand?” I suggested timidly, theatres. “But you only go to them in a brougham, muffled up to the eyes. She wouldn’t see which way she was going.” And she called to her daughter, who was on the other side of the room: ” My dear, do you know where the Strand is?” And in clear, well-drilled tones she got her answer, ” No, mamma,” as if a private were answering an officer. The young lady was certainly twenty-five. So that perhaps the old order does not so much change. Reflecting upon the subject of Bond Street, it occurred to me that it would not be so much a question of the maiden’s running the risk of encountering evil characters as that since every one walks down Bond Street, every one would see her walking there alone. You have got to make the concession to modern opinion, you have got to let your daughter go out without an attendant maid, but you do not want to let anybody know that you have done it.

(pp. 266-7)

The other passage describes a wonderfully surreal social encounter:

I had a very elderly and esteemed relative who once told me that whilst walking along the Strand he met a lion that had escaped from Exeter Change. I said, “What did you do?” and he looked at me with contempt as if the question were imbecile. “Do!” he said. “Why, I took a cab.” I imagine that still in most of the emergencies of this life we fly to that refuge.

In the period Ford is recalling, the cab would have been drawn by a horse; perhaps not the best thing to be tied behind with a lion in your path. . . Ford continues:

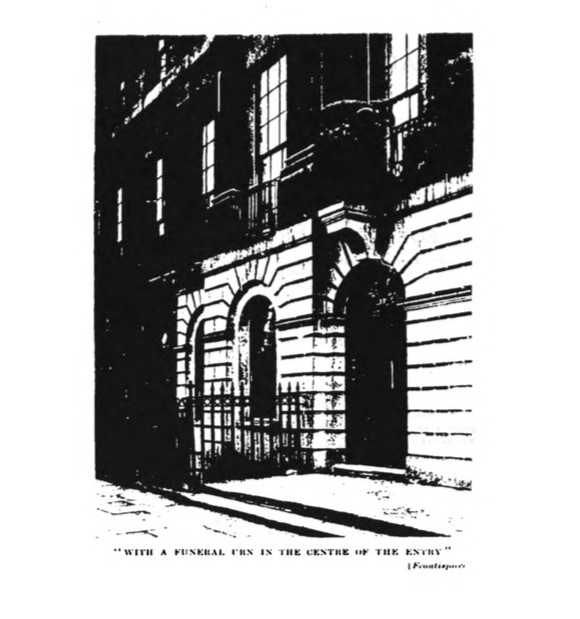

But I believe that the poor Strand has changed in another respect. I was once walking along the south side — the side on which now stand the Cecil and Strand Hotels — when my grandfather happened to drive past in a hansom, sprang suddenly out, and addressing me with many expletives and a look of alarm, wanted to know what the devil I was doing on that side. I really did not know why I should not be there or how it differed from the north side, but he concluded by saying that if he ever saw me there again he would kick me straightway out of his house. So I suppose that in the days of Beau Brummel there must have been unsavoury characters in that now rigid thoroughfare. But I doubt whether to-day we have so much sense of locality left. One street is becoming so much like another, and Booksellers’ Row is gone. I fancy that these actual changes in the aspect of the city must make a difference in our psychologies. You cannot be quite the same man if daily you joggle past St. Mary Abbott’s Terrace upon the top of a horse ‘bus: you cannot be the same man if you shoot past the terra-cotta plate-glass erections that have replaced those gracious, old houses with the triangle of unoccupied space in front of them — if you shoot, rattle and bang past them. Your thoughts must be different, and with each successive blow upon the observation your brain must change a little and a little more.

(pp. 267-8)

Also see the strand on Exeter ‘Change.